I have figured it out, dear reader!

In the foreground of the above image is the mizu-gumo device as used by shinobi of the Koka school, while behind it is an authentic device of the Iga shinobi. Having tested both extensively, I can confirm that they support the weight of an adult human and allow one to float across water in comfort. The mystery is solved!

What? Well, yes, in fairness it does look an awful lot like a modern pool floatie, and yes, it does bear only the most tenuous relation to the mizu-gumo as described in the ‘ninja manual’ Bansen shūkai.

You might, of course, object that it’s a little dubious to mostly ignore the BSSK, invent your own modern flotation device, and give your audience the impression that your modern interpretation is an authentic shinobi tool. Nobody would ever do that, right?

Making It Work, Ninja-Style

You may recall that in the previous post a couple of weeks ago, I argued two main points about the mizu-gumo device:

#1 - nobody really knows how it might have worked; and, more importantly,

#2 - we have no real reason to believe it was ever used in the first place.

These two points notwithstanding, ‘ninja’ historians have gone to considerable lengths over the years to try to find a way in which the mizu-gumo might be made to work. It’s fairly obvious what’s at stake here, I think - since the contents of the BSSK are an important foundational element in the postwar ‘ninja’ myth, anything that suggests BSSK might not be an entirely reliable source is going to be a problem. When Adam Savage on Mythbusters tried the mizu-gumo and kept on falling into the water, that made shinobi lore look kind of stupid. And we can’t have that, can we?

So here’s my main point for today: if you have access to the original BSSK and have read it, as I have, it quickly becomes apparent that a lot of the efforts to ‘make it work’ (as Tim Gunn might say) involve heavily modifying or even completely ignoring what BSSK actually says, often to the point where we’re really not dealing with the same device any more.

You see, I don’t think you can have it both ways. If the BSSK is indeed authentic shinobi lore, then the devices depicted therein should be usable pretty much as described. If, though, you have to mostly disregard the design in BSSK to get it to work (as appears to be the case), that calls into question how authentic and useful BSSK really is as a window onto actual shinobi practice.

I’d also have to say that at least some of the presentations of the mizu-gumo device to popular audiences are bordering on deceptive. If you’re not transparent about what you’re doing - if you present your heavily modified modern version of the mizu-gumo without acknowledging the changes, as if your version is an authentic shinobi tool as described in the BSSK - then you are almost certainly going to mislead your audience. After all, your viewers are hardly going to dig up a copy of the BSSK and check for themselves, even in Japan - they’re going to trust that you’re accurately representing what appears in the historical primary sources.

Through Thick and Thin

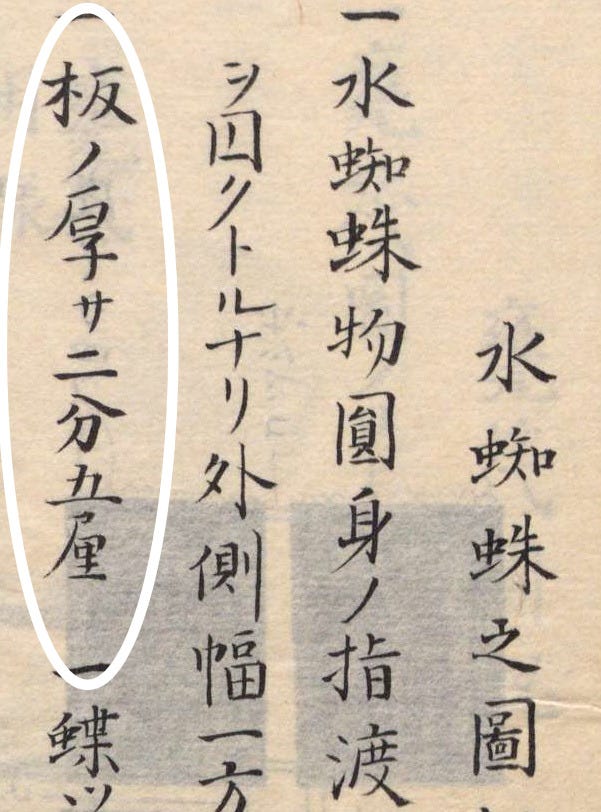

So let’s go to the original source and look the specifications for the mizu-gumo as it appears in BSSK. The specs are surprisingly detailed, including precise measurements for almost all of the components. Particularly relevant here is the thickness of the boards that are to be used in making up the mizu-gumo, which, per BSSK specifications, are supposed to be a thickness of two bu five rin:

As you can see if you can read Japanese, the BSSK text reads: “the thickness of the boards is two bu five rin (板ノ厚サ二分五厘, ita no atsusa nibu gorin).” Bu and rin are old Japanese units of measurement that were used until roughly the early 20th century, when the metric system became established in Japan. Anyway, two bu five rin converted to modern units would be around 7.9 mm, or for those of you who play in imperial, around a third of an inch.

That’s very thin! So thin, in fact, I was kind of shocked and had to double-check it, but the math is correct. For reference, 7.9 mm or 0.3” is about the thickness of my little finger or a medium-size slice of bread.

If you’re thinking that a piece of wood a third of an inch thick wouldn’t offer much buoyancy, well, that thought had occurred to me also. The next thought was to consider just how thick the mizu-gumo would have to be to be able to float. I have no real background in mathematics or physics, but fortunately, I found someone who does:

The above has no English translation or subtitles, unfortunately, but it’s basically an attempt to calculate how thick the mizu-gumo would have to be in order to allow a shinobi using one to float on water. Interestingly, the calculations are done both for the ‘walking on water’ version, where the mizu-gumo is worn in pairs on the feet, and for the ‘pool floatie’ option, where a single version is worn around the waist to provide buoyancy. The latter, you may recall, is what ‘ninja’ ‘historian’ Anthony Cummins insists the mizu-gumo actually was, to the point of rendering the device as “The water spider floating seat” in the published English translation of BSSK, even though the words “floating seat” don’t appear in the original text.1

The results of the calculations, done using the body weight of one of the participants in the video, can be seen at 8:59 and 9:26 above, but I’ll reproduce them here:

If standing (‘walking on water’), the mizu-gumo would need to have a thickness of 39 cm (15.3 inches).

If worn around the waist (‘pool floatie’), the mizu-gumo would need to have a thickness of 42 cm (16.5 inches).

What this means is that, to be usable, the mizu-gumo would have had to be between 52 and 56 times thicker than the design specs in BSSK. As one of the dudes in the video above remarks, that’s “pretty chunky” (bu-atsui).2

Now, I will admit I do not have the background to check these calculations and would welcome correction if they are erroneous. Assuming they are even roughly in the ballpark, though, I think we’re on fairly firm ground in stating the following:

The mizu-gumo as depicted in Bansen shūkai could not have worked, either as water-shoes or as a pool-floatie.

Note the key qualifier “as depicted in BSSK.” As we’ll see below, it’s not particularly hard to build a version of the mizu-gumo that more or less works - if you just ignore what BSSK says.

It’s a Simple Question of Weight Ratios

Here’s an example of what I’m talking about, an image that can be found at Wikininja, which apparently “contains information on all aspects of the historical ninja”:

The accompanying caption describes the mizu-gumo as:

a device that comes from the Bansenshukai (萬川集海) shinobi manual. Underneath the device are wooden flippers that allow a shinobi to crawl through water easily even without oars.

I realize I’m probably beating a dead horse here, but - nope. The device depicted is not what BSSK specifies, as we have just seen. Nor does BSSK specifically say that it’s meant to be used with flippers. What we have here is a series of post-war guesses and/or major modifications, not authentic shinobi knowledge.

Or, for another variation, consider this clip, apparently from what looks like a pretty fun event at the Iga Ninja Museum. I don’t know what the mizu-gumo being used here are made of - some kind of synthetic foam, perhaps - but the design is a thick, flat disk, not the hinged and flexible slats shown in the BSSK.

So a solid disk made of modern synthetic foam and 9” thick rather than 0.3”, but other than that, exactly as specified in the ancient ‘ninja manual’!

Still Waters Run Deep

I suspect that on some level most serious historians of the ‘ninja’ realize that they’ve got a problem in the shape of the mizu-gumo. The devices shown in the two examples above, at Wikininja and the Iga museum, probably would sort of work for floating across a body of water, but that’s not the point. The question is not, “Can you devise a contraption for floating on water using modern materials?”, because of course you can. The question is, “Would the device depicted in the so-called ‘ninja bible’ actually work?”, and the currently available historical, physical, and mathematical evidence suggests the answer is almost certainly “no.”

As we’ve seen, many people in both pop media and ‘ninja’ publications have had to work really hard to either fundamentally modify the BSSK design or to come up with explanations for how the mizu-gumo could maybe, perhaps, in ideal conditions have worked. A far simpler hypothesis, and one that would save everyone a ton of effort, is that the mizu-gumo never existed outside of the pages of BSSK.

This, though, is a possibility that ‘ninja’ history tries very hard to keep out of the mizu-gumo discourse, and I think with good reason. Once the ‘ninja’ historian starts to critically examine his sources and consider that they might not be what they appear to be - you know, do actual history - whole swathes of the field’s epistemological foundations begin to crumble. This is probably why Cummins, for one, was moved to describe the ‘water-shoes’ hypothesis for the mizu-gumo as “damaging.”3 You see, the ‘water-shoes’ interpretation is obviously wrong, and in being obviously wrong, it suggests two things:

(a) quite a few ‘ninja’ historians don’t actually know what they are talking about;

(b) BSSK and its related texts contain sections of fanciful bullshit that bear no relation to historical shinobi activity.

That is a door that most ‘ninja’ historians really, really don’t want to open, hence all the various attempts to make the mizu-gumo work. As I’d argue, though, ‘making it work’ ends up having the opposite effect, of demonstrating just how detached the BSSK design actually is from reality.

My take on the BSSK and other ‘ninja manuals’ (of which there are loads) is pretty simple. I think they’re far better understood as evidence of what people from the 17th century onward thought the shinobi might have done, not what they actually did. I think the Iga and Koka ones in particular were compiled as a way of imagining a distinct regional identity and military history, no matter how fictional that history might be. Their pages may contain some actual shinobi lore, but that is most likely buried under pages and pages of misremembered, half-digested, second-hand stuff the authors picked up from some old guy in the pub, plus a good measure of outright fantasy. Add to that abundant copying from many, many other sources, some of which had no connection to the shinobi at all, and you end up with a range of texts that no responsible historian should present to the public without very careful qualification.

What English-language readers actually get, of course, are ludicrous claims like this:

[A]s a survival and guerilla warfare manual, [BSSK] allows a single human to train diligently to become a clandestine operative with knowledge that rivals modern Special Forces, and the skills it teaches, if adapted, can have relevance for modern espionage and clandestine warfare even today.4

This is total, unmitigated horseshit, but unfortunately not particularly out of line with the character of English-language ‘ninja’ writing in general.

Anyway. I think I’m done with the ‘ninja manuals’ for now, as we’ve made the main points we need to on the topic. For next time, then, I’d like to change topics once more, and consider one of the most famous ‘ninja’ stories of all. This is the death of the warlord Uesugi Kenshin, supposedly killed in 1578 by a dwarf ‘ninja’ who hid in his toilet and stabbed him in the butt from down below.

(No, I’m not making this up. I promise.)

Minami, trans., The Book of Ninja, p. 328.

Japanese: ぶ厚い. This is without even considering the question of practicality. A mizu-gumo big enough to float would be very bulky and, depending on the wood used, probably quite heavy too (it’s four 15-inch chunks of solid wood, after all). This doesn’t seem like the kind of device you could carry around with you, especially if you have to carry two of them. In most situations you’d probably be better off swimming.

Minami, trans., The Book of Ninja, p. 328.

Cummins, intro to Minami, trans., The Book of Ninja, p. xxii.