Last time around we saw that Bansen shūkai, a late 17th century text sometimes referred to as the ‘ninja bible,’ contains quite a few sections that are strikingly similar to the late Ming Chinese military manual Military Preparedness (Wubei zhi, 1628), and noted that this calls into question how uniquely ‘ninja’ some of the stuff in the BSSK actually is. As it happens Military Preparedness isn’t the only contemporary military text from which the compiler of BSSK, Fujibayashi Yasutake, appears to have copied some of his stuff. There’s also evidence of lifting from a slightly earlier Japanese-produced military manual entitled The Ways of War: A Compendium for Warrior Service (Gunpō jiyōshū, c. 1653; hereafter ‘Warrior Service’).1 As far as I can tell, the text of BSSK itself does not acknowledge Warrior Service as the source, which in modern terms would make this plagiarism, but the rules were a bit different in 17th century Japan.

The similarities between the two texts have been known for a while - Cummins acknowledges them briefly in his notes and commentary to Minami’s translation of Bansen shūkai - but they’ve recently been discussed at greater length in a 2023 book chapter by the Japanese scholar Fukushima Takahito of Mie University, so the first half of the below is based largely on Fukushima’s discussion.2

Let No-One Else’s Work Evade Your Eyes

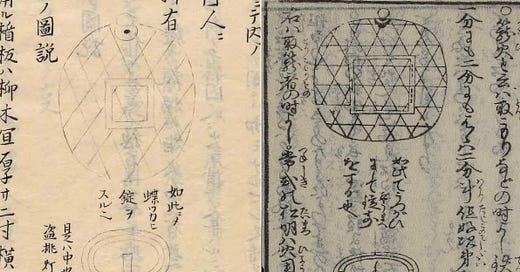

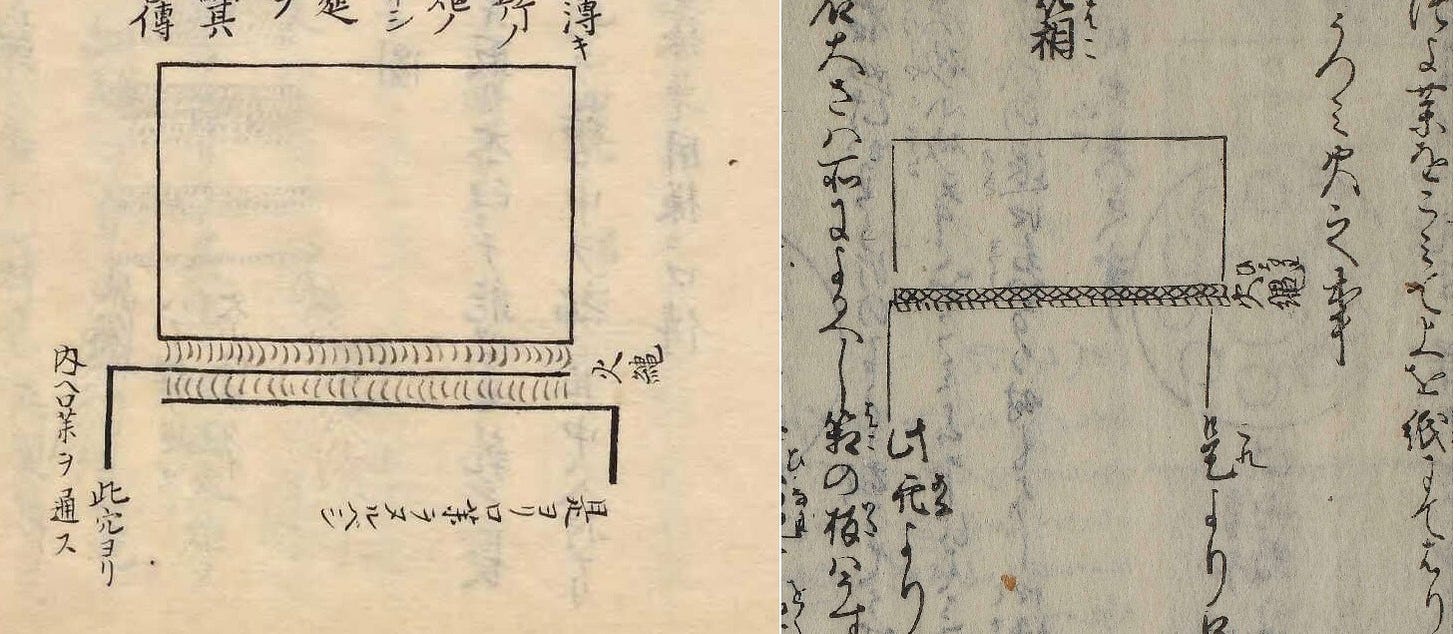

Let’s take a quick side-by-side look at BSSK and Warrior Service, as we did in the last post. The first example is a design for what is basically a hand grenade:

Pretty similar. Now, the chapters of Warrior Service we’re looking at are specifically about the tools and techniques of the shinobi, so you might object that perhaps this grenade design was one that was commonly used among shinobi in general and the similarities of design reflect that. After all, swords, spears, and bows are pretty much the same everywhere, so the same design could well recur across texts that had nothing to do with one another.

That’s a fair objection, except that the written text describing the objects is pretty much identical in both BSSK and Warrior Service:

(Warrior Service) On the Hand Grenade: During a night attack, one throws this into any location where the enemy is gathered, so as to cause panic.

(BSSK) During night attacks, one throws this where one sees the enemy is gathering, to strike at them and cause panic.3

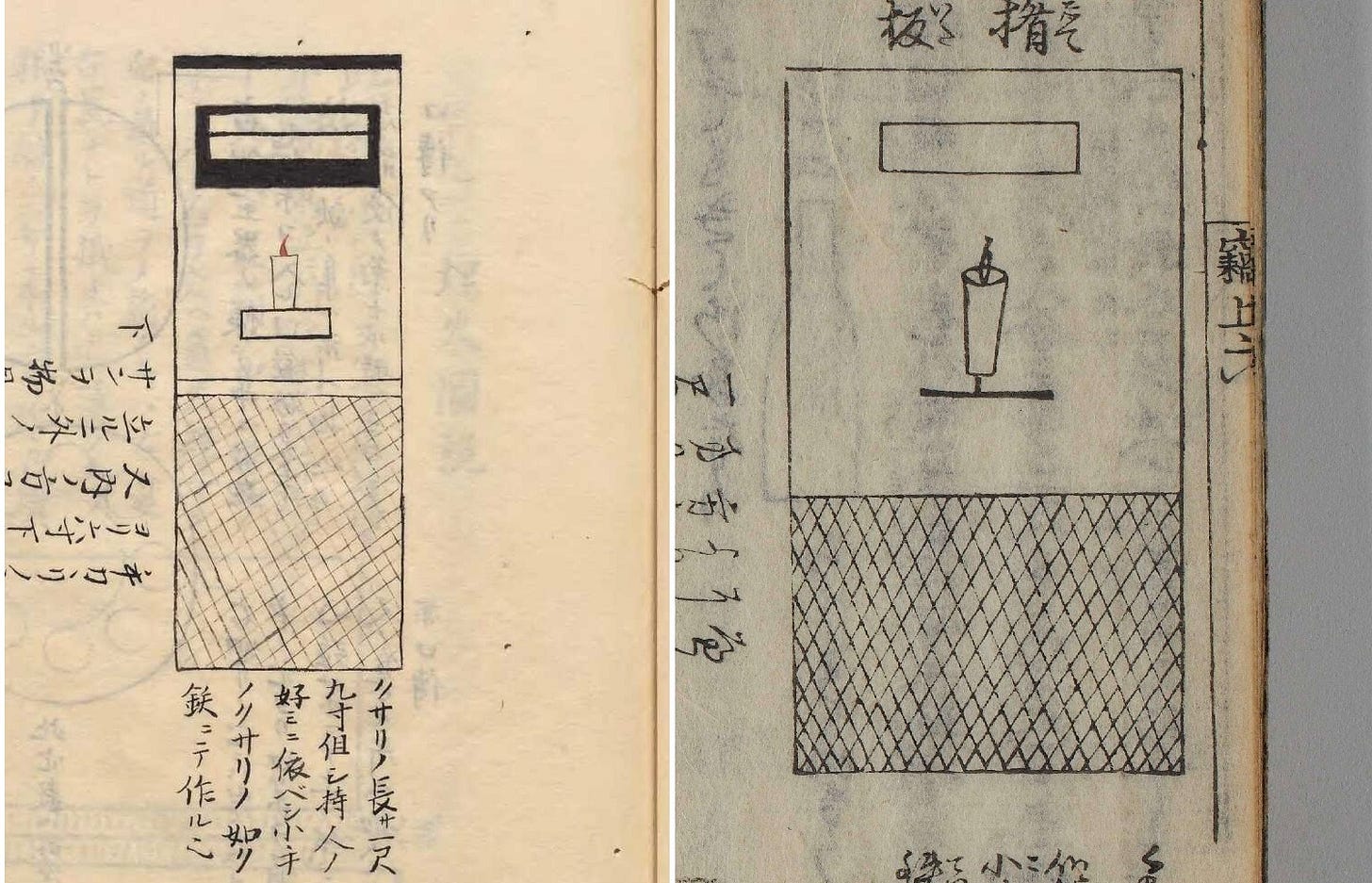

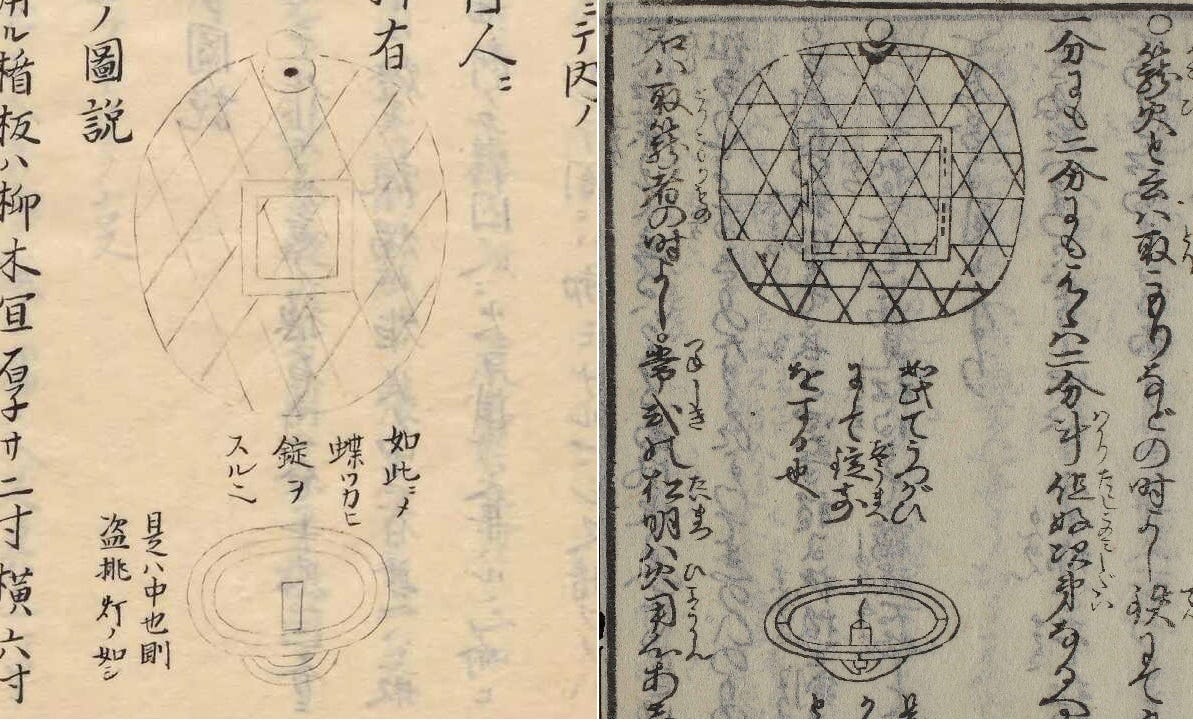

And as was true with the Ming Chinese manual Military Preparedness, it’s not just one device; there are enough identical illustrations and passages that copying really is the only explanation. The below, for instance, is a type of shielded candle supposed to be used in night attacks. It reminds me a bit of a modern SWAT team shield, though the cross-hatched bit at the bottom is supposed to be chain mail, which…would probably be pretty noisy, wouldn’t it?

This is a metal-weave shielded lantern, to be used in infiltration operations:

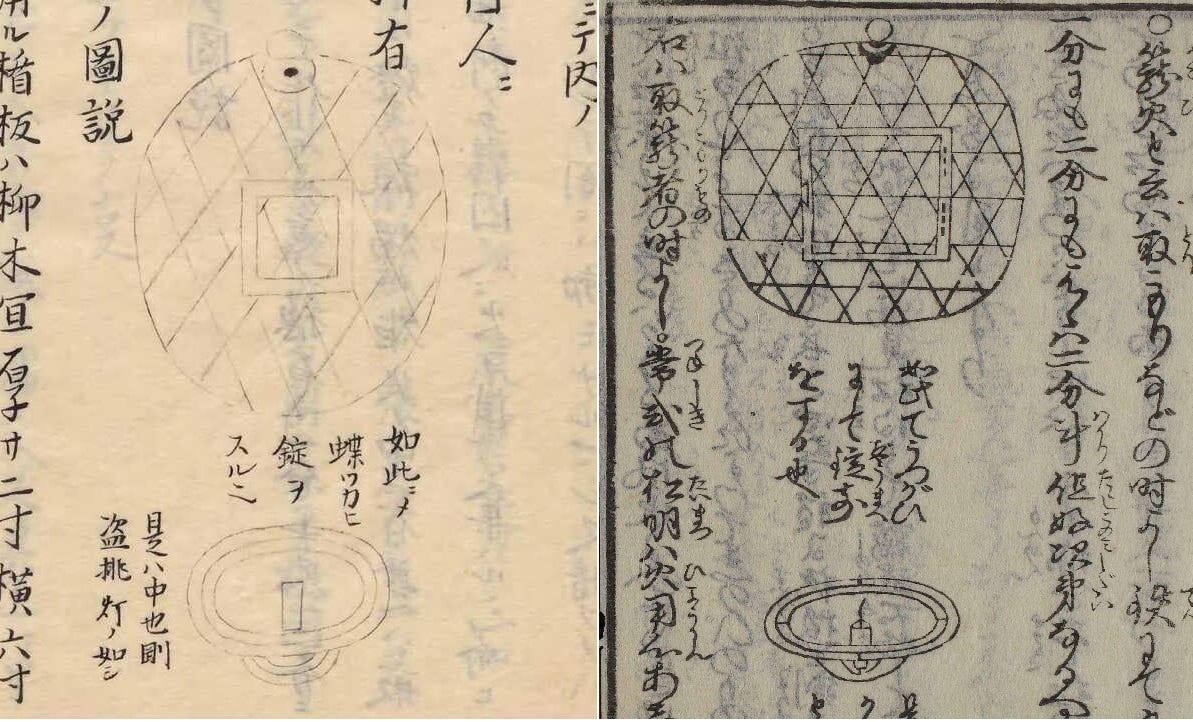

This is a design for essentially a land mine:

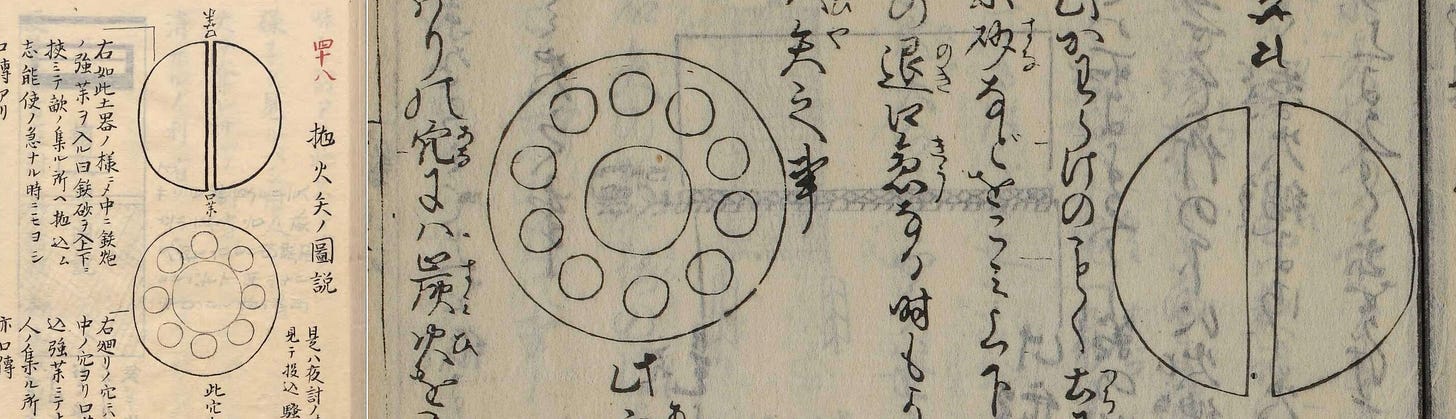

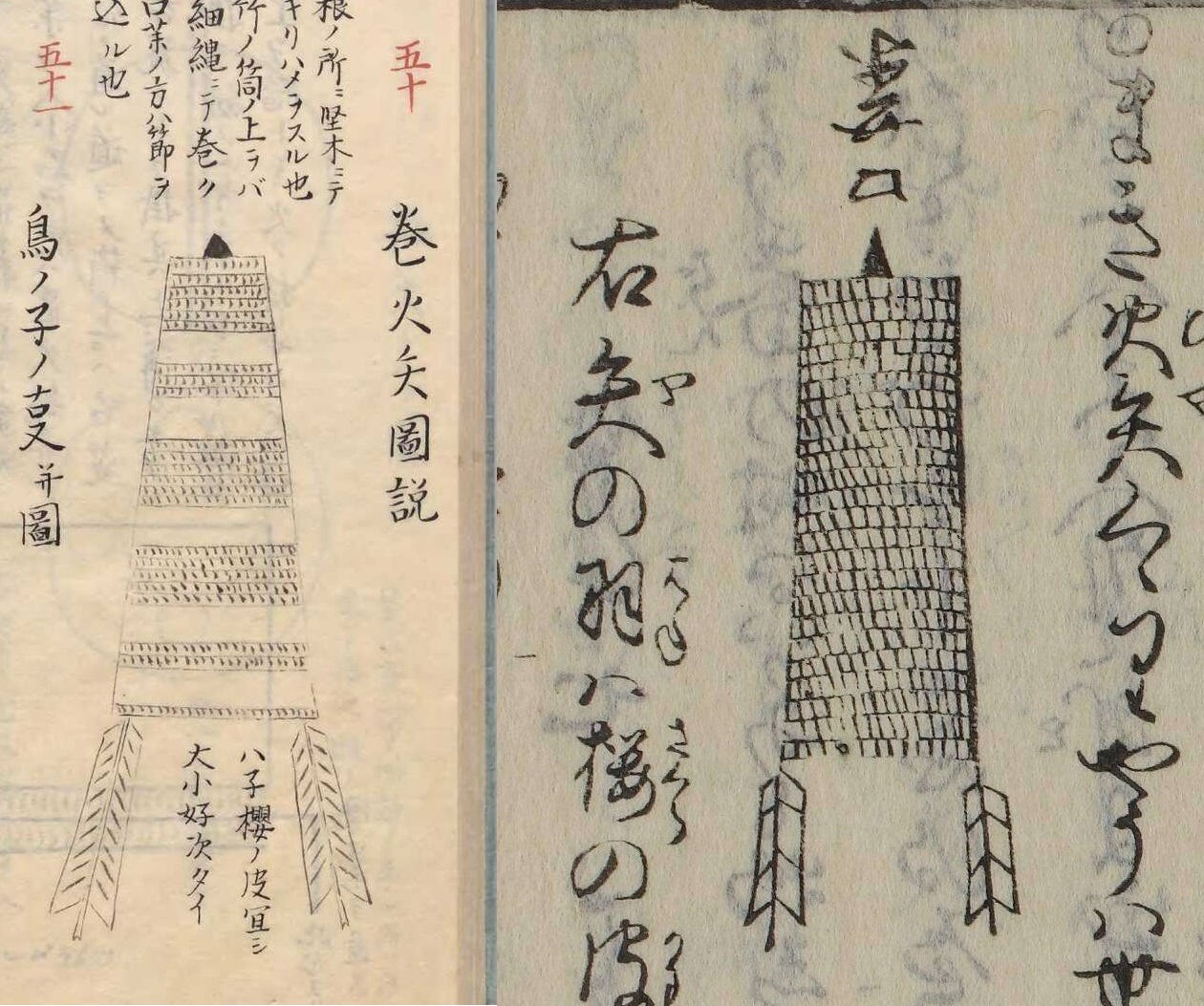

And this…well, I’m not really sure what this is. It’s described as a “wrapped fire arrow,” and from the description in both texts I think the idea is that some kind of explosive or incendiary is supposed to be contained in the wrapping, but I can’t see how you could fire this from a bow effectively:

It looks like something from the Mel Brooks film Robin Hood: Men in Tights, to be honest:

Anyway, since the lifting from Warrior Service is pretty much undeniable, the question would be what this might mean for how we interpret BSSK. An uncharitable interpretation would be that Fujibayashi had no personal knowledge or experience of these devices and simply copied them from other widely-available texts, then presented them as authentic Iga and Koka shinobi knowledge. What’s more, I noted in an earlier post that the so-called ‘ninja manuals’ are easily critiqued on grounds of general implausibility, historical distance, and lack of corroboration, and the same criticisms could be leveled at Warrior Service too. An even less charitable interpretation, then, would be that Fujibayashi was a bullshitter copying someone else’s bullshit, so it’s bullshit all the way down.

A more charitable interpretation might be that the above actually were real shinobi devices and Fujibayashi just got a bit lazy, deciding to copy the relevant sections from Warrior Service rather than re-invent the wheel. That’s certainly possible, though if we accept that argument, we’d also have to concede that the stuff in BSSK was probably not unique to Iga and Koka shinobi but was widely known and used across the entire country. Not exactly SECRET NINJA WISDOM, then.

Two People Can Keep a Secret…

This brings me to my second point, which is the idea of secrecy surrounding all of this supposed shinobi knowledge. In BSSK, for instance, Fujibayashi repeatedly informs us that certain aspects of knowledge about these devices (and about shinobi warfare in general) are transmitted through oral teachings only, rather than being written down. Anthony Cummins, in his intro to the English translation of BSSK, also writes that:

[T]he hidden world of the shinobi is no longer in the darkness, nor is it covered by the whisper, ‘it is secret,’ but it is here and fully in the light for all to enjoy.4

I mean, I get it. It’s marketing, right? And this sort of thing works because Western audiences just know, on a kind of semi-conscious cultural level, that Asian countries have all kinds of profound and hidden wisdom. This explains why everyone was so keen to explain Marie Kondo’s schtick as Shinto’s supposedly ancient teachings, for instance. It’s Mr. Miyagi in the Karate Kid, it’s the Beatles and the Maharishi Mahesh Yogi, it’s basically the whole plot of Last Samurai, and God knows how many other examples. This is one of the cultural roles that Asia plays in the Western consciousness, a storehouse of ancient and mystical wisdom that will soothe the minds of Westerners dissatisfied with industrial modernity. And publishers, obviously, are well aware of this - it’s why Alexander Bennett’s translation of the early 18th century samurai ethics text Hagakure has the tagline “The Secret Wisdom of the Samurai,” to give just one of many possible examples.

Two points in response to this. One is that, as we’ve just seen, certain sections of BSSK were not remotely secret knowledge. The text from which Fujibayashi was apparently copying, Warrior Service, was commercially published in 1653 and survives in at least six known editions, meaning it sold well enough that publishers kept printing it and putting it out all over Japan.5 Pretty much any samurai in the country could have accessed the wisdom therein (and by extension, what’s in BSSK) by going to a bookshop in the nearest city. This stuff was probably as close to general military knowledge as you were likely to get in the 17th century.6

The second point is about the nature of oral transmissions and secret teachings (hiden, or kuden in Japanese).7 Secret teachings were a fairly common element in many medieval and early modern Japanese cultural endeavors, ranging from martial arts to poetry. We might easily assume that such secret teachings were where the real knowledge and mastery was, that (say) the really secret knowledge of the shinobi was jealously guarded because it was devastatingly effective.

Yeah. Not necessarily.

In the field of medieval and early modern Japanese poetry, which is one I’m reasonably familiar with, there was a corpus of secret teachings passed on through various noble families over many generations. These were considered so important that in 1600, toward the end of the Warring States period, the Emperor himself sent an envoy to try to ensure the safety of one of the last surviving recipients when he was under siege in his castle.8 The thing is, though, that some of these secret teachings eventually came to light, and…they were pretty underwhelming. One set of them, for instance, consisted of the actual identity of certain birds mentioned in certain centuries-old poems. Imagine a poem that opens with, “Hark! Birdsong!,” and then someone tells you, in strictest secrecy, that the ‘bird’ in question is actually…wait for it…a crow! And this is knowledge you’ve been waiting twenty years to be let in on.

This isn’t just me being a cynical, ignorant Westerner, by the way. The 18th century Japanese philologist and poetic scholar Motoori Norinaga, who was philosophically opposed to secret teachings in poetry, is known to have remarked, sarcastically, “Well, thank the gods they kept that secret - imagine if anyone had figured out that the bird was a crow!” (I’m paraphrasing, obviously, but you get the idea).9

What I’m saying, then, is that sometimes in Japan it was more about the fact that secret knowledge existed and could be used as a source of in- and out-group identity, not necessarily its practical use-value. I don’t think there’s any realistic way now of recovering the BSSK’s ‘oral teachings,’ but there’s a decent chance that even if we could, they wouldn’t be particularly useful - or even all that interesting.

For next time, we’ll wrap up our discussion of ‘ninja manuals’ by considering the basic implausibility of quite a few of the tools featured therein.

Kanji: 軍法侍用集. This text was first published commercially in 1653, though it probably existed and circulated in manuscript form before that date - we don’t know for sure.

Fukushima Takahito, “Ninjutsusho seiritsu ni taisuru heihōsho no eikyō: Bansen shūkai to Gunpō jiyōshū o hikaku shite” [=The influence of military manuals on the compilation of ninjutsu texts: a comparison of Bansen shūkai and Gunpō jiyōshū] in Yamada Yūji, ed., Ninjagaku taizen [Complete Guide to Ninja Studies] (Tokyo UP, 2023), pp. 4-17.

If you want to compare the Japanese, the original text is as follows:

投火矢の事。是は夜討の時、敵の集まりたる所へなげこみ、敵をさわがすなり。(Warrior Service)

是ハ夜討ノ時敵ノ集ル所ヲ見テ投込騒ガシ打ツ (BSSK).

You can check for yourself at cell 192 here and p. 29 here. For a full comparison of similar passages between the two texts, see Fukushima, “Ninjutsusho seiritsu ni taisuru heihōsho no eikyō,” p. 12.

Cummins, “Author’s Notes” in The Book of Ninja, p. xiii.

Fukushima, “Ninjutsusho seiritsu ni taisuru heihōsho no eikyō,” p. 5.

Hiden 秘伝; kuden 口伝.

This was Hosokawa Fujitaka, also known as Yūsai 細川藤孝 (幽斎, 1534-1610).

Motoori Norinaga 本居宣長 (1730-1801). If you’re really interested, check out Maki Isaka Morinaga’s Secrecy in Japanese Arts (Palgrave Macmillan, 2005), p. 14.