Copying Off Other People: An Actual Shinobi Tradition

On the Provenance of Certain Parts of Bansen shūkai

In our previous post we introduced the 1676 text Bansen shūkai, sometimes referred to by English-language writers as the ‘ninja Bible.’ If you’re not already familiar with it, Bansen shūkai (or BSSK, as I’ll refer to it below) is a pretty important text for the modern ‘ninja’ mythos, as it claims to be a compendium of tools and techniques used by the historical shinobi. It’s certainly been presented that way to English-speaking audiences, anyway, especially since the 2013 publication of an English translation of the text by Minami Yoshie with an introduction by Anthony Cummins.

We also saw, though, that almost as soon as the ‘ninja’ boom of the early 1960s in Japan had begun, there were critics pointing out that parts of BSSK look an awful lot like the contents of certain Chinese-produced military manuals. Both the horribly unreliable ‘ninja’ ‘historian’ Okuse Heishichirō and the novelist Murayama Tomoyoshi had made this point in print as early as 1964, and more recently Prof. Takamura Takayuki of Meiji University took it up in a presentation at Mie University in 2014. As you’ll know if you read the previous post, Takamura noted the similarities between BSSK and the late Ming Chinese military manual A Chronicle of Military Preparedness (Wubei zhi, 1628), and concluded that some of BSSK appears copied from the latter. For this reason, according to Takamura, we can’t necessarily say that all of the BSSK is authentic Warring States shinobi knowledge from the province of Iga and the region of Koga.

So is Takamura right? What exactly is the nature of the BSSK’s borrowing from Military Preparedness?

One pretty important principle in ‘ninja’ history is to always demand evidence; never accept an historical claim on the strength of someone’s word or credentials. ‘Ninja’ writers, as you will realize by now, have an appalling habit of advancing claims without any supporting evidence whatsoever (consider Okuse’s ideas about dipping shuriken in horse dung, for instance). Frankly, we wouldn’t be in half the mess we are now if editors, scholars, and readers over the last 50 years hadn’t tended to assume that some dude must know what he’s talking about because he’s Japanese/is a 91st generation NINJA GRAND MASTER/has spent, like, three weeks in Japan/has a PhD in something Japan-related/etc etc.

He Who Would Climb a Ladder…

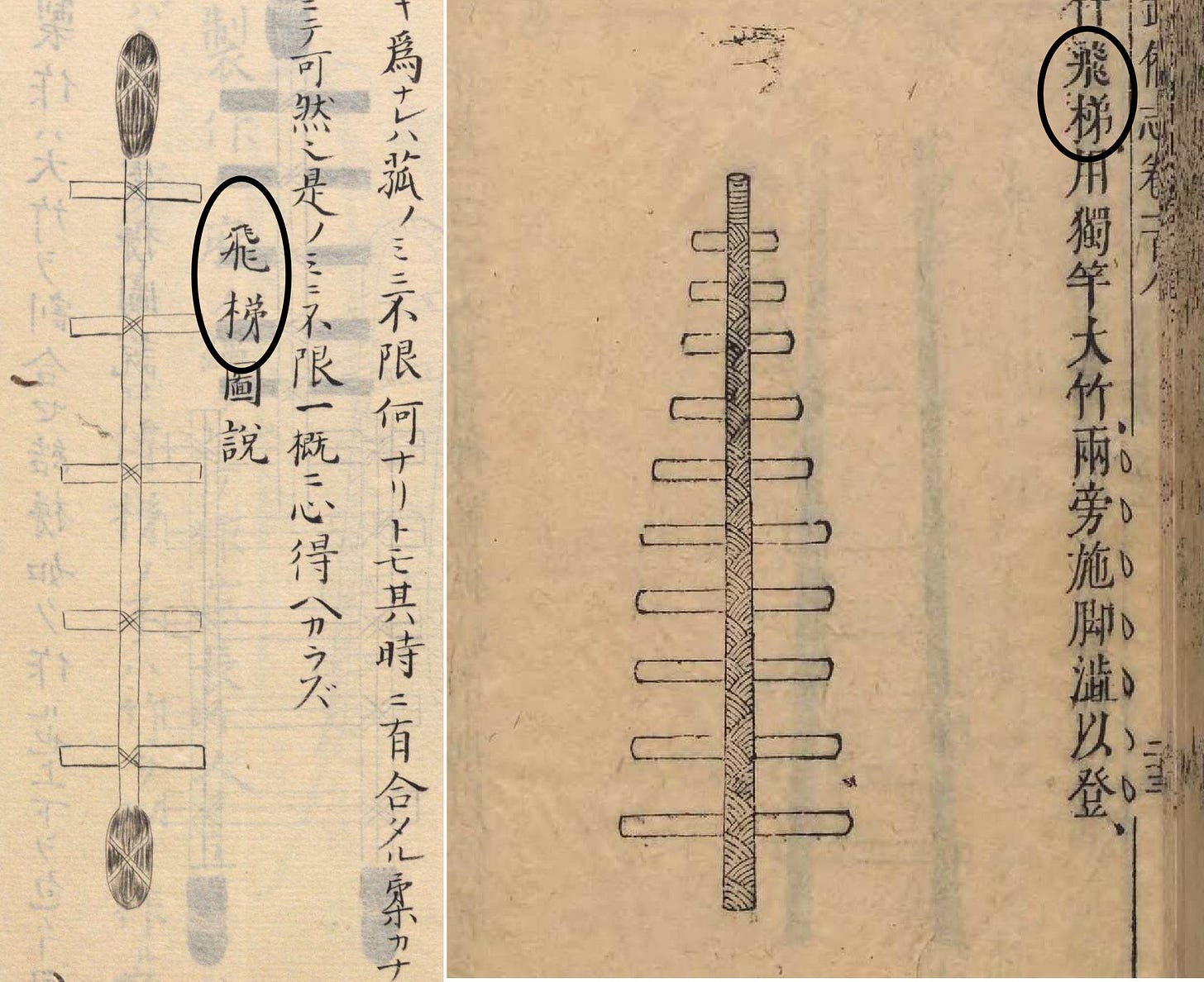

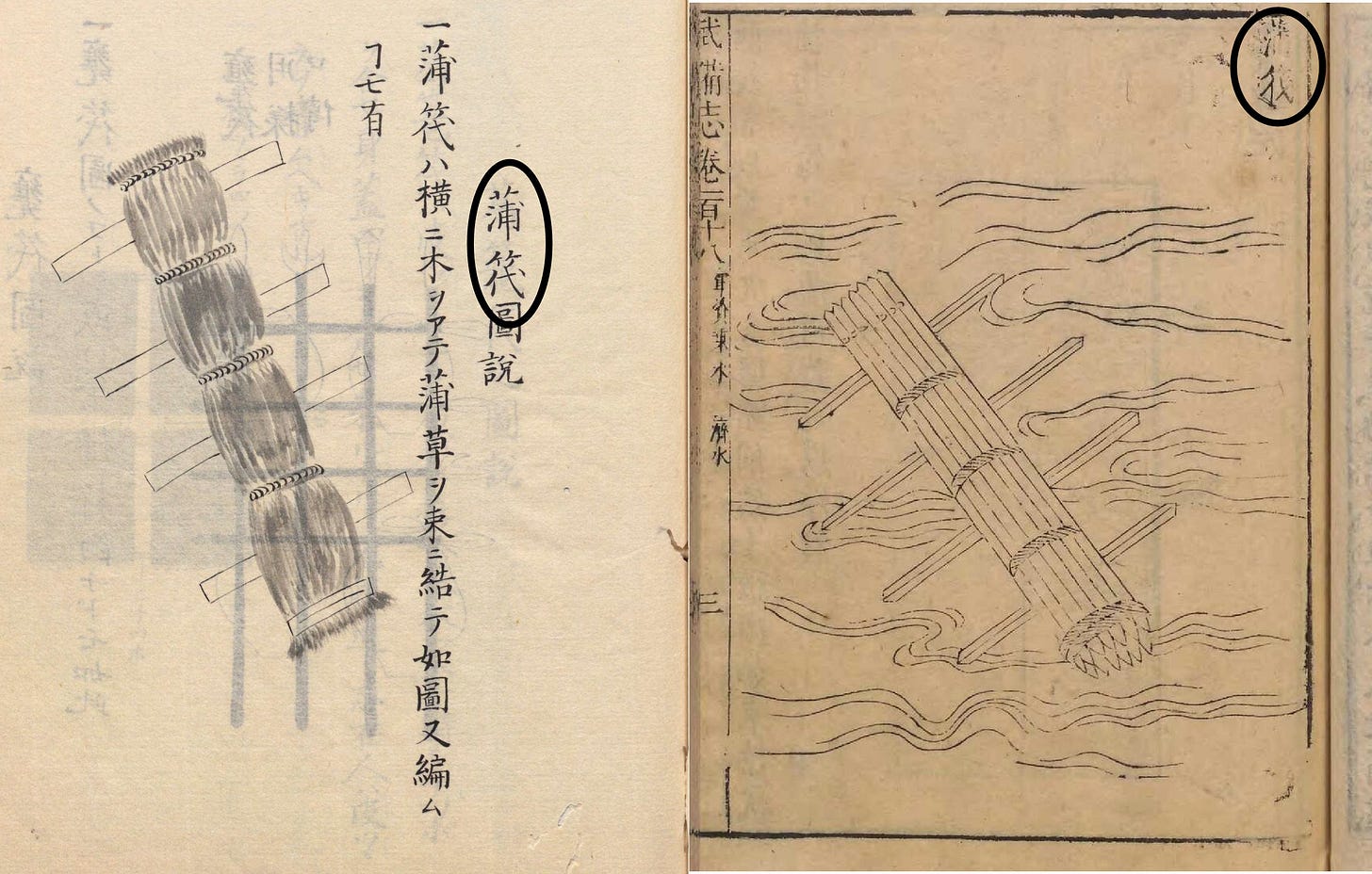

And after all, there are only so many ways that you can make a ladder, right? Consider the below examples, for instance, with BSSK on the left and Military Preparedness on the right:

This is referred to in both texts as a “flying ladder” (飛梯, J. tobihashigo, Ch. feiti), as you can see if you can read Japanese or Chinese (I’ve circled the text in question to make it easier to see ). The drawings aren’t absolutely identical, obviously, and it’s certainly possible that Japanese shinobi could have come up with a similar device independently. It’s a bit harder to imagine a stealthy shinobi carrying an eight-foot ladder around, though; the ‘flying ladder’ definitely does seem better suited to use in the kind of large-scale siege warfare Military Preparedness is discussing. But so far, I don’t think we’d say this is definitive proof of copying.

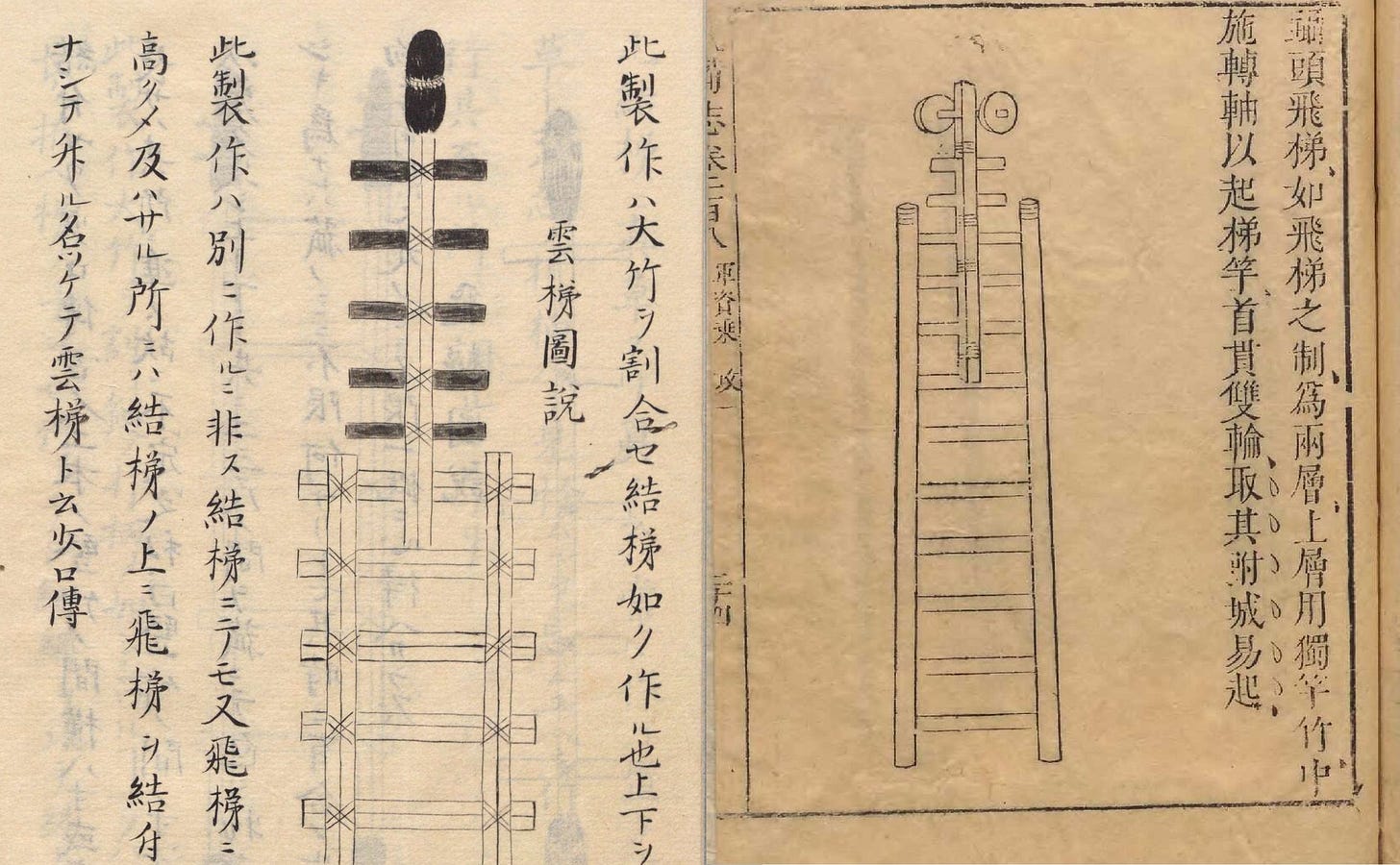

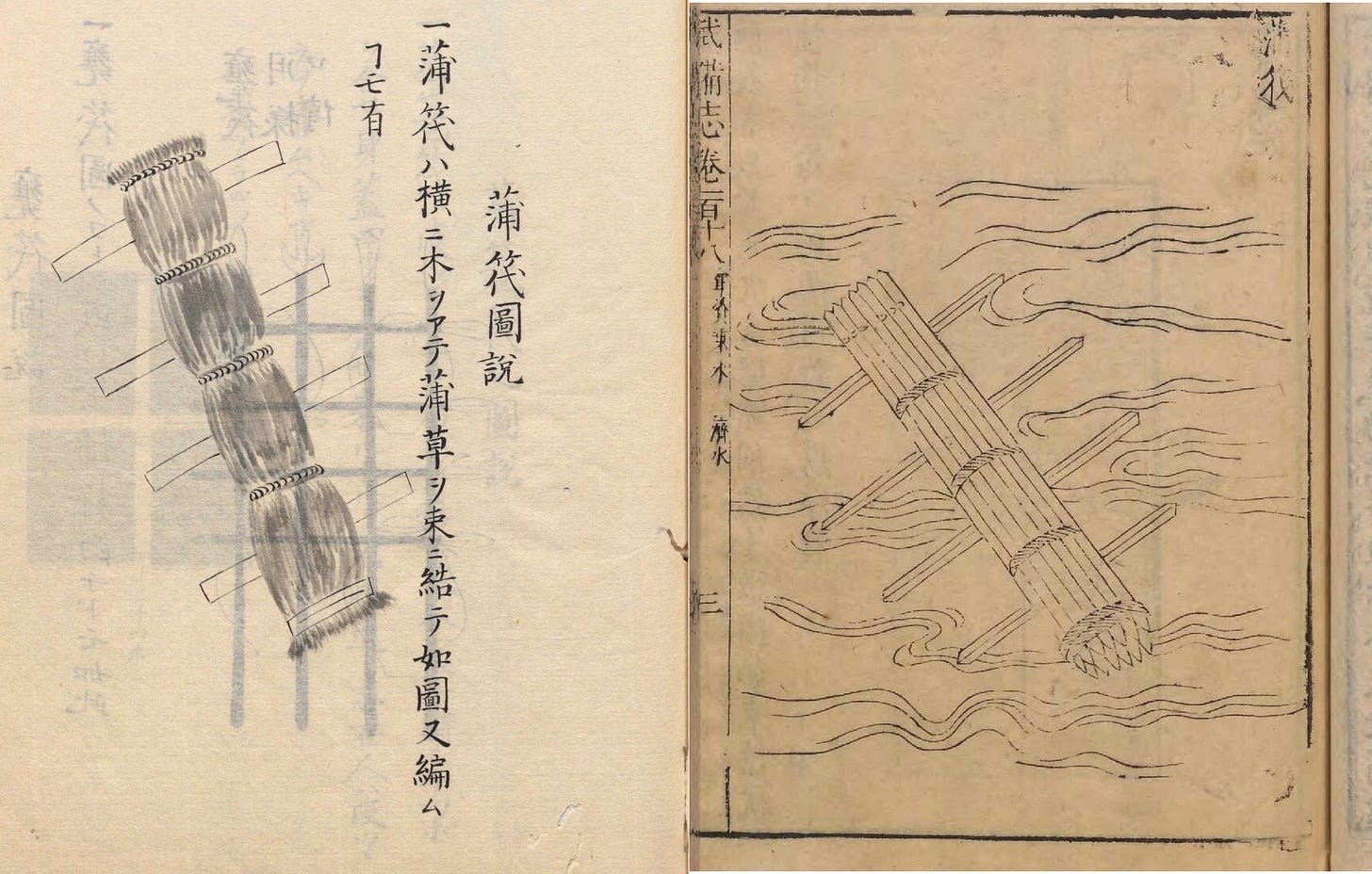

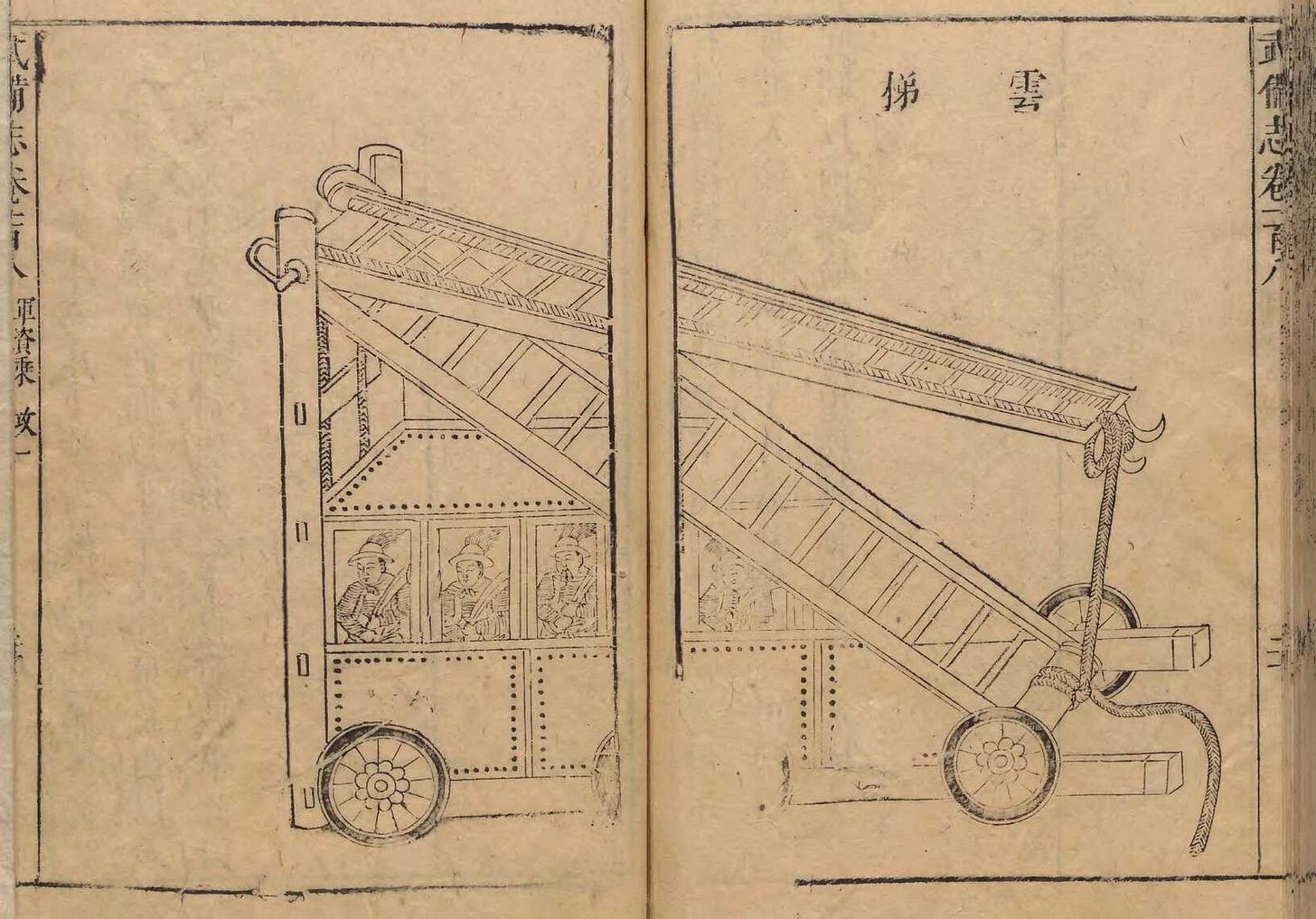

Since we’re on the topic of ladders, there’s also this from the same section in both books:

Military Preparedness refers to this device by a name that literally translates, amusingly enough, to something like “standing-on-tiptoes head flying ladder” (蹑頭飛梯 nietou feiti - I think I’ll just call it the ‘tiptoe ladder’ below). BSSK, on the other hand, calls it the “cloud ladder” (untei 雲梯). The BSSK’s re-naming might strike you as a little odd if you’re familiar with East Asian military history, because the ‘cloud ladder’ in a Chinese context more commonly refers to a much larger siege engine, as we would actually find if we skipped back a mere three pages in the same volume of Military Preparedness:

I’m not sure what accounts for the re-naming, though it occurs to me that just maybe, Fujibayashi did it because he didn’t know the graph 蹑, for ‘standing on tiptoes’ - it’s a fairly obscure one and I had to look it up myself. The description for how to make the ‘tiptoe ladder’ and the BSSK-type ‘cloud ladder’ are exactly the same in both texts - you’re supposed to attach a ‘flying ladder’ onto a regular ladder to give you that extra reach. Perfect for those times when you just can’t get over the castle walls, I would assume. Although again, it’s hard to imagine a lone assassin carrying two eight-foot ladders around with him. Perhaps the idea was that this could be improvised from available materials, or carried in a squad of shinobi, but again, this seems like something you’d be more likely to use in large-scale siege warfare.

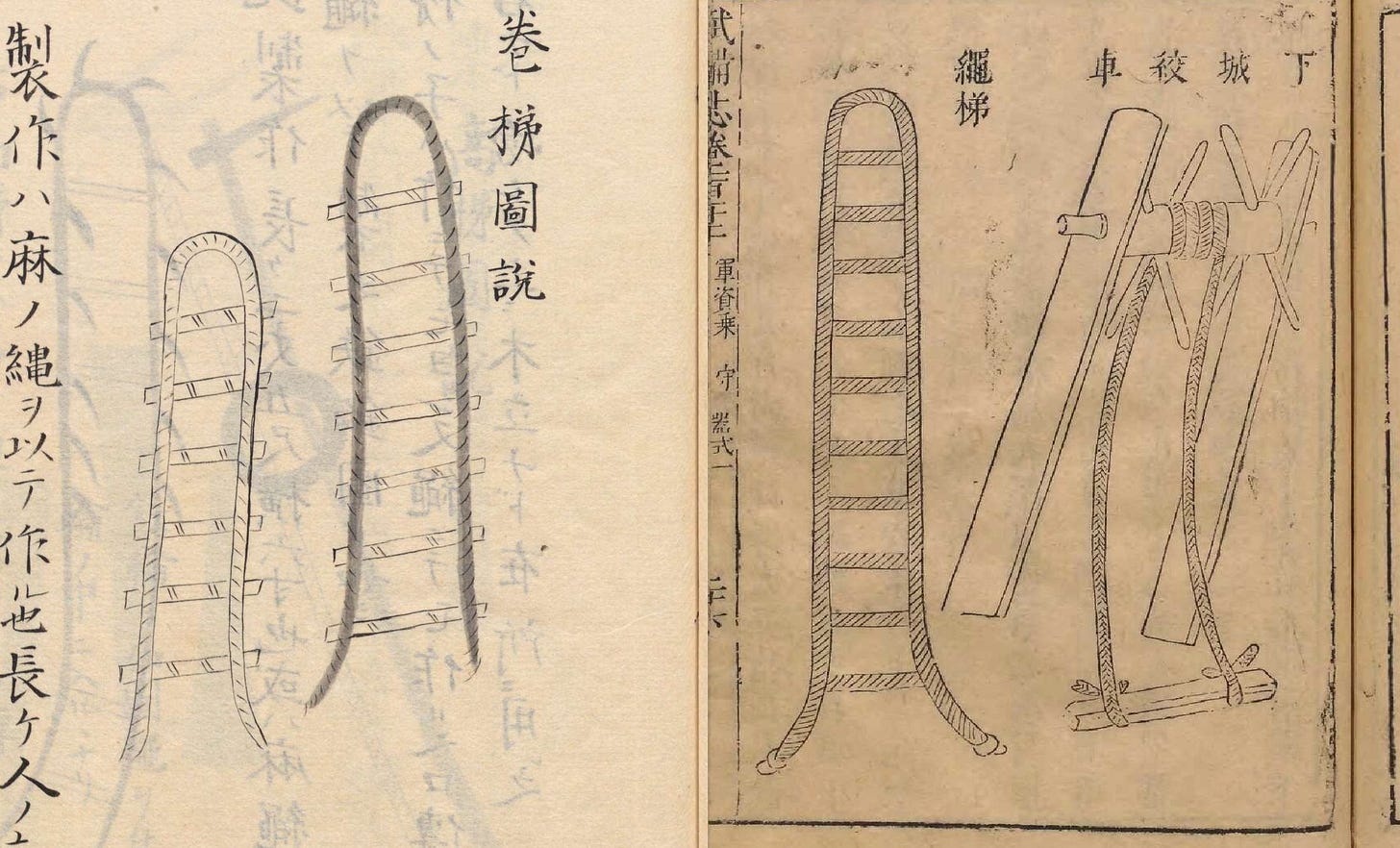

Slightly more plausible for a lone assassin are the below rope ladders, described as “rope ladder” (繩梯 Ch. sheng ti) in Military Preparedness and “rolled ladders” (makihashigo) in BSSK:

Arrows, Spears, and Reed Bridges

I’m not sure we’d call it a smoking gun, but on what we’ve seen so far we’d have to call it more likely than not that Fujibayashi was copying at least some of his ‘ninja tools’ from Military Preparedness. There are a couple of further examples I’d like to share, though, which I think move things from “balance of probability” to “beyond reasonable doubt.”

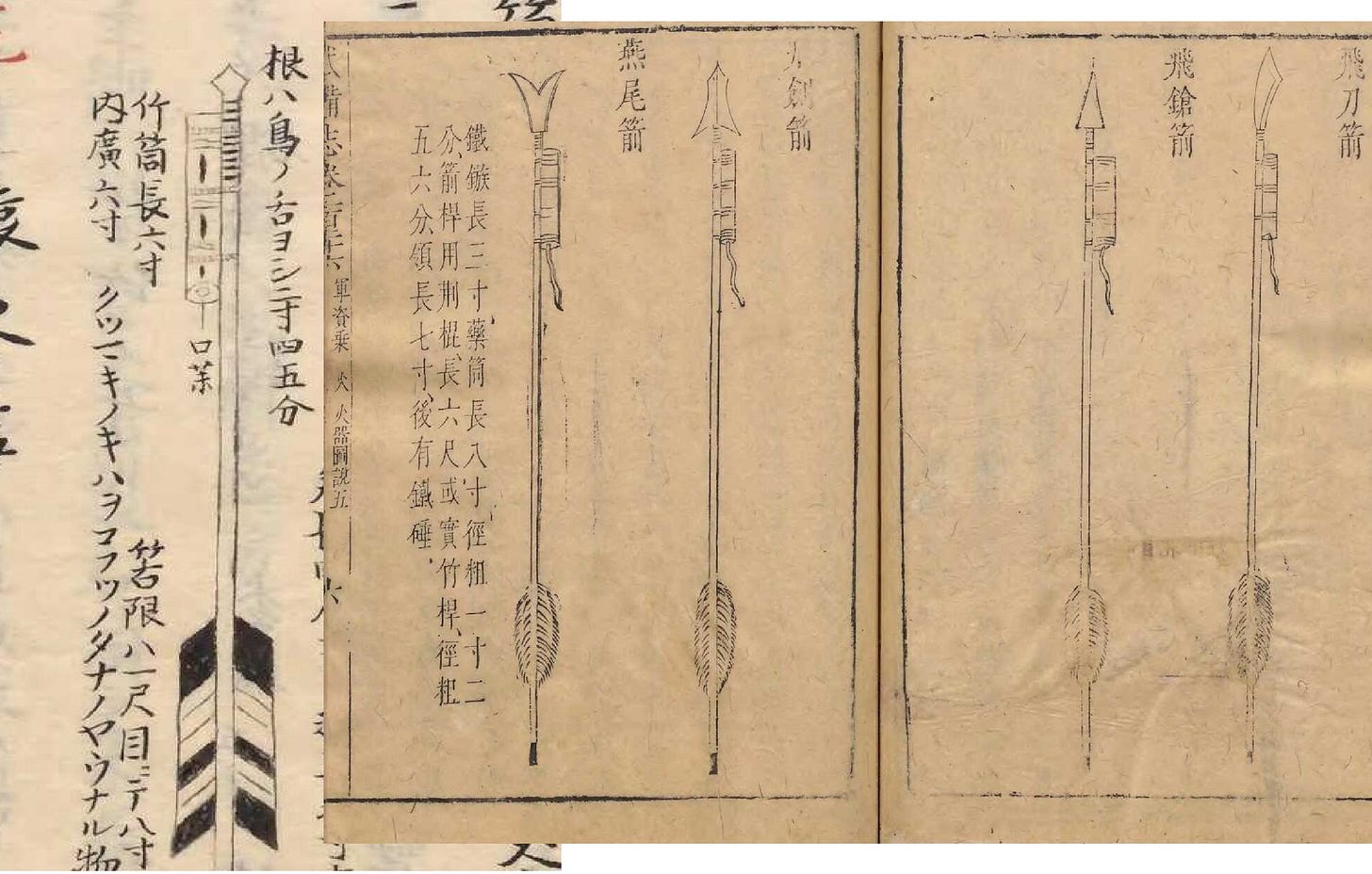

First are the illustrations of fire-arrows (or possibly rocket-powered arrows!) in both texts (as before, BSSK on the left, Military Preparedness on the right):

The similarity doesn’t necessarily prove direct copying - after all, fire arrows were widely used in East Asia. Japanese troops during Hideyoshi’s invasion of Korea between 1592 and 1598 would likely have come across something very similar to this being launched at them from a weapon of Korean design known as the hwacha or ‘fire-cart.’ This fired off volleys of dozens of rocket-powered arrows, as you can see here, and seems to have been a pretty effective weapon against the Japanese forces. This makes me think that the fire-arrow design seen in BSSK was probably common knowledge across East Asia, rather than a specifically shinobi thing.

But there are also other devices and passages where direct copying seems far more likely. Consider the below, the splash image for today’s post, which is presented as part of a selection of tools with which to cross water:

This is supposedly a temporary bridge made out of bundled reeds used to cross water. The name is the same for both (蒲筏, literally ‘reed-raft’; the printing quality does makes the graphs hard to read with Military Preparedness, but that’s what it says), and the picture is pretty much identical, even down to the angle at which the bridge is lying. Here, I’d say it’s almost certain that Fujibayashi copied this directly from Military Preparedness.

There are also a couple of other examples where the BSSK text describes something that sounds a lot like a device depicted or described in Military Preparedness. For instance, what BSSK refers to as “fire to be be attached to a spear when facing a large group of enemies” (敵大勢ノ向フトキ槍ニ付ル火) looks a lot like this device from Military Preparedness:1

Perhaps it’s just me, but I thought that openly attacking a large force of enemies was precisely what shinobi were not supposed to be doing. And spears, being very long weapons, don’t exactly lend themselves to concealment. Again, it seems more like a weapon that a large conventional army would prepare and use, but then I suppose it’s always possible that this was an emergency tactic or a special weapon for a shinobi.

So Just How ‘Ninja’ are these ‘Ninja Tools’?

Based on the above, I think we’d have to say that in legal language, BSSK does have a case to answer. Takamura seems to be on firm ground in noting the similarities between BSSK and Military Preparedness, that many of the ‘ninja tools’ seem more suited to large-scale siege warfare than small-group infiltration operations, and that the apparent copying should push us to reconsider the assumption that BSSK is entirely based on shinobi knowledge specific to Iga and to the Koga region.

HA! BUSTED! Now we can throw BSSK out of the window and dismiss the ‘ninja’ as total bullshit, right?

No.

Let me clarify what I’m trying to do here. Historical scholarship of textual materials should not follow a doctrine of inerrancy; it does not follow that if one or several parts of BSSK are shown to be unreliable or copied from other sources that the whole thing should be thrown out as worthless. The fact that the BSSK is sometimes nicknamed the ‘ninja Bible’ does not mean we should follow the fundamentalist logic that either all of it is true or none of it is. The point I am making is that BSSK is an historical document, and like all historical documents, should be read critically and assessed for reliability.

This really shouldn’t be a controversial point, but the question of BSSK’s reliability seems to be lacking from most English-language discussions of BSSK, and quite a few Japanese ones too. The intellectually honest reading of BSSK would be that in most cases we simply don’t know whether its contents are authentic shinobi practice at all, and in more than a few cases there’s evidence that they weren’t. As I’ve said before, I think you’re on firmer ground reading BSSK and other similar texts as evidence of what 17th century writers thought shinobi might have done, not so much of what they actually did.

But of course, you don’t get this from the existing ‘ninja’ literature. Cummins’ introduction to the BSSK translation, as far as I can see, doesn’t make any serious effort to consider the possibility that the BSSK might not be exactly what it appears to be, even though the problems with it - copying from Chinese sources and the basic implausibility of a lot of the devices - were known as early as the 1960s.

Since we’re on the subject anyway, perhaps we should delve a bit deeper into the sources and nature of BSSK. In the next post, I’d like to show how other pieces of BSSK also seem to have been copied from another roughly contemporary military manual, a Japanese-produced one that was not remotely ‘secret wisdom’ but actually commercially available and widely read among the samurai class. And I’d also like to briefly consider how the rhetoric of ‘secret teachings’ in Japan might apply to BSSK, and how it doesn’t necessarily imply what you might think about the knowledge therein.

BSSK vol. 18, n.p.; Minami, trans., The Book of Ninja, p. 437.