The Shinobi's Ancient Chinese Secrets

How Much of What's in the 'Ninja Manuals' is Specifically Japanese?

A lot of what is presented to modern pop audiences as ‘ninja lore’ derives from various military manuals written in Japan during the Edo period (1600-1867). These manuals, which claim to contain the tools and techniques of the historical shinobi, seem to have passed largely unnoticed until between about 1910 and 1940, when ‘ninja’ writers such as Itō Gingetsu and Fujita Seiko brought them to the attention of their readers. Despite Gingetsu and Seiko’s efforts, these texts remained mostly obscure until the full-on ‘ninja’ boom of the late 50s and 60s began, after which they were obviously catnip to publishers trying to capitalize on contemporary trends.

One of the most famous such manuals is the Bansen shūkai, which we touched on a bit in the previous post. BSSK, as we’ll refer to it from now on, is believed to have been completed in 1676 by a man named Fujibayashi Yasutake, who was probably a low-ranking samurai but about whom we know very little.1 Its contents consist mostly of a history of stealth warfare in Japan, explanations of techniques of infiltration and concealment, methods of divination, and a fairly long group of sections with various apparent equipment for shinobi use. These sections contain things like recipes for poisons and explosives, tools for infiltration, and a few weapons (though not shuriken, as we’ve previously noted).

BSSK itself seems to have first surfaced in the mid-1930s in Japan. I’m not certain, but I think it was probably Fujita Seiko who introduced the text to general audiences, since Seiko possessed one of the first known modern copies of the manuscript. Seiko’s immediate predecessor Itō Gingetsu doesn’t seem to refer specifically to BSSK in his writings, so it’s entirely possible that Gingetsu didn’t know about it until Seiko drew attention to the text in his writings. There’s a reference to BSSK in a book by another author on secret societies in Japan published in 1935, and Seiko himself was obviously using it as a source by 1938, since its influence is clearly visible in his 1938 book What is Ninjutsu?2

Murayama Tomoyoshi Reads Bansen shūkai

I’ve already discussed what I see as the proper critical approach to Edo-era ‘ninja manuals’ in the previous post, so I won’t repeat myself here. Instead, we’ll look at a few things that are specific to BSSK’s contents and which should inform our thinking as to how seriously we can take its claims about the historical shinobi, particularly the tools they are supposed to have used.

21st century writers in both Japan and the English-speaking world tend to present the contents of BSSK uncritically, as if the text is unquestionably an accurate record of what the historical shinobi did. This was not necessarily the reception that the BSSK received in 1960s Japan, however; in fact, a number of the more prominent proponents of the new ‘ninja’ mythos were openly skeptical of its reliability as a source. Surprisingly, the ‘ninja’ historian and mayor of Ueno City Okuse Heishichirō was among the skeptics, but we’ll cover his objections in the next post.

For now I want to focus on the comments of the playwright and novelist Murayama Tomoyoshi. Murayama, for those of you who don’t know, was a respected avant-garde playwright and writer who had been arrested several times by the Japanese thought police during Japan’s militarist era in the 1930s. Murayama was also a staunch Communist, which had a lot to do with both his prewar arrests and his postwar interest in ‘ninja,’ but we’ll cover that another day.

Murayama was the author of the ninja novel series Shinobi no mono, which he serialized from 1960 onward and which was adapted into the 1962 film of the same name. As well as depicting plenty of exciting ‘ninja’ action, Murayama’s novel also contains points where he stops to discuss what he thought was the ‘real’ history behind his topic. Naturally enough, then, he stops about half-way through the first volume to discuss the BSSK. Murayama appears to believe that the stuff depicted in BSSK is mostly genuine ‘ninja’ tools, but he also has this to say:

There are parts [of BSSK] that contain little more than ninja tools that could never actually be used and of which the author probably had no direct experience, as well as sections which seem to be little more than reproductions of the Chinese military manuals A Chronicle of Military Preparedness (Wubei zhi) and The New Book of the Military Marquis Zhuge (Zhuge Wu Hou xinshu).3

So there are two main points of critique here, the first being that some of the supposed ‘ninja tools’ look like bullshit, in that they would be highly unlikely to work in the real world. The second point is that substantial sections of BSSK seem to be copied from Chinese military manuals, and it’s this last point I want to address in more detail below.

Another Time and Another Place

To think through the implications of Murayama’s critique a bit more concretely, the essence of the objection is that if Fujibayashi Yasutake was simply copying out sections from Chinese-produced military manuals and including them in the BSSK, that would naturally call into question just how specifically ‘ninja’ the tools and techniques were. We’d have to consider the possibility that the tools and techniques in BSSK were not real shinobi stuff at all, but material lifted from a different context and passed off as authentic Japanese shinobi knowledge. A more charitable reading would be that perhaps the shinobi had copied and used tools that were known in China. Fair enough, but that would still raise the question of how specifically ‘ninja’ the items were, if they were widely known across East Asia and available to everyone. Imagine a Japanese historian gushing over how CIA assassins used a special tool called a “screwdriver,” and you’ll get the general idea.

Since this issue speaks directly to the BSSK’s overall credibility as a ‘ninja’ source, it’s not surprising that Anthony Cummins addresses it in the intro to Minami Yoshie’s 2013 English translation of the BSSK. Cummins addresses two main points he sees as major misconceptions. The first is that BSSK is written entirely in Chinese, which is a bizarre point to focus on - it obviously isn’t, and I don’t know any serious scholar who’s claimed that it is.4 The second is the idea that Fujibayashi Yasutake was simply “stealing” (Cummins’ term) Chinese military ideas:

Primarily, Fujibayashi uses anecdotes from the Chinese classics to add support and credence to his ideas…He appears to be unaware of, or fails to state, the probable Chinese origins of other tools that had been in existence in Japan for a long time.

Therefore, on the whole, it can be concluded that Fujibayashi was not ‘stealing’ from Chinese texts, but simply utilizing them to support his theories.5

I’m not really convinced by Cummins’s attempted rebuttal here, mostly because more recently the Japanese scholar Takamura Takayuki of Meiji University has looked at BSSK and its similarities to Chinese military manuals, particularly the Chronicle of Military Preparedness Murayama mentions above, and Takamura’s conclusion is rather different.

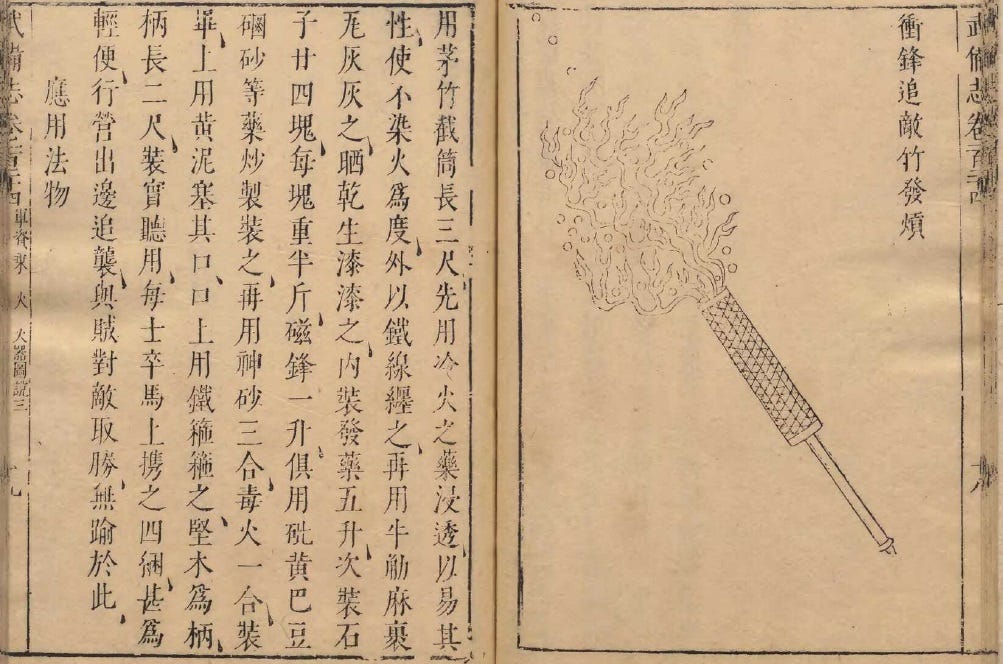

Military Preparedness itself was written by a Chinese scholar named Mao Yuanyi, completed in 1621, and made public in 1628.6 It’s a huge work, consisting of 240 volumes, and it’s known to have been imported into Japan by 1664, so its contents would definitely have been available to Fujibayashi.7 A copy of Military Preparedness is helpfully available through the Japanese National Archives, so I’ve been able to look at it. A lot of it is about divination, army formations and tactics, and siege warfare, but there are also some illustrations of weapons (conventional and otherwise), siege engines, and the like. The below, for instance, is a kind of firebrand weapon supposed to be used when charging into enemy lines or pursuing a fleeing foe:

Anyway, Takamura concludes that in certain sections of BSSK Fujibayashi does indeed appear to be leaning pretty heavily on Military Preparedness, to the extent that it calls into question how seriously we can take BSSK as an accurate depiction of medieval Japanese shinobi.

Here I’m using the summary and video of a presentation Takamura gave at Mie University in 2014, both of which are posted online. Takamura makes two main points that are of interest to us:

However, when one compares the BSSK’s shinobi tools to those mentioned in the Chinese Ming-era military text Chronicle of Military Preparedness (1621) by Mao Yuanyi, one can detect multiple cases where the tools are extremely similar to those in Military Preparedness. The military techniques, weapons, and strategy in Military Preparedness were developed against the background of mass group combat and siege warfare, both offensive and defensive, involving large cities. What we presume to have been the shinobi’s theatre of war is completely different, believed to have been clandestine infiltration, sabotage operations, and guerilla warfare; so even if we cannot say that the shinobi had no opportunity at all to use those ‘ninja tools’ that are so similar to those in the Chinese manuals, such opportunities would have been very limited.8

The point, then, is that Military Preparedness covers warfare of an entirely different nature to what the shinobi are generally supposed to have done - mass battle and siege warfare, rather than stealth and clandestine actions. That being the case, the reproduced tools seem at least incongruous and unlikely to have been widely used in real shinobi operations.

It’s also worth quoting part of the conclusion in the recording of Takamura’s presentation linked to below the text of the summary, as on his PowerPoint it says:

Insofar as we see numerous points of similarity between the Ming Chinese military manual Military Preparedness [and BSSK], it is hard for us to say that BSSK consists solely of parts that accurately relate the actual circumstances of Koga and Iga shinobi in Warring States Japan.9

In other words - and this is the point I have been making all along - you need to be extremely careful about assuming that everything you see in the ‘ninja manuals’ is real-world equipment that was used by actual shinobi, because, as Takamura argues, there are definitely parts of the text where that appears not to be the case.

The main question, then, would be: is Prof. Takamura correct? I think he basically is, and there are some notable similarities between specific sections of the two texts. It’s not quite the obvious lifting that more vociferous ‘ninja’ skeptics might want to see, but it’s fairly convincing proof of the textual connections nonetheless.

In the next post, then, we’ll take some time to do a visual comparison of certain passages in BSSK and Military Preparedness, and consider what these might mean for how we approach BSSK as an historical source.

Fujibayashi Yasutake 藤林保武 (dates unknown).

Seiko’s 1938 book contains images of the well-known mizu-gumo ‘water-spider’ device, for instance, which can only have come from BSSK. See Shahan, What is Ninjutsu (2021), p. 47; the original text is reproduced on p. 153 of Shahan, corresponding to p. 54 in Seiko’s original.

Murayama Tomoyoshi, Shinobi no mono 1:246. Japanese text: その上、著者が実際に経験したのではないと思われる実用不可能の忍具や、中国の兵書である武備録 [sic]、武巧新書 [sic] などからのただの引き写しに過ぎないと思われる部分もある。

The [sic]s are because Murayama apparently got the names of both of the Chinese manuals wrong in his original. The first one should be 武備志, while the second should probably be 武侯新書 or 諸葛武侯心書 (the precise titles seem to vary a bit).

Parts of BSSK are written in kanbun, which is basically classical Chinese as used by Japanese writers. This wasn’t at all uncommon in Japan and was roughly parallel to using Latin in medieval Europe; it certainly doesn’t make the text ‘Chinese.’

Minami, trans., and Cummins., ed. The Book of Ninja: The First Complete Translation of the Bansenshukai: Japan’s Premier Ninja Manual (Watkins Publishing, 2013), p. xxiii.

Mao Yuanyi 茅元儀 (1594-1640).

‘Volumes’ here is a translation of 巻 (J. kan, Ch. juan). This literally means ‘scroll’ and is usually used to divide up a pre-modern Asian work into sections. It doesn’t necessarily imply separate physical volumes, though, as sometimes multiple 巻 are contained in the same physical book. The importation date for Military Preparedness is attested to here.

Given the idea that Edo-period Japan was ‘cut off’ from the rest of the world, it may surprise some readers that Chinese books were available at all. In fact, though, there was a HUGE trade of books from China into Japan. So voluminous was the influx of Chinese-produced texts that once diplomatic relations were more-or-less normalized in the early Meiji period, Chinese scholars were able to recover certain texts that had been lost in China but had been preserved in Japan. If you’re curious about this, check out the first chapter of Will Fleming’s Strange Tales from Edo: Rewriting Chinese Fiction in Early Modern Japan (Harvard UP, 2023).

Translated from the summary of Prof. Takamura’s presentation at https://www.human.mie-u.ac.jp/kenkyu/ken-prj/iga/kouza/2014/20140614.html. Translation is mine.