(This is part of a series of posts on the kunoichi, or female shinobi, who didn’t exist. You can go back and look at the previous few posts if you need to bring yourself up to speed.)

Over the last few months in these pages we’ve mentioned the name of Donn F. Draeger (1922-1982) quite a bit. Draeger was a prominent American martial artist and author, who served in the US Marine Corps during WWII and received a BA from Sophia University in Tokyo in 1959. Over the next couple of decades Draeger spent a great deal of time living in Asia, training in, teaching, and writing about Asian martial arts. He remains to this day one of the most prolific authors on the topic of world martial arts in English, with at least fourteen books on different martial traditions for which he is listed as sole or co-author. He was a genuine pioneer in the popularization of martial arts in the West, and as far as I can tell is still well-respected among martial arts practitioners.

Ninjutsu: The Art of Invisibility

Possibly Draeger’s most influential book was his Ninjutsu: The Art of Invisibility, first published in 1971. Like Andrew Adams’ 1970 Ninja: The Invisible Assassins, Draeger’s Ninjutsu sold exceptionally well. The book’s title changed a few times over the years, so it’s hard to be sure, but Ninjutsu probably went through around ten editions between 1971 and 2011.1 It was also translated into Spanish in 1983 as Los Guerreros Ninjas and into Italian in 1991 as Ninjutsu : l'arte dell'invisibilità.

All of the above is hugely impressive, by the way. Very few authors of any kind manage to write a book that remains in print for forty years, and this is a level of influence far beyond what most ‘respectable’ academics ever manage.

Anyway, since we’re focused here on kunoichi, let’s see what Draeger’s Ninjutsu has to say on the topic. We start out in fairly conventional fashion:

A child, either male or female, born into a professional ninja family was expected to carry on the family tradition. Training began at the age of five or six years and was carried out for the remainder of the person’s natural life…As skill in maintaining balance grew, the trainee was made to repeat the exercises at greater heights until no fear of high places was felt and he or she was capable of performing incredible feats of balance.2

So there were female shinobi as well as male ones, and both received the same kind of super-acrobat training. This claim is at least superficially plausible, although there are some red flags, notably that Draeger does not cite any evidence to support his claims or disclose where his information comes from, and the book has no bibliography.

So, what sort of things did the female ‘ninja’ get up to?

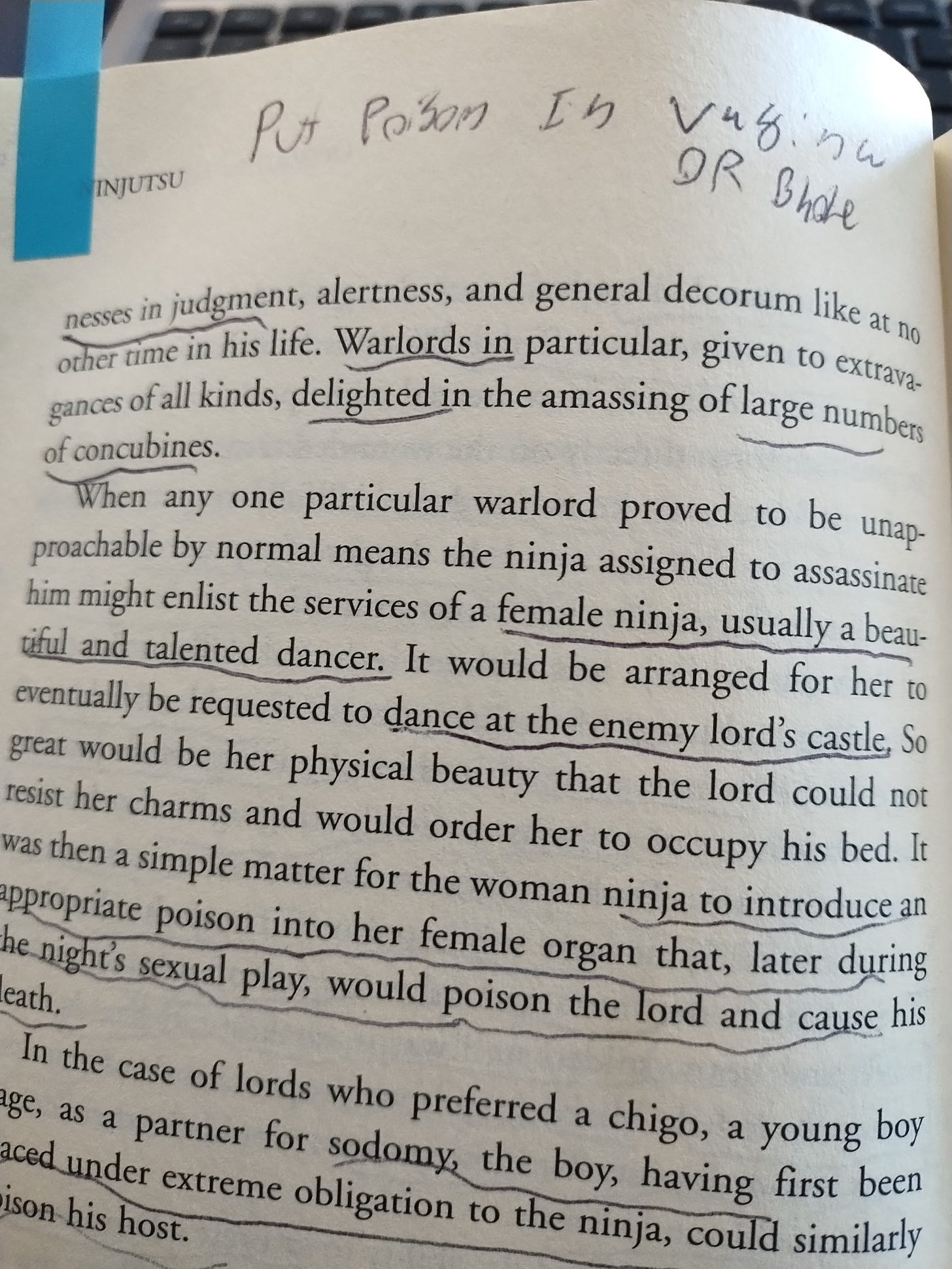

When any one particular warlord proved to be unapproachable by normal means the ninja assigned to assassinate him might enlist the services of a female ninja, usually a beautiful and talented dancer. It would be arranged for her to eventually be requested to dance at the enemy lord’s castle. So great would be her physical beauty that the lord could not resist her charms and would order her to occupy his bed. It was then a simple matter for the woman ninja to introduce an appropriate poison into her female organ that, later during the night’s sexual play, would poison the lord and cause his death.3

…what the fuck?

Poison vaginas?

Look, I’m not a toxicologist, but if you have a poison that’s absorbed through the skin and you…

…you know what, I’m not even going to bother.

Trying to assess the feasibility of this nonsense is taking it far too seriously. It sounds like something from one of pulp novelist Yamada Fūtarō’s semi-pornographic kunoichi novels, and I wouldn’t be at all surprised to learn that that was indeed where Draeger got the idea.

Oh, There’s More

As we saw in the previous post, Andrew Adams’ discussion of kunoichi in his 1970 Invisible Assassins elected to omit Japanese ‘ninja’ ‘historian’ Okuse Heishichirō’s claims that kunoichi operations could involve men seducing other men. Not so Draeger:

In cases of lords who preferred a chigo, a young boy page, as a partner for sodomy, the boy, having first been placed under extreme obligation to the ninja, could similarly poison his host.4

Extreme obligation, indeed.

My guess is that this one is probably from Okuse, given Okuse’s insistence that men did kunoichi seduction operations targeting other men. Even Okuse wasn’t crazy enough to suggest that ‘ninja’ put poison where the sun don’t shine, though.

Just in case you think I’m making all of this up and/or nobody could possibly take this stuff seriously, you may be interested to know that my 1989 copy of Ninjutsu is second-hand and bears a lot of notes made by its previous owner. The one at the top of this particular page, I am happy to relate, reads “Put poison in vagina OR Bhole:”

I’d just like to remind my readers that this is one of the best-selling and most influential ‘ninja’ histories of all time.

Elsewhere in Draeger’s Ninjutsu, we also have “Sodomy and the Secret Document,” the story of a ninja called Eda Hachirō, tasked with stealing a scroll on military secrets from a Buddhist temple in Kumano:

Eda Hachiro was a young teenage ninja, handsome and trained as a dancer and musician. Eda was to be sent into the Kumano compound in the role of a chigo, a page. Chigo were lavishly dressed by the monks and used in homosexual activities.

Eda faced his assignment without demur and through his youthful grace and beauty soon gained the attentions of the head abbot who had him transferred to his private quarters.5

Eda’s kunoichi operation succeeds, only for him to find that the scroll has been prepared “in a special kind of ink that would obliterate itself in sunlight!,” so the whole operation was a waste of time.

Draeger doesn’t give a source for this story, and I have absolutely no idea where he got it. I’ve searched on and off for a few years now, and I cannot find any mention in any Japanese source of a man named Eda Hachiro, or a military scroll in connection with the temple at Kumano. My best guess is that this too is a Yamada Fūtarō story, but if it is I haven’t found it yet.

In Case It Needs to Be Said…

It should be obvious by now that as a work of history, Draeger’s Ninjutsu is an absolute, unmitigated disaster, totally unreliable as a source of information on kunoichi or indeed anything related to Japan. If the above isn’t enough to prove that point, I also showed a few months back that several of Draeger’s historical claims about ‘ninja’ can be traced to a 1964 children’s book by Hatsumi Masaaki, which Draeger appears to have read uncritically and treated as if it were a primary source. Hopefully it’s obvious what that and the discussion above suggest about Ninjutsu’s degree of critical rigor and overall reliability.

To the extent that ‘ninja studies’ exists as an organized discipline in English, the fact that Adams and Draeger are two of the most widely-read and cited authors on the topic is a profound embarrassment for that field. Adams leans heavily on Okuse, Draeger more on Hatsumi, but both men’s books are similar in that their claims are unsourced, unreliable, and in quite a few cases literally unbelievable.

I’d also note that more recent English-language ‘ninja’ historians such as Stephen Turnbull, Anthony Cummins, and Kacem Zoughari have made no effort whatsoever to challenge this shit. These guys all have greater or lesser pretensions to academic respectability, but I’ve never seen any attempt from them to call out Draeger or Adams’s horrifically bad history for what it is. Just so you know, boys, this is what real scholars are supposed to do, to intervene in and provide correctives to the field, especially when it’s gone this far astray.

Anyway. Since we’re on the topic of the kunoichi and we’ve brought up Hatsumi Masaaki, we probably ought to note that he and his disciple Stephen Hayes had quite a bit to say about the kunoichi as well. So, in the interests of providing as complete a picture as possible of all the shitty history out there, let’s have a look at those guys next.

Using Worldcat I can identify editions published in 1971, 1973, 1980, and 1981 (tho apparently 1981 was a 6th edition), then 1989, 1992, 2008, and 2011, the last one of which I imagine was a 40th anniversary edition.

Draeger, Ninjutsu (my copy, 1989), p. 29. Emphasis mine.

Draeger, Ninjutsu, p. 54.

Draeger, Ninjutsu, p. 54.

Draeger, Ninjutsu, pp. 133. I would assume that the kanji for the name are 江田八郎, but who the hell knows. Needless to say, I can’t find any trace of a matching story using those kanji or any variants I can think of.