As a way of exploring the topic of the kunoichi, the supposed female shinobi, we’ve been working through Yoshimaru Katsuya’s 2017 book chapter “What is a Kunoichi?” You can bring yourself up to speed here and here if you missed the earliest installments, but Yoshimaru’s made two main arguments to date: 1) female shinobi didn’t exist, and 2) as purely fictional characters, their lineage stretches back to the Edo period.

Yoshimaru’s chapter now turns to the influence of the novelist Yamada Fūtarō (1922-2001) on the figure of the kunoichi. This influence, Yoshimaru notes, is considerable, so much so that some may think that Yamada invented the concept (he didn’t, as we’ve seen).1

Yamada Fūtarō is not very well known to Western audiences, even if they’re specialists in Japanese literature. I would wager that many of my academic readers have never heard of him, and I’m not aware of any sustained attempt to study his work in English. A graduate of Tokyo University’s med school, Yamada seems to have much preferred novels to practising medicine, and was extraordinarily prolific over the course of his career.2 The National Diet Library records contain nearly 2,000 entries for which he’s credited as author, for instance, and he carried on writing into his 80s.

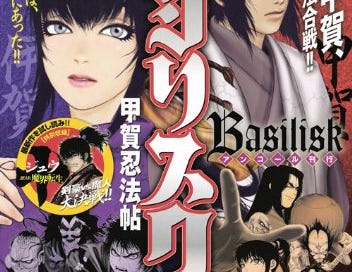

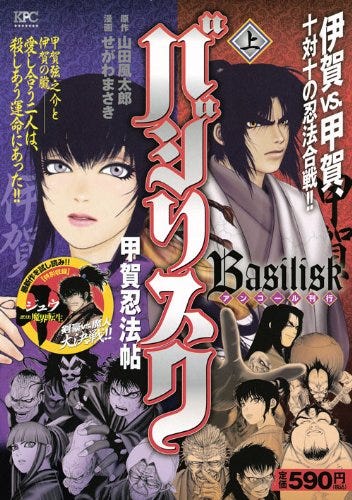

Basilisk: The Kōga Ninja Scrolls

Yamada was not a ninja novelist from the outset, though, starting his career from 1947 onward with a variety of works of historical fiction. His first ‘ninja’ work came in the shape of The Kōga Ninja Scrolls (Kōga ninpōchō, serialized from 1958-59), which features two teams of ninja from Iga Province and the Kōka region squaring off against each other in a FIGHT TO THE DEATH. This team includes several female ninja on both sides.3

The Kōga Ninja Scrolls is, to the best of my knowledge, the only one of Yamada’s many ninja novels that is available to Western audiences, in the shape of the anime and manga Basilisk. This is quite handy for our purposes, since it gives us visuals for some of the female ninja characters, such as Akeginu and Okoi, which tells us a certain amount.4 In this case, they are not realistic-type shinobi but still magic-using sorceress-type figures with various uncanny powers.

The female ninja character Okoi, for instance, can absorb an enemy’s blood through skin-to-skin contact, and according to the Basilisk Wiki, this is why she dresses in a revealing way, so as to expose as much skin as possible to the enemy. (No other reason, I’m sure). Some of these powers, as well as the depictions of the characters who have them, definitely seem to be pointing us forward to the idea of the seductress-assassin we’ve heard about in the supposedly historical lore.

But as Yoshimaru observes, in his 1958-9 Kōga Ninja Scrolls Yamada doesn’t refer to these characters as kunoichi, and in fact he wouldn’t use the term in that sense until as late as 1964. In 1960-61 Yamada published another novel entitled The Kunoichi Ninja Scrolls (Kunoichi ninpōchō), which you would think would be the point of origin for kunoichi as female ninja, but in fact Yamada doesn’t use the term that way in the story. The term used is onna ninja or ‘female ninja,’ while kunoichi within the book itself refers either to women in general or to male ninja magically tranforming into women.5

According to Yoshimaru, the first time that Yamada uses kunoichi to mean ‘female ninja’ is in his 1964 novel Ninja Arts: The Eight Dog Chronicles (Ninpō Hakkenden), where a character mentions a squad of female ninja known as the kunoichi shū.6 In December of that same year was released the film adaptation of Yamada’s The Kunoichi Ninja Scrolls, and it’s probable that this film title cemented the idea that kunoichi meant “female ninja” in the minds of popular audiences.7

Kunoichi Ninja Scrolls: That Old Vagina Magic

I want to step away from Yoshimaru’s discussion for a second here to make sure my readers understand how batshit insane the 1964 film version of Yamada’s Kunoichi Ninja Scrolls appears to be. Full disclosure: I haven’t seen it yet, as it’s a very difficult film to get hold of. I think I have finally succeeded in locating a DVD copy, however, and will post a review once I’ve got it and finished watching it.

Basically, the plot is that the bloodline of the late 16th century warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi is about to die out. The real-world Hideyoshi unified most of Japan but had only one surviving son, Hideyori, who was born very late in Hideyoshi’s life. This was kind of the downfall of the Toyotomi clan as a whole, since Hideyori would be too young to take control of the country after Hideyoshi died in 1598. Within about fifteen years Tokugawa Ieyasu had pretty much sewn up control of Japan, and then moved to get rid of Hideyori. This he did in the Winter and Summer Sieges of Osaka Castle in 1614-1615, and after the second one Hideyori took his own life, thus bringing an end to the Toyotomi clan.

This is where we find ourselves in the film; Hideyori is the last surviving scion of the Toyotomi, and if he dies, as seems likely, the clan will be extinguished. So naturally, the plan is to have five female ninjas have sex with Hideyori (obviously), and if all goes well this will result in the continuation of the Toyotomi bloodline. There’s an English-language review here, if you want to know more, but the key point is that the action on screen revolves around lots of sex, lots of magic, and lots of sex magic, some of which seems like a variation on the ol’ vagina dentata routine:

Every combat is done through the magic. To no one’s surprise, given the combatants involved, this almost always involves sex in some way. And the men always lose, though the maids also lose their magic power and die after each success. Some are lured into a deep well by a vision of scantily clad women, another has all his life fluids sucked out by the woman he sleeps with, a third actually gets stuck inside his victim and can not move away before he is killed.8

From what I can gather, the film is basically softcore ninja porn; English-language Wikipedia describes Kunoichi Ninja Scrolls as “a Japanese erotic film,” which probably tells you all you need to know.

So it was roughly late 1964, according to Yoshimaru, when the word kunoichi acquired a more-or-less stable sense as denoting a female ninja, as opposed to a man in disguise or a slang term for women in general. Obviously, none of this could possibly have been understood as making any strong historical claims; nobody in their right mind would mistake ninja vagina magic for actual history. In fact, probably the most consciously ‘realistic’ ninja novel of the early 1960s, Murayama Tomoyoshi’s Shinobi no mono series (pub. 1960-67), stated in its first volume that women couldn’t be shinobi because they’re too emotional.9 The historical claims would come from elsewhere, as I’ll cover in a subsequent post.

Kunoichi as Social Construct

So this is more or less where we end up. Kunoichi in the sense of female shinobi did not actually exist; they are entirely fictional constructs, who are postwar adaptations of earlier sorceress-heroine figures, and the term kunoichi itself is quite fuzzily defined until around 1964, when it acquires the cultural meaning it has today.

Why did the kunoichi emerge in the 1960s specifically? Yoshimaru has a few thoughts on this. One is that the kunoichi probably could not have emerged much earlier than that, given wartime Japanese censorship, which would not have looked favorably on such frivolous topics. One other possible factor - and here Yoshimaru acknowledges this is a bit off-the-wall - is that wartime Japan had seen Japanese women switch to wearing monpe work pants rather than full kimono all the time, and this perhaps had made it possible to imagine women as acrobatic action heroes - after all, it’s pretty hard to do ninja flips in a restrictive kimono.10

Another reason, though, is that the 1960s had seen a significant increase in women’s entry into the Japanese workforce; as the Japanese economic miracle began to kick in, there was more and more demand for labor, and it became increasingly common to see women working outside the home.11 This is the rise of the so-called ‘OL,’ or ‘office lady,’ a term that itself dates to 1963. So the kunoichi as female ninja emerges just as women are becoming more visible working alongside men, and in that sense, she’s kind of a bizarro reflection of women’s increased visibility and status in Japan - see, women can brutally murder people just as well as men can!

Except that, as in the real world, we don’t exactly get full equality. Yoshimaru observes that the kunoichi is often portrayed as less competent at the actual job of shinobi-ing than the men are, which I guess reflects the reality that the OL was a high profile phenomenon but rarely worked in any position of power or influence. Per Yoshimaru, this may well have to do with the fact that many ‘ninja’ novels were serialized in newspapers and weekly magazines for which the overwhelming majority of the audience were men. I imagine this would explain both the tendency toward tittillation and the need to make sure the kunoichi didn’t really challenge their male counterparts.12

Yoshimaru further notes that a good many of the 1960s kunoichi were also mother figures or defined by their ability to have children (like in the 1964 Kunoichi Ninja Scrolls), perhaps reflecting a sense that the kunoichi often ends up in the socially sanctioned role allotted for her of being a mother. More recent kunoichi, like those in Naruto, seem to skew younger, and perhaps are targeted at an audience of younger women as a form of wish fulfilment.13

So Yoshimaru’s piece is very helpful in two ways - first, making absolutely clear that the kunoichi was not an historical phenomenon, and second, adroitly locating them within a literary typology, as a kind of enduring archetype.

Like all worthwhile scholarship, however, “What is a Kunoichi?” also raises plenty of further questions. The most pressing one, I think, is fairly obvious: if there is no evidence for the existence of female shinobi called kunoichi, why are there so many books and internet articles claiming that they were a real thing?

This is what we’ll take on in the next post, then; and it won’t surprise you to know that we’re about to renew acquaintance with the usual array of bullshit merchants from the 1960s.

Yamada Fūtarō 山田風太郎; Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 185.

“Yamada Fūtarō” Nihon kindai bungaku daijiten (accessed thru Japan Knowledge, 11/4/2024)

Kōga ninpōchō 甲賀忍法帖; Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 184.

Akeginu 朱絹; Okoi お胡夷.

Kunoichi ninpōchō くノ一忍法帖; Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 185-6.

Kunoichi shū くノ一衆.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 185-6.

Quote from David Grote, “Female Ninja Magic / Kunoichi ninpo (1964),” pub. 04/12/2020. (https://japanonfilm.wordpress.com/2020/04/12/female-ninja-magic-kunoichi-ninpo-1964/)

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 186-87.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 189.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 188-89.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 189.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 190.