This series of posts has argued that ninja history makes a lot more sense if you understand it as a a form of creative literature that only appears to be making historical claims. In the next two posts I’d like to look at this aspect of ninja history from another angle, by showing how ninja authors have a marked tendency to present fictional events and individuals as historical ones.

You Really Shouldn’t Be Doing This

The basic idea here is easy to understand: it’s when a ninja historian writes about a fictional story as if it were something that had actually happened. You wouldn’t think this would be an issue, because it’s hard to think of a more fundamental mistake an historian could make. Imagine a study of 16th century Japan that referred in all apparent seriousness to Yoshii Toranaga instead of Tokugawa Ieyasu, for instance. Or, if you haven’t seen Shōgun, consider a history of early 20th century America that seemed to be under the impression that Charles Foster Kane was a real-life newspaper baron.

You might reasonably conclude if you came across such a passage that the writer didn’t know what the hell he was talking about. Unfortunately, this kind of howling error is far from a rare occurrence in English-language ninja histories.

Let’s look at a specific example. The below appears in Donn Draeger’s 1971 Ninjutsu and in Stephen Turnbull’s 1991 Ninja: The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult. It concerns the exploits of a supposed ninja called Kirigakure Saizō on a mission against the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi.1 Here it is, first in Draeger:

Kirigakure Saizō was a careless ninja. He trapped himself by a simple oversight. As he crouched silently one hot summer night under the floor of Kinoshita Tokichiro, a warlord he had been sent to spy on, Kirigakure was suddenly stabbed through the shoulder by the accurate thrust of a spear penetrating downward through the floor above him.

Kirigakure had neglected to notice the unusual activity of the mosquitoes that hummed noisily above him. But the lord’s alert guards in the room above Kirigakure had not missed this important telltale sign that told of human presence below the floor…2

And now as Turnbull tells it:

Other examples [of ninja assassinations] include Tokugawa Ieyasu’s sending of a ninja called Kirigakure Saizō to murder his rival Toyotomi Hideyoshi. Saizō hid beneath the floor of Hideyoshi’s dwelling, and a guard managed to pin him through the arm with the blade of his spear which he had thrust at random through the floorboards. Another ninja, presumably in the service of Hideyoshi, then smoked him out using a primitive flamethrower.3

The details each author has chosen to emphasize (mosquitoes, flamethrower, etc) are slightly different, but there’s no doubt we’re dealing with the same story here. In case you’re wondering, Kinoshita Tōkichirō and Toyotomi Hideyoshi are one and the same person; like a lot of Japanese warriors, Hideyoshi went by several different names during the course of his life.4 Turnbull seems to have been particularly fond of this story, because he repeated it in three further books published in 2003, 2005, and 2008.5

So as always when we come across a ninja story in an English-language work, we should start by asking: 1) What’s the source for this story? and 2) Is there reason to believe it’s true?

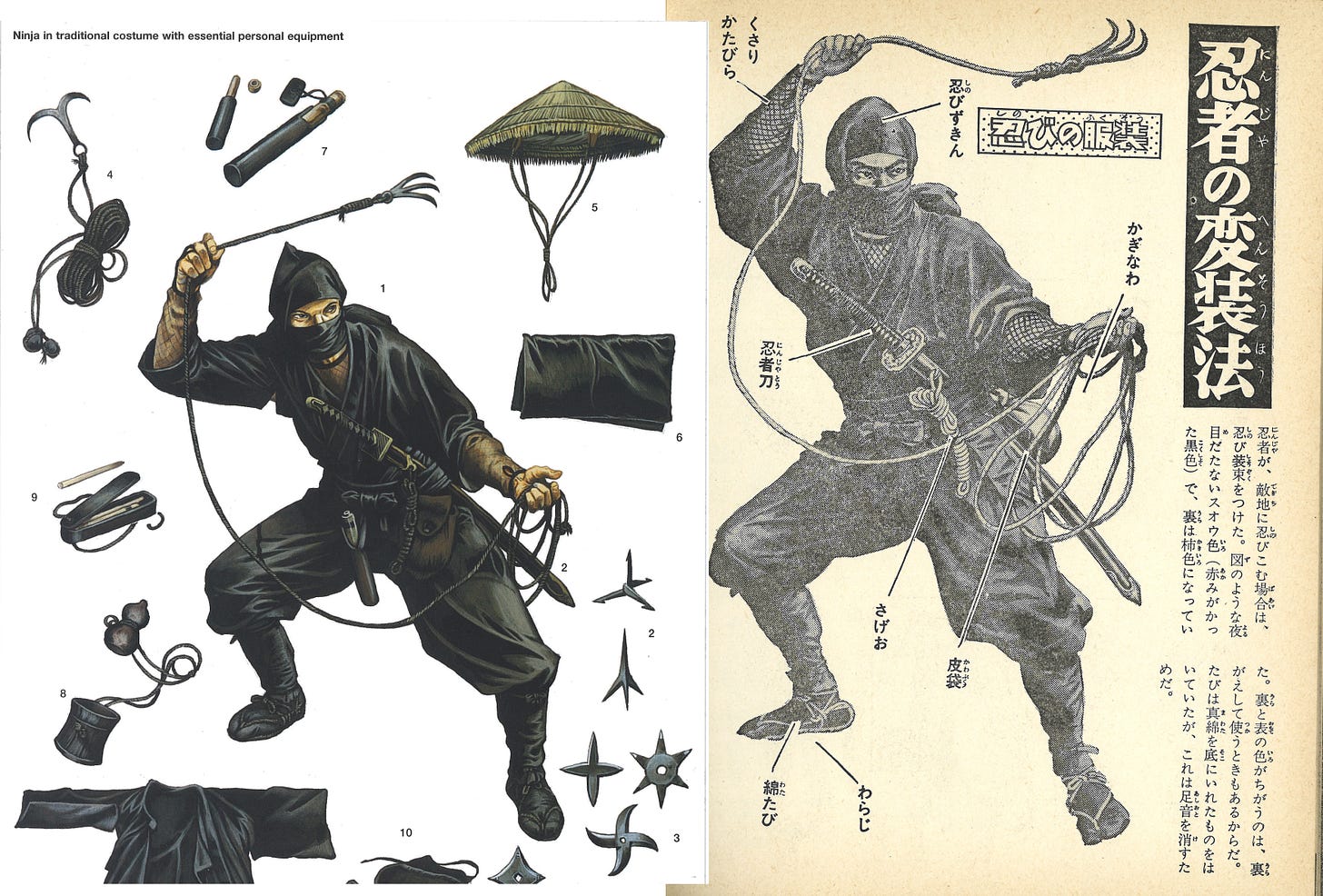

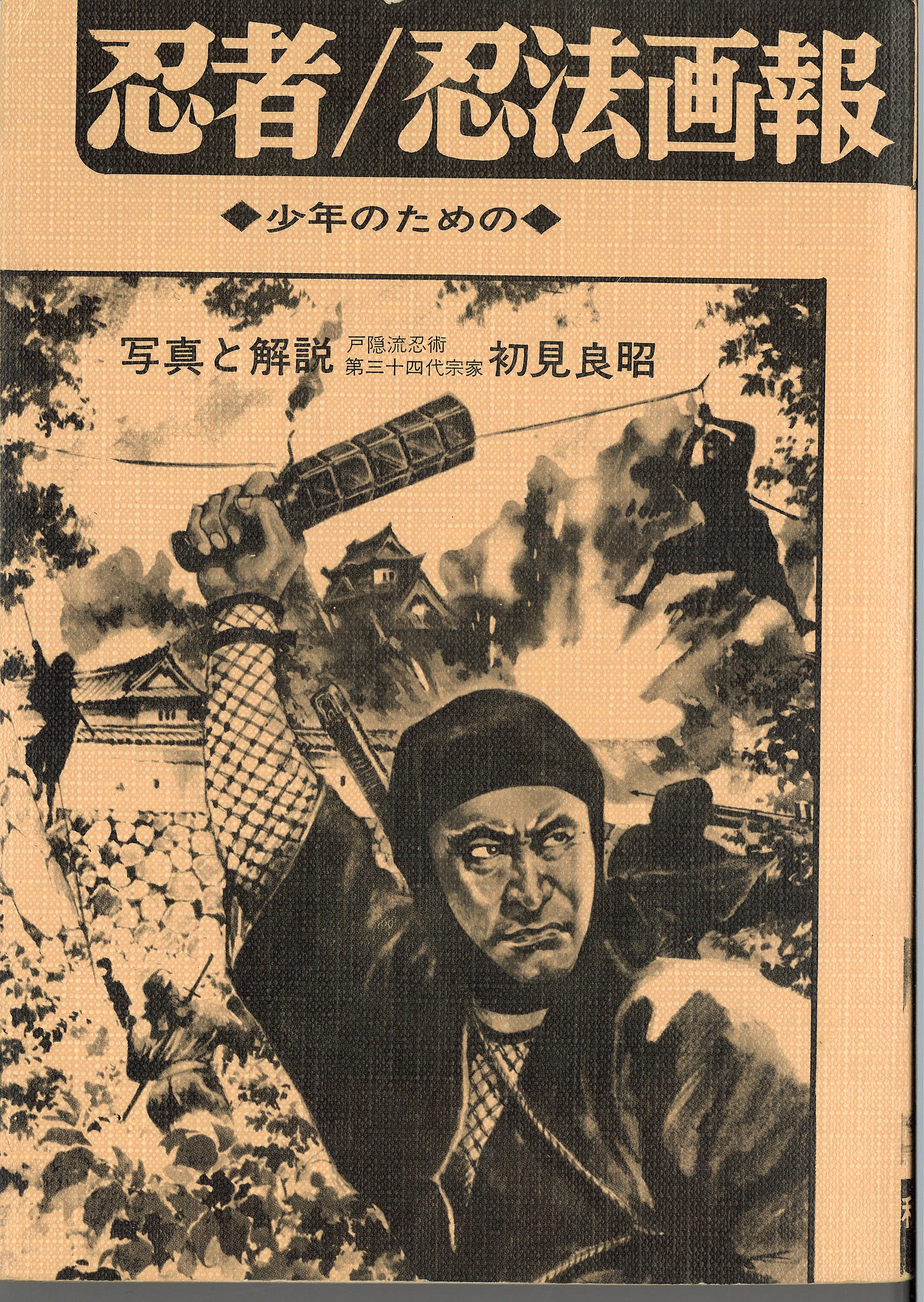

The source for the story in both cases is a book called Ninja and Ninja Skills Illustrated: For Kids, first published in 1964 by the ninjutsu master Hatsumi Masaaki.6 Here’s a scan of the front cover of my copy:

Ninja Skills Illustrated is a fun read with quite high production values, featuring lots of images of ninja in action, both realistic and cutesy-cartoonish. The last part of the book contains a long section of yomimono (stories, or ‘reading material’) of daring ninja missions set at various points in history.7 Among these yomimono is the Kirigakure Saizō story, which appears on pp. 150-152 of Hatsumi’s book and contains all of the details mentioned by Draeger and Turnbull, including the mosquitoes and the flamethrower.

Draeger’s Ninjutsu doesn’t have any citations or bibliography, which for the record you should treat as an immediate red flag for any ninja history going forward. This makes it challenging to figure out where Draeger was getting his information, but I think I can prove beyond reasonable doubt that Hatsumi’s Ninja Skills Illustrated was the source for many of his stories. Aside from the exact match between several of Hatsumi’s stories and those that appear in Ninjutsu, Draeger also appears to have copied a number of the illustrations that appear in Hatsumi’s book, as we see below:

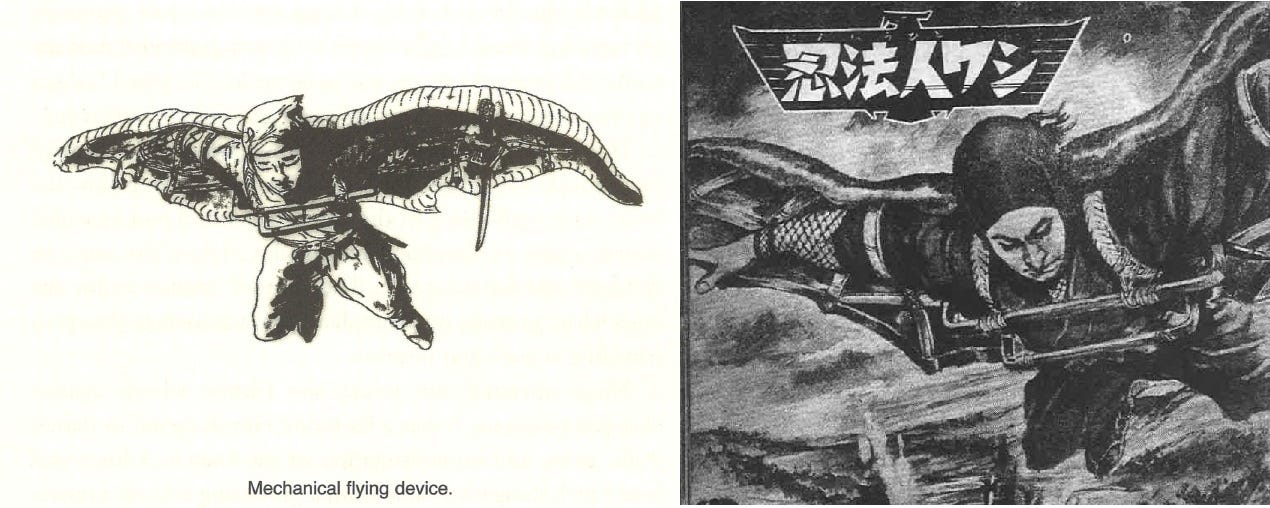

This is one of the illustrations for the Kirigakure Saizō story, with Draeger’s on the left (Ninjutsu, p. 110) and Hatsumi’s on the right (Ninja Skills Illustrated, p. 150). It’s not absolutely identical, but it’s pretty clear that Draeger’s illustration was adapted from Hatsumi’s original. Another example:

As the caption says, this is supposedly a mechanical flying device used by ninja. Again, the one on the left is Draeger’s (Ninjutsu, p. 99), and the one on the right is Hatsumi’s (Ninja Skills Illustrated, p. 111). The Japanese at the top on the right, in case you’re curious, says “Ninja Skills: The ‘Eagle-Man.’” There are several other similar examples of drawings in Draeger’s Ninjutsu adapted from Hatsumi, but I think we’ve made our case, so let’s move on.

As for Turnbull, since he cites Ninja Skills Illustrated in his notes and bibliography to his 1991 Secret Warrior Cult, the connection is pretty clear-cut, and it seems reasonable to assume that the source remained the same in his subsequent books.

So it seems pretty clear that Hatsumi’s children’s book Ninja Skills Illustrated was a significant source for both Turnbull and Draeger, and as far as I can tell it also appears to have been their only source for several of the ninja stories that appear in both books. If either author ever identified an original Japanese-language source for their stories other than Hatsumi, neither of them mention it. Since my own search for an original source for the Kirigakure Saizō story other than Hatsumi has so far come up empty, I’m forced to conclude that Hatsumi’s book was the only source both authors used.

This is where we run into our first problem, which is that a serious historian should not be using a children’s book as their only supporting evidence for an historical claim. This much, I would hope, is non-controversial. It’s not hard to tell that Ninja Skills Illustrated is a children’s book, by the way; if the kawaii ninja pictures inside weren’t enough of a clue, the book has the words “For Kids” (shōnen no tame) on the front cover, and when the main text begins its first sentence runs, “When your mommies and daddies were themselves children…”8

I want to just pause for emphasis here and let that sink in. Two of the most influential English-language ninja writers of the last 60 years were using a children’s comic book as one of their main sources.

Remember, Draeger’s book was in print through multiple editions between 1971 and 2011, while Turnbull’s works have been the main point of reference on the ‘ninja’ for general English-language readers over the last 30 years or so.

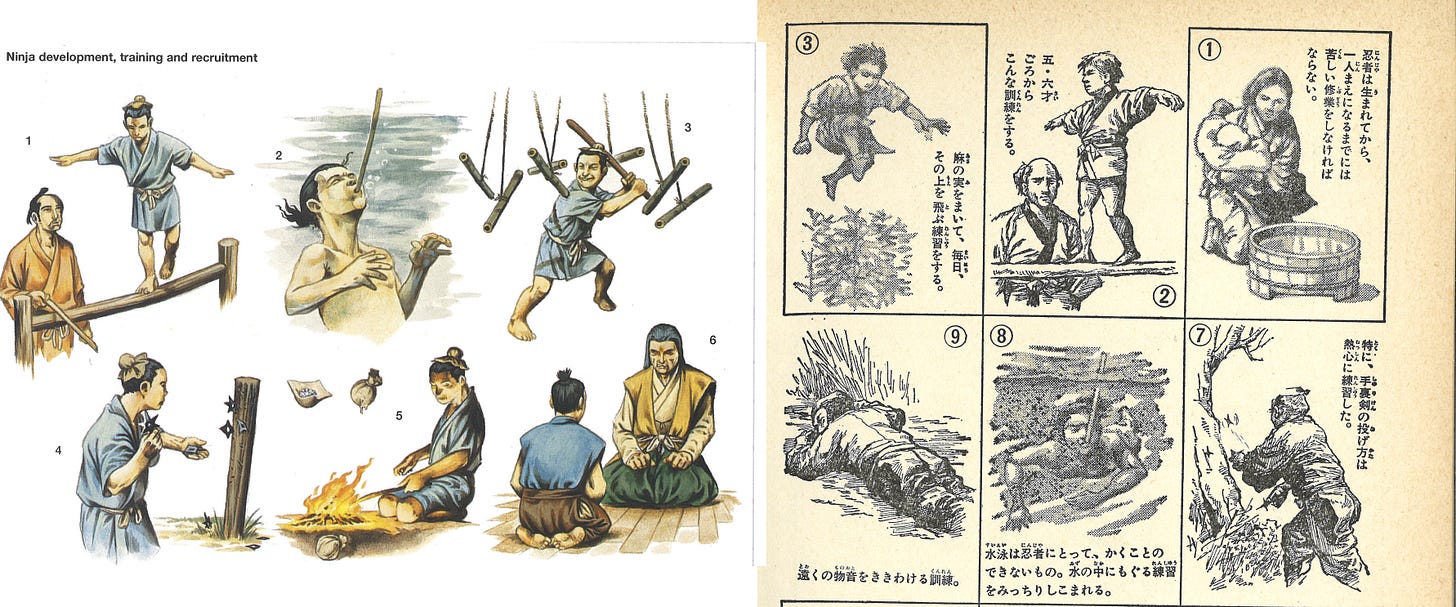

Turnbull appears to have continued using Hatsumi’s book into the 2000s, incidentally, as suggested by some of the illustrations that appear in his 2003 Ninja: AD 1460-1650:

Left is Turnbull (p. 33/‘A’), right is Hatsumi (p. 31).

Same again: Turnbull (2003, p. 34/‘C’) on the left, Hatsumi (p. 32) on the right. The illustrations are not exactly the same, but you can see pretty clearly where Turnbull adapted them from, especially the boy balancing on a beam (top-middle in Hatsumi), the guy breathing underwater (bottom-middle), and the one throwing shuriken (bottom-right).

But Wait. It Gets Worse.

OK, look – maybe it’s kind of embarrassing for Turnbull and Draeger to be using a children’s book as their main evidence to support their historical claims, and yes, we can agree that they probably shouldn’t have done that. But the fact the Kirigakure Saizō story appeared in a children’s book doesn’t mean it isn’t true, right?

Fair point. Allow me to refer you to p. 37 of Hatsumi’s Ninja Skills Illustrated:

The ninja Sarutobi Sasuke is in fact a fictional creation, and in the same way Kirigakure Saizō was not someone who actually existed.9

Ah.

Let me remind you that the above quotation is from Draeger and Turnbull’s own source.

If you’re going to use a children’s book in place of primary sources, at least read the damn thing.

The most charitable interpretation here is that Turnbull and Draeger were simply sloppy and credulous, in that they were using a work that should never have been their sole source, they didn’t read it carefully enough to realize its limitations, and they don’t seem to have confirmed the existence of an original source for Hatsumi’s story. That assumes that there is one and the story isn’t simply Hatsumi’s own invention.

In partial defense of Draeger, he does at least preface the collection of stories in which Kirigakure Saizō appears by noting that some of his stories are fictional (although as I pointed out here, he doesn’t tell the reader which ones, which makes his warning fairly unhelpful). But there’s no indication in Turnbull’s 1991 Secret Warrior Cult that the story is anything other than factual, nor is there any such indication in Turnbull’s three subsequent re-tellings into the 2000s. It seems very likely that the majority of Turnbull’s readers would have come away thinking that the Kirigakure Saizō episode was established historical fact and yet more evidence for the reality of the ‘ninja.’

I wish this was the only such example, but as I’ll explore in the next post, it’s far from an isolated case even in Turnbull’s work.

Perhaps now, dear reader, you are beginning to understand the true scale of the problem, and why I have written that “almost everything in English on the ‘ninja’ since 1960 is garbage.”

Kirigakure Saizō 霧隠才蔵. Literally, the name would seem to mean “Saizō, Hidden-By-Mist.”

Donn F. Draeger, Ninjutsu (1989), pp 109-111.

Turnbull, Secret Warrior Cult (1991), p. 54.

Kinoshita Tōkichirō 木下藤吉郎; Toyotomi Hideyoshi 豊臣秀吉. The original source has Kinoshita, in case it matters. Turnbull’s correction to Hideyoshi here is completely reasonable under the circumstances.

Ninja: AD 1460-1650, p. 32; Warriors of Medieval Japan (Osprey Books, 2005), p. 180; and his Real Ninja (Enchanted Lion Books, 2008), pp. 33-34. The last one is a children’s book, but still.

Shōnen no tame no ninja, ninpō gahō 少年のための忍者・忍法画報, published by Akiyama Shoten. I think the first printing was 1964, and while the copy I have doesn’t have a colophon with date or publishing information, I believe it’s a later 1977 edition.

Yomimono 読みのも.

Hatsumi, Ninja Skills Illustrated p. 10. Turnbull’s rendering of the title of Hatsumi’s work in the bibliography to his 1991 Secret Warrior Cult leaves out the “For Kids” (shōnen no tame no) part of the book’s title. There could be several reasons why he did that - he may not have thought it was part of the book’s full bibliographic title, for instance - but the result is that even a Japanese speaker who surveyed Turnbull’s bibliography might well have failed to realize that it was a children’s book. There can’t really be any argument about this, by the way; the word shōnen isn’t always clearly defined in terms of age range, but the Dejitaru Daijirin dictionary notes that it normally denotes children from the ages of roughly 7-8 to the ages of 15-16.

Hatsumi, Ninja Skills Illustrated p. 37; bolding mine, obviously. “Fictional creation” is 作り話; “not someone who actually existed” is 実在の人物ではなかった。