Every Little Thing She Does is Magic

Looking for the Roots of the Kunoichi with a Bunch of Fictional Sorceresses

Last time around we introduced Japanese scholar Yoshimaru Katsuya’s arguments that kunoichi, the supposed female shinobi, were not a thing. We also saw that the word kunoichi itself seems to have been an obscure slang term for ‘woman’ in general, not for female shinobi.

Since kunoichi didn’t exist, there’s only one place to go, and that’s into the realm of fiction.

I Got the Magic in Me

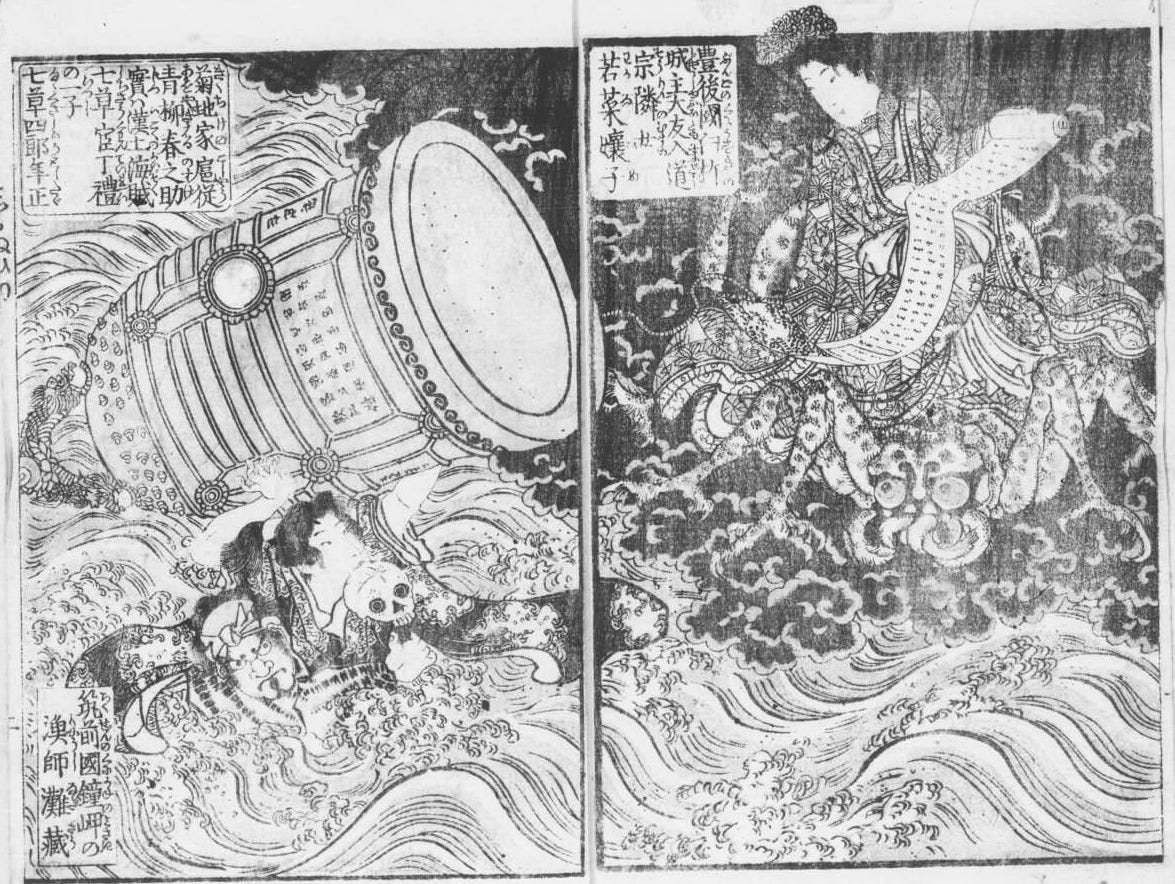

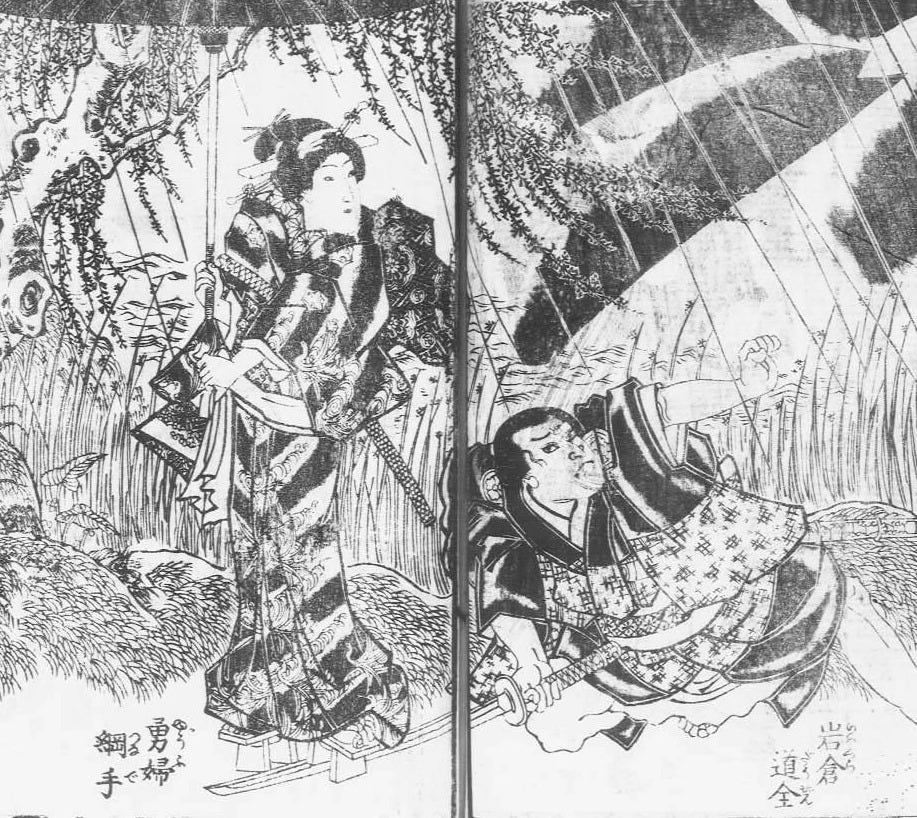

A lot of Yoshimaru’s discussion from this point onward covers what we might now think of as action heroines in early modern and modern Japanese fiction. There’s actually quite a few such characters, like Lady Tsunade, a sword-wielding, magic-using, butt-kicking character in the very popular series Jiraiya.1 Fans of the anime Naruto will know Lady Tsunade as a kind of combined mother/boss/teacher/sex object figure, but the original character can be traced back to the early 19th century:

Now, if you’re looking at that picture and thinking, “That doesn’t exactly scream ‘female ninja,’” you’re not alone. Yoshimaru would agree with you, writing that “based on their appearance, one does not get the sense that these figures are shinobi.”2

What Yoshimaru is doing is trying to establish a kind of lineage of magic-using female action heroines that’s going to extend into the postwar, where the kunoichi will first start to take on the form we’re now familiar with. What’s holding the lineage together conceptually is the use of shadow magic, or in Japanese, ninjutsu.

This requires we stop for a second to explain a fairly important linguistic shift in the history of the ‘ninja.’ Right now, in 2024, most readers understand the term ninjutsu to mean either the techniques of the historical shinobi or the postwar martial art that Hatsumi Masaaki developed, which is supposedly based on the same. There’s a school teaching martial arts-type ninjitsu [sic] not too far away from me in Scottsdale, Arizona, for instance.

The thing is, though, that as late as the mid-1960s the term ninjutsu in Japan was more commonly understood to mean literal magic, doing stuff like turning invisible, flying, or controlling animals.3 So this is what Lady Wakana is doing in the print up at the top - she’s using magic to fly.

As you might expect, these co-existing meanings of the term ninjutsu were easy to exploit for 1960s ‘ninja’ historians, who claimed either that the fictional magical powers were based on the amazing real-world physical skills of the historical shinobi, or just pointed to mentions of magic-type ninjutsu in earlier texts to ‘claim’ certain fictional characters as having been ‘ninja,’ and thereby prove that their newly-developed concept actually had a long history.4

I think the first claim, that fictional magical powers must have a real-world correlate, shows a fundamental misunderstanding of the nature of fiction. My read is that it’s probably the other way around, that the historical claims were inspired by the fictional characters. The second argument also seems obviously ahistorical and anachronistic, which is why I’ll generally translate ninjutsu in a magical context as ‘shadow magic.’ Doing that seems more accurate and less likely to lead to confusion, because God knows we’ve got enough of that in ‘ninja’ studies already.

Everything She Do Just Turns Me On

So although characters like Ladies Tsunade and Wakana above are magic-using action heroines, they’re not really kunoichi in the sense that we understand the term. There are characters in novels through the 1920s who are female users of shadow magic and even trained warriors, but these characters, Yoshimaru argues, don’t have many of the elements of modern ‘ninja’-ness that we’d look for - they’re more general warrior archetypes than obvious shinobi.

In Yoshimaru’s view, the first character who is really close enough to be called a female ‘ninja’ doesn’t appear until 1948, in the serialized novel Sarutobi Sasuke by Tomita Tsuneo (1901-1967).5 There’s an image of the cover here, if you’re interested, which depicts the character in question, a woman named Okame. Yoshimaru notes that in wartime Japan, frivolous topics such as shadow magic would have been frowned upon, as would anything too sexy, but Tomita’s work clearly benefited from the lifting of restrictions, because Okame is portrayed in pretty racy terms for the time. Yoshimaru notes one section in particular, where a disguised Okame fights and is defeated by the titular hero Sarutobi Sasuke on a riverbank:

Sasuke became aware of how pale his opponent’s skin was. The hood had come off in the fight and the hair had come loose, the black strands gently floating out into the water as if it were some plant that grew therein, drifting out along with the current. Sasuke saw the swelling of small yet well-formed breasts at the ninja’s chest. The woman was clad in only a single layer of robe, and her struggling, palely feminine, pliant flesh was now trembling alluringly beneath his own body as he held her down.6

Of this passage, Yoshimaru comments, laconically, “One gets the sense that Tomita’s Sarutobi Sasuke presupposed that its audience was adult men” - as opposed to the generally teenage audience for previous ninja novels.7 In the sense that the kunoichi is often an object of sexual desire, Yoshimaru’s point about Okame being arguably the first kunoichi is well taken.

There are a few more examples of similar magic-using female ‘ninja’ in novels from the early fifties, including works by historical novelist Yoshikawa Eiji (1892-1962), which I kind of expected, and noted feminist author Hayashi Fumiko (1903-1951), which I certainly didn’t.8 (I think a lot of professional scholars of Japanese literature might be genuinely surprised by how many well-known, canonical authors wrote ‘ninja’ novels, mostly because academics tend to ignore ‘ninja’ stuff in general.)

It’s not until 1956-58 or so that we see the first appearance of the word kunoichi in a Japanese novel, in Gomi Yasuhiro’s (1921-1980) Warrior Tales of the Yagyū Clan (Yagyū bugeichō).9 In this novel there’s a mention of kunoichi no jutsu, or ‘kunoichi magic,’ but this doesn’t refer to a female shinobi as we might expect. Rather, in this context, kunoichi no jutsu means a male ninja magically transforming himself to take on the appearance of a woman, not a female shinobi as such.10 So it’s clear that here kunoichi just means ‘woman,’ because kunoichi magic means transforming yourself into a woman.

What Yoshimaru is finding is that even as late as the late 1950s, just as the postwar ‘ninja’ boom was beginning, there wasn’t necessarily a cultural consensus as to what kunoichi actually meant or how the term should be used. This seems to be confirmed in another novel, Shiba Ryōtarō’s widely-praised ‘ninja’ novel Castle of Owls (Fukurō no shiro, 1958-9; there’s a 1963 film adaptation, apparently), in which kunoichi is simply a shinobi slang term for ‘women’ in general.11

It wouldn’t be until the early to mid-1960s, in fact, that kunoichi came to be fully established as meaning “female shinobi.” That process owed a lot to the prolific pulp fiction author Yamada Fūtarō (1922-2001), so it’s Yamada’s work we’ll look at in our next post.12

Oh, and in case you need a reminder: at no point in any of the above have we left the world of fiction - it’s novels all the way down.

Lady Tsunade 綱手姫;Jiraiya 児雷也.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 170. Japanese: 外見から「忍び」らしさを感じ取れない.

It seems that 1960s ‘ninja’ historians often had to explain this to their audience, that they didn’t mean ‘magic’ when they were talking about ninjutsu. For examples of this point being made, see Hatsumi Masaaki, Ninja ninpō gahō (1964), p. 10; Ogawa Tōru, “Ninja wa teikōsha tarienu ka” Eiga hyōron 20-2 (January 1963), p. 19; and Yamamoto Satsuo, Watakushi no eiga jinsei (Shin Nippon Shuppansha, 1984), pp. 212.

See e.g. Stephen Turnbull, Ninja: AD 1460-1650 (2003), p. 4; Hatsumi Masaaki, Ninja ninpō gahō, p. 37.

Sarutobi Sasuke 猿飛佐助; Tomita Tsuneo 富田常雄.

Quoted in Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 176. Japanese: 佐助は相手の肌の白さを感じた。頭巾を失った髪がほぐれ、黒髪が水藻に似てなよなよと水中にたゆい、そして長く流れた。佐助は忍者の胸につぶらな実を持った乳房のふくらみを見た。今は単衣一枚となって、もがく、女性の白く、なめらかな肉体が組み敷いた彼の体の下で妖艶にゆらいで居た。

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” p. 176-77. Japanese: 富田常雄『猿飛佐助』は成人男性の読者を想定すると思われる。

Yoshikawa Eiji 吉川英治;Hayashi Fumiko 林芙美子.

Gomi Yasuhiro 五味康祐;Yagyū bugeichō 柳生武芸帳;Kunoichi no jutsu くノ一の術.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” pp. 179-181.

Yoshimaru, “Kunoichi to wa nani ka,” pp. 181-2. Shiba Ryōtarō 司馬遼太郎;Fukurō no shiro 梟の城.

Yamada Fūtarō 山田風太郎.