Writing History, Writing Fiction

Part 1: You Know What They Say About Facts and a Good Story...

When I started this newsletter, I began it with the argument that the ninja is better understood as a literary construct rather than an historical one. We’ve taken a look at the historical evidence, so now it’s time to look more closely at how ninja history is generally written and presented. I want to do this because there are certain aspects of ninja history that are aberrant or even bizarre by the standards of academic history, but which start to make sense if we understand ninja history as a creative literary endeavor instead.

In today’s post, I’d like to introduce what I think will be a useful idea for understanding ninja history, which is the concept of unacknowledged historical fiction.

How to Make Things Up and Get Away With It

We tend to think of the depiction of historical events as falling into one of two categories. The first, simply, is history – a narrative of things that we understand to have happened, based on documentary or other kinds of historical evidence. To pick two examples at random from books within arm’s reach of me right now, we might offer Mary Elizabeth Berry’s biography of the 16th century warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi, or Eric Larson’s Dead Wake, an account of the sinking of the steamship Lusitania in 1915. The reader understands these works to be making a claim to truth, to be describing things that happened and the real actions of people who existed, and to be based on some kind of historical evidence.

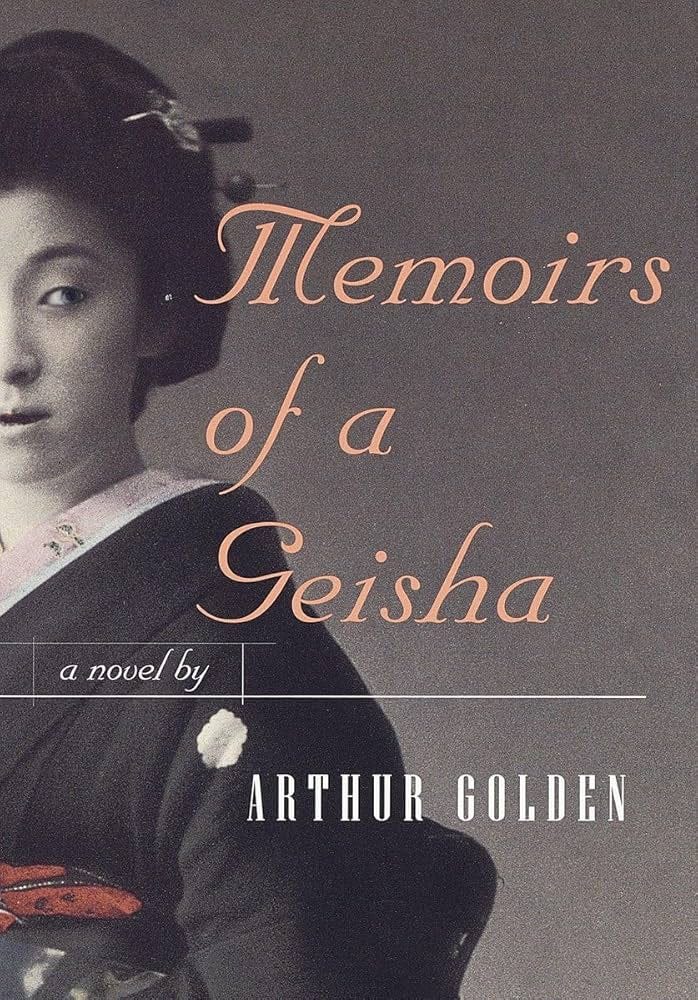

The second category is historical fiction, where the setting may include things that actually happened and people who existed, but where the main story and the main characters are acknowledged to be made up for the purposes of good story-telling (though they may be ‘based on’ real people). Into this second category would fall things like the novel and TV adaptations of Shōgun, Tom Cruise’s Last Samurai, Memoirs of a Geisha, and so on. In the case of historical fiction, the reader is aware that the work is about telling a good story first, and that historical accuracy is a secondary concern.

What I’ve read of ninja histories leads me to suggest we should also think in terms of a third category, that of unacknowledged historical fiction. Put simply, unacknowledged historical fiction appears to the reader to be regular history, a narrative where the things we read about are supported by historical evidence. In fact, though, with unacknowledged fiction a substantial part will be derived not from primary source evidence but from other explicitly fictional sources or from the imagination of the author.

The key distinction between unacknowledged historical fiction and regular historical fiction is that with regular historical fiction the author makes things up, but the reader knows that. With the unacknowledged version, the author makes things up but does not openly acknowledge that he is doing so. In fact, unacknowledged historical fiction quite often claims to be a “true story” or appears to follow standard historical practice in making reference to primary source evidence.

It obviously follows that unacknowledged historical fiction brings up some pretty big ethical problems. For one, since it’s not clearly acknowledged as fiction, it carries a high risk of misleading general audiences, who, by definition, don’t have the background to assess what is backed by historical evidence and what is not. In fairness, this can happen with regular historical fiction as well. Even though it’s explicitly stated to be a work of fiction, the novel Memoirs of a Geisha has shaped a lot of people’s impressions of real-life geisha and their culture in Japan. Part of this has to do with author Arthur Golden’s literary technique, by the way; the novel is framed very convincingly, as if were a memoir told by a real geisha and translated by an American academic.1

It’s true that the general reader of a historical novel such as Memoirs of a Geisha may not know precisely where the boundary between history and fiction lies, but she is at least aware that there is one. This would be why a lot of us in Japan Studies have been getting the question “How accurate is Shōgun?” over the last six months. But this is not the case with unacknowledged historical fiction, and that creates real potential to mislead.

It seems to me that unacknowledged historical fiction is most likely to happen when a writer wants to tell a good story but finds that the historical evidence isn’t there or isn’t very interesting, and the writer then feels the need to sex up their material beyond what’s in the primary sources. This, I think, is what has happened with a lot of ninja histories. We’ve explored previously how there is some textual historical evidence for the notion of shinobi as a role in warfare in late medieval Japan. But as we have also seen, there isn’t very much of that evidence, and what there is doesn’t tell us all that much. From the point of view of the historian, the meager evidence is a limitation and a reason for caution, as you are very restricted in what you can reasonably say about shinobi based on the evidence. For the writer of historical fiction, and particularly for the writer of unacknowledged historical fiction, though, this is an opportunity – you can invent all the details of the shinobi to your heart’s content, and make your shinobi do whatever you think ‘ninja’ would have done.

Okuse Heishichirō: The Man, The Myth

Let me introduce you now, gentle reader, to a man by the name of Okuse Heishichirō.

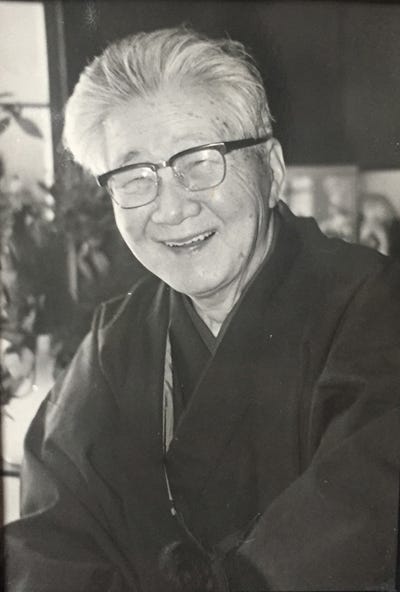

Okuse is an important name in ninja circles from the late 1950s onward, as he was one of the most prominent advocates for the modern ‘ninja’ as we understand the term today. Okuse was not exactly a disinterested party, as he was for many years the mayor of the town of Ueno in modern-day Mie Prefecture.2 Located in central Japan, modern Mie overlaps with part of the old Iga Province, widely believed to have been the heartland of the historical shinobi. Okuse’s ninja writings were undeniably good for tourism in Mie Prefecture, and he was the founding director of the Iga Ninja Museum in Mie that remains popular to the present day.

I’ll have a lot to say going forward about Okuse and his faults as an historian, but for now I want to focus on an interesting exchange from the mid-1960s between Okuse himself and three Japanese scholars, Adachi Ken’ichi, Ozaki Hideki, and Yamada Munemutsu.3 These latter three had published a book entitled “Why are People Nowadays so into Ninja?,” which apparently had come into Okuse’s possession.4

One part of this co-authored book seems to have really annoyed Okuse, specifically a section where Adachi, Ozaki, and Yamada wrote that they had looked at the historical record of ninjutsu and found it trivial and not very interesting (tsumaranu). In their view, the fiction had taken on a far greater importance than the relatively boring truth. Not only that, but that ninjutsu discourse was so full of untruths (uso) that it was very difficult to tell what was true and false in the first place.5

I’m not sure if these comments were directed at Okuse, but he certainly seems to have taken them personally,6 and his response in his 1964 book Ninja Arts: Secret Teachings and Real Examples is worth quoting directly:

I am one who seeks the realm of truth that may be found on the other side of falsehood. I have never said that every page and every word of the written [ninja] lore is true. From the moment I began my studies, I have ruthlessly pared away all of the falsehoods that lie on the other side of the truth in the written lore, as well as the falsehood in the traditional spoken lore. I have sought to establish such a ninjutsu, stripped of any and all falsehood, as a real phenomenon that stands in opposition to its false counterpart. If I were to put the real and the false phenomena side by side, then throw away anything that I judged was uninteresting while at the same time making a show of great interest in the details of the true historical phenomenon – I cannot go along with such a dilettante, conflicted idea of ‘ninja arts’ (ninpō).7

The repeated emphasis on “truth” and “falsehood” is in the original, by the way. I’m not one for amateur psychology, but you’d have to say a nerve had been touched there. It also strikes me that the last line of this paragraph, starting with “If I were to put the real and the false…” is a pretty good summary of what the writer of unacknowledged historical fiction might do.

So Okuse was insistent that he was doing good history, rigorously separating the truth from the lies, and yet…he wasn’t. My own assessment of Okuse’s writing would be that he was definitely not as scrupulous an historian as he suggests here, and that he absolutely would bend the facts if he thought it would make a more compelling story. It’s not just me, either. Yamada Yūji, one of the lead researchers of the recently-founded Mie University Ninja Research Center, described Okuse’s work as follows in a 2018 address:

Okuse Heishichirō’s research certainly advanced the study of the ninja, but in his work there are parts that are, shall we say, highly literary, or which are also about telling a good story; from our present-day perspective, I think there are a lot of parts that have problems in terms of historical evidence.8

Yamada is being more diplomatic than I would be, but his point is clear – Okuse was above all interested in telling a good story, and it was much less important to ensure he was presenting accurate history.

The reason that this matters is that Okuse was one of the most prominent and influential ‘ninja’ advocates of the 20th century. He wrote numerous books and pamphlets on the topic, which early English-language ninja writers would rely on as source material, most notably in Andrew Adams’ widely-read Ninja: The Invisible Assassins (first pub. 1970). So Okuse is someone whose impact on ninja history is undeniable, yet in my judgment, and in Yamada’s, too, he’s completely unreliable as an historian.

In the next few posts, we’ll consider how this notion of unacknowledged historical fiction can explain an awful lot about ninja history in the 20th century and 21st century.

Compounded by the fact that a non-zero number of English-language readers are under the misconception that “novel” is another word for “book.”

Ueno-shi 上野市;Mie-ken 三重県; Iga Province 伊賀の国.

Adachi Ken’ichi 足立巻一 (1913-1985); Ozaki Hideki 尾崎秀樹 (1928-1999); Yamada Munemutsu 山田宗睦 (1925-2024). Interestingly, Adachi and Hideki were literary scholars while Yamada was a philosopher, suggesting that literary scholars have perceived what’s up with ninja discourse right from the start.

Ninpō: gendaijin wa naze ninja ni akogareru ka 忍法・現代人はなぜ忍者にあこがれるか (San-Ichi Shobō, 1964).

As summarized in Okuse, Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei 忍法・その秘伝と実例 (Shinjinbutsu Ōraisha, 1995), p. 307. The book was first published in 1964, but my copy is a newer 1995 edition.

I’m not 100% sure because Gendaijin wa naze ninja ni akogareru ka has proven very difficult to get hold of; there don’t seem to be any copies in US libraries, and while I would normally ask ASU’s libraries to buy a copy, right now ASU’s Asian librarian position is vacant. In the meantime I’m dependent on Okuse’s quotation and/or summary of what it says. I’ve ordered a copy myself, and when it arrives, I’ll update the post if the contents of the book are significantly different than what Okuse implies.

Okuse, Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei p. 307.

Yamada Yūji, “Ninja kenkyū no konjaku” 忍者研究の今昔 [Ninja Studies Past and Present] in Ninja kenkyū [Ninja Studies] Vol. 1 (August 2018), pp. 31-32. Japanese: “shall we say, highly literary” 非常に文学的というか; “about telling a good story” 面白味を兼ね添えた; “have problems in terms of historical evidence” 史料的に問題がある.