This newsletter is about ninja.

If you’re reading this, you probably have at least some idea of what a ninja is. If you’re into Japanese history, you probably have an idea of ninja as a group of shadowy assassins in medieval Japan, terrifying their enemies with their ability to reach even the most well-protected target. If you’re more of a film buff, maybe you hear ‘ninja’ and think of Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, the Japanese anime Naruto and Ninja Hattori-kun, or schlocky martial arts movies like Menachem Golan’s 1980 Enter the Ninja.1 Or, if you’re into training in the martial arts, you probably think of ninja as the historical practitioners of the martial art of ninjutsu, as popularized in the second half of the 20th century by Hatsumi Masaaki, Stephen Hayes, and various others.

I am, as it happens, a practicing academic with a focus on Japanese literature and history, and a few years ago, one of my students said to me after class, “My brother says that ninja were more honorable than samurai, but I think he’s wrong. What do you think?”

I didn’t really know how to answer that question. I knew that the ninja was one of the most recognizably Japanese pop icons – obviously – but I also realized that I didn’t know that much about the topic myself, nor did I know where to send the student for some reliable information on the topic. So I figured I’d better educate myself. I ordered the first few English-language books on ninja I could find, mostly the first stuff that came up on Google Books. Using that as a kind of starting point, I took a look at the conventional wisdom on the ninja.

That was when I realized we have a problem.

Reading as an academic, it was obvious that these books were really, really bad. A few appeared to be written by authors with little or no expertise in Japanese history or Japanese language ability, and even the better ones had clear problems of evidence, argument, and citation. Over the next few years I kept on picking up more and more books on the ninja, mostly in English but also quite a few in Japanese, to see if I could find something that was actually worthwhile and that I could assign to my students. I didn’t really find anything, at least not in English, and started to get more and more annoyed at what I was reading. I also started doing some source-checking, to see if I could verify some of the claims of ‘ninja assassinations’ and the like. Even though the existing ninja literature usually doesn’t cite its sources, I was able to track down the source for the claim in many cases, and much of the time the evidence just didn’t support what the author was claiming.

So you need to know, dear reader, that almost everything written on the topic of the ninja in English since 1960 is garbage. This is not immediately obvious, because quite a few ninja books appear superficially convincing and well-researched, or are produced by writers who genuinely do have bona fide credentials as experts on Japan and Japanese culture. I’m thinking here mainly of writers like Stephen Turnbull, who has a PhD in Japanese religions and has written at least five ninja books that I’m aware of since 1991,2 or Kacem Zoughari, who has a PhD from INALCO, one of France’s best universities for Asian studies.3 But even the most seemingly scholarly books on the topic in English can turn out, on closer examination, to be horribly unreliable, in the sense that any ‘ninja’ event the author is describing might well have no basis in historical evidence. What we’ve got is a ninja-related epistemological crisis – the entire knowledge structure underpinning the history of the ninja is completely broken, so much so that we can’t be sure that any specific claim about the historical ninja can be trusted. Since these same published books are usually the source for most of the claims about ninja that appear online, especially on Wikipedia, they’re basically the bedrock for knowledge about the ninja in English.

I think the English-speaking public has been really poorly served by what has been produced over the last sixty years on the topic of the ninja, and this newsletter is my way of doing something about it.

So this newsletter will look at ninja culture from two main angles. The first is basically historical, in that I’ll be taking a deep dive into a range of historical claims about the existence of ninja (or shinobi, to use the term that the more clued-in advocates prefer) and critically assessing them.4 Right off the bat, I want to declare my biases: as someone with formal academic training in Japanese history and literature, I am deeply skeptical of many of the claims made about the historical shinobi. As I noted above, the English-language literature for the most part is just terrible history, featuring dubious claims, flawed methodology, problems of evidence and citation, plagiarism, internal incoherence, and tons of other issues. These problems have rarely been publicly noted, much less corrected, and the result is several shelves full of popular books that are horribly misleading on many aspects of Japanese history and culture. Though it is slightly better in some respects and has improved dramatically in recent years, the Japanese-language material also has a lot of endemic problems, which I’ll discuss at some length.

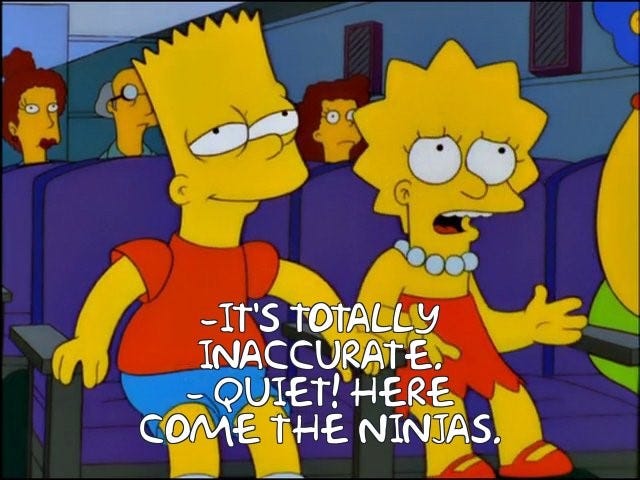

The bad history, then, is one angle. The second angle, though, acknowledges something we all know to be true: ninja are awesome. Here, I’m going to let my inner fanboy out and have fun with the ninja in popular culture, considering why and how the ninja appears from the early 1960s in both Japan and the English-speaking world, and what we can learn from studying the ninja in crappy movies, novels, and any other form of media in which he (or sometimes she) appears. In other words, the other side of the newsletter is basically literary and movie criticism, in which I’m not particularly concerned with whether the movies are ‘accurate’ or not, because the question doesn’t really make sense in the first place. Nobody would seriously ask whether Master Splinter’s ninjutsu in TMNT is historically accurate, for instance.

So basically, as my students put it, you’re going to ruin ninja for us? I’d say that my aim is not so much to ruin ninja as it is to pay this complex, fascinating, and sometimes infuriating figure the respect it deserves. I can do that, above all, by studying it seriously, by giving people a more rigorous, evidence-based account of what the whole ninja thing is all about. You don’t have to believe that historical pirates were exactly as depicted in Pirates of the Caribbean to enjoy the movie series, after all, so I don’t think that enjoyment and celebration of the ninja needs to depend on their being exactly as advertised by ninja ‘historians.’

What you can expect over the next few weeks and months will mostly fall into either the historical or the literary, as mentioned above:

· Summaries and reviews of existing English-language books on ninja history (spoiler alert: most of these reviews are going to be negative).

· Partial translations and summaries of recent Japanese-language publications on the topic of the ninja – there is good stuff out there, but the language barrier makes it inaccessible to general audiences.

· The state of the field of ninja studies – what the endemic problems are, how they lead to bad history, and how we can plot a path to doing better.

· Discussion of the ninja’s place in academia – right now it basically doesn’t have one.

· Previews of my own ninja research as it develops and is published.

· Reviews of ninja movies from Japan and elsewhere.

· Serialized translations of Japanese fiction, starting with the 1914 Sarutobi Sasuke series from Tachikawa Bunko.

It’s generally considered good practice to include the original Japanese for terms that are translated or romanized, but I know not everyone can read Japanese or wants to, so I’ll put the Japanese in the footnotes so you can ignore it if it’s not useful. Here, it’s Naruto ナルト and Ninja Hattori-kun 忍者ハットリくん.

Also, concerning citations: we’re going to be returning to many of the same books over and over again, so what I’ll do is provide a full citation for a book the first time I mention it, then shorten the citation from then on. You should also check out the Reading List page, which will always have full citations and which will be expanded as we progress.

The first four would be Ninja: The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult (Poole, UK: Firebird Books, 1991), Ninja: AD 1460-1650 (Oxford, UK: Osprey Books, 2003), Warriors of Medieval Japan (Oxford, UK: Osprey Books, 2007), and Real Ninja: Over 20 True Stories of Japan’s Secret Assassins (New York: Enchanted Lion Books, 2008).

You should know, though, that since 2015 Turnbull has publicly walked back his stance on ninja and disavowed some of his earlier publications; see his article "The Ninja: An Invented Tradition?" Journal of Global Initiatives: Policy, Pedagogy, Perspective: Vol. 9 No. 1 (2015) and his Ninja: Unmasking the Myth (Frontline Books, 2017). I’ll discuss Turnbull’s change of heart in a later post.

Kacem Zoughari, The Ninja: Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan (Tuttle, 2010)

Shinobi 忍び

Hi Peter,

There are a few pieces in English prior to 1960. One is Gingetsu's 1918 article, which is available online and which I linked to in the next piece on the site, "The Ninja As History."

After that, I don't think there was anything in English until 1957, a one-page article in the English-language Japan Magazine entitled "Ninja, the Japanese Supermen: Could Perform Unbelievable Physical Feats; Grueling Training Utilized in Espionage."

Then, in 1961, you have an article in the men's magazine Argosy entitled "The Art of Invisibility," which is a profile of Hatsumi Masaaki's ninjutsu and how it's a continuation of the shadowy assassins of the medieval period. Argosy was a pretty trashy publication, though, and the overall tone of the article is not exactly reverential toward Hatsumi or particularly serious about ninjutsu.

This is followed shortly after in September 1961 by a piece by Donn Draeger in the English-language journal This is Japan, entitled "Invisible Men with Secret Weapons." This is actually an article about martial arts training in general, really, but it opens with a page or two about the ninja. I think Ian Fleming read this during his trip to Japan in 1962, before You Only Live Twice, and it may have been his first point of contact. We know that Fleming worked with the editor of This is Japan, who later shows up in You Only Live Twice as 'Tiger Tanaka.'

We might also include Jay Gluck's 1962 book Zen Combat, which has a short chapter devoted to ninja and ninjutsu. Gluck mentions the Argosy article, but to be honest does not seem to take Hatsumi and his ninja weapons very seriously.

So I guess 1960 is kind of my way of providing a rough marker that splits the difference between 1957 and 1961-2 or so, if that makes sense.

Greetings, as you know, I have been doing my own research along these very same lines and publishing them on my own substack ( Mostly Asian History / https://peterhuston.substack.com/ ) -although I fully admit that as a scholar in the field of Japanese studies you do have an edge over me.

But I have a question. You wrote: "almost everything written on the topic of the ninja in English since 1960 is garbage." Why 1960? Was there anything significant written on ninja in English before 1960? My understanding is that the first reall, significant writing featuring ninja in English was Ian Fleming's James Bond novel, "You Only Live Twice," and that came out in 1964. (In fact, I was planning to write on this at some point.) -- Looking forward to your response. And best of luck with this and looking forward to reading more.