The Root of the Problem: Itō Gingetsu

The OG 'ninja' researcher, who left the field some problems it's yet to get over

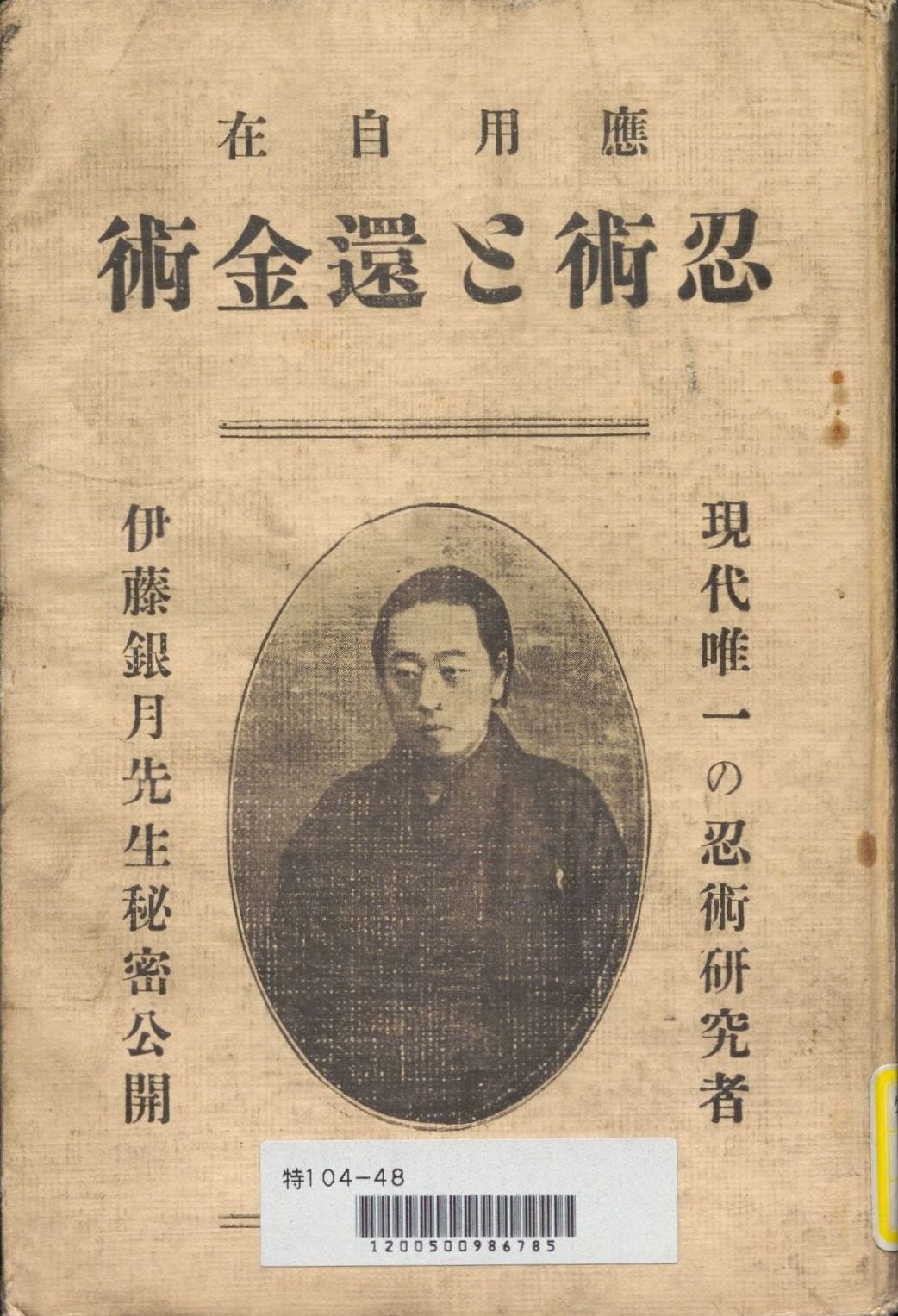

The writer and journalist Itō Gingetsu (1871-1944) was probably the first person to argue for what we now think of as the modern ‘ninja.’1 Born in 1871 in Akita Prefecture, in the far north-west of Japan’s main island, Gingetsu grew up there before dropping out of middle school and moving to Tokyo, where he kicked around for a while before getting a job at the Yorozu chōhō newspaper in 1898.2 The Yorozu was, by contemporary standards, a bit of a tabloid, with a penchant for muckraking stories about Japan’s rich and powerful, and as you might expect it had better circulation figures than many of the more ‘serious’ Japanese newspapers of the time.

Gingetsu himself would finish as a very prolific writer on all sorts of topics, with the National Diet Library listing him as author or editor on over a hundred books published between 1898 and 1944. Though now reasonably well-known to ‘ninja’ enthusiasts, he was hardly a one-trick pony; his published interests include poetry, alchemy, the life of Japan’s first modern Prime Minister Itō Hirobumi (no relation, as far as I’m aware), pirates, and a whole bunch of other stuff, as you can see at the above NDL link if you read Japanese.3

As far as we’re concerned, though, it’s his stuff on ‘ninja’ that’s most important. In what follows, I want to acknowledge the role Gingetsu played in shaping subsequent discourse on the ‘ninja’ in Japan and elsewhere. That role is, as I see it, both positive - he was probably the first writer to outline the contours of the topic - and negative, since in defining the study of the ‘ninja’ he left it some massive methodological problems that have hampered the field’s ability to do serious history ever since.

Gingetsu Smells a Rat

Gingetsu’s first work on the topic of the ‘ninja,’ entitled Shadow Magic and Illusion Magic (Ninjutsu to yōjutsu) was published in book form in 1909.4 It was, I believe, a collected version of a series of columns Gingetsu had previously published in the Asahi shinbun newspaper, another major daily of the time.5

Shadow Magic and Illusion Magic is in many ways a frustrating text to work with, because Gingetsu is a rambling and sometimes borderline incoherent writer. This seems to have been a widely-known thing about him, leading to the term “Gingetsu style” (Gingetsu-shiki) being coined to describe his free-ranging and often whimsical style of writing.6 It can be difficult, therefore, to figure out precisely what Gingetsu thinks ninjutsu is, but best I can figure, he sees it as a system of semi-mystical, ascetic physical training. Among other things, Gingetsu believes that one must go through fasting and sleep deprivation, learn special techniques for breathing, and learn other special techniques of walking and bodily movement. If these techniques are mastered, Gingetsu claims, one can then achieve a number of physical feats that, to an uninitiated observer, appear to be literally magical.

What’s most interesting to me is where Gingetsu is getting his examples of apparent feats of magic, because some of these are going to sound very familiar:

Nikki Danjō turned himself into a rat and stole a scroll. Jiraiya used toad magic and was able to do whatever he wanted. […] Now, in the end, all of these are just the products of the novelistic imagination - but no matter how much they may have come from the imagination, one cannot take complete and utter fiction and fashion it into what appears to be truth. According to my studies, one who has trained sufficiently in ninjutsu will, as a result, be able to legitimately achieve these acts of illusion magic (yōjutsu).7

Gingetsu’s points are that the magic of Nikki Danjō and Jiraiya must have some kind of real-world basis to it, and that with sufficient training the effects of that magic can be reproduced in the real world.

As I said, it can be difficult to figure out what Gingetsu is getting at sometimes, so to make sure that that is indeed what he’s saying, let’s look at his next chapter, helpfully entitled “The Technique of Becoming a Rat.”8 This starts with a brief reprise of the famous “under the floorboards” scene from the 1777 play Precious Incense and Autumn Flowers of Sendai, which we’ve covered in the previous few posts and which I won’t re-summarize here. Then we get to Gingetsu’s main argument about this well-known scene, in which the evil wizard Nikki Danjō has transformed himself into a rat:

In plays and prose fiction, it must necessarily be held that the character has indeed transformed into a rat so as to keep things interesting, and so the work will maintain that that is what happened. The truth of the matter is that this is merely a mode of description, albeit a mode that makes one sigh in admiration. The work in question says that what happened is that a human turned into a rat, so when the story comes to be depicted in pictorial art or given concrete shape in some other way, or expressed in written words, the actual accounts that are passed on focus on the bit about there being a rat the size of a human.9

We might summarize Gingetsu’s point here by saying that he believes that the story of Nikki Danjō is on some level a reflection of real events, albeit heavily embellished in the interests of literary interest and creativity. Gingetsu has fairly clear ideas as to what those underlying real events must have been, since he goes on to argue that someone who has mastered the physical techniques he is talking about will become able to move extremely quickly and across sheer surfaces with ease. Therefore, Gingetsu suggests, those who behold such a man would think that this extremely agile figure was a rat:

That person will be so fast that the eye cannot register him, and it is perfectly reasonable that [an observer] would describe what they saw as a rat. Not only that, but the person might well appear to be a rat in the eyes of one who caught but a glimpse of him.

“What was that? A rat, maybe?” they would start wondering, and then in the end, arrive at the conjecture “Must have been a rat, didn’t seem like it could be anything else,” which conjecture then becomes “A rat, probably,” which must then be boiled down to “Definitely a rat, no question.”10

Making the Magic Real

I hope that Gingetsu’s argument is clear, or at least as clear as it can be given its author’s rather rambling prose style. Gingetsu believes, in essence, that Nikki Danjō’s magical powers in Precious Incense are in fact based on some highly embellished real event long ago. The nature of this real event, as he explains, was probably that some individual skilled in ninjutsu techniques moved so fast in stealing the scroll that the people who saw him believed that they had in fact seen a rat. This, so the argument goes, must be the foundation of the story.

The thing about Gingetsu’s argument is that it is - please excuse the academic jargon here - wrong.

I mean, it’s true that fiction writers often base their work on real-world things that they see around them, after all. But when Gingetsu suggests that fiction cannot be fashioned out of things with no basis in reality, as he does above, he is failing on a very basic level to understand what fiction is. In trying to explain Nikki Danjō’s scroll-stealing, shape-shifting antics by recourse to what someone might have done in the real world, Gingetsu is attempting to explain something that does not require an explanation. The only explanation you need in order to account for Nikki Danjō’s magical powers is that the play Precious Incense is a work of fiction. That’s it. End of discussion. We don’t need to account for what might have “really” happened because there isn’t necessarily any “really” here.

There is a second sense in which Gingetsu is within the ballpark of a point, though it’s more abstract than the one he is attempting to make. It is true that works of fiction that become popular often do so because they speak to some real-world issue or experience in their readers. The Harry Potter novels, for instance, clearly resonated with a broad swathe of teenagers who found in Hogwarts Academy something they perceived to be lacking in their own schooling. More broadly, the structure and workings of Hogwarts - which is after all a private, selective school - seem like they’re consciously or unconsciously reflecting the strong influence of social class in the British school system, and the divisions between those who get to go to fancy, expensive schools like Eton, Harrow and so on, and those who don’t. Consider the conflict between the “pureblood” Draco Malfoy and the Muggle-born but extremely bright Hermione Granger, for instance, and you’ll see what I’m talking about.

But just so we’re clear, that’s not what Gingetsu is arguing. To stay with the Harry Potter framing, what Gingetsu is suggesting is the equivalent of arguing that the Avada Kedavra death spell in Harry Potter must be based on something in real life, and so its effects must be replicable in the real world. For those who may not be aware, the Avada Kedavra spell, as depicted in the novels and (inconsistently) the films, causes a flash of green light, at which its victim drops down dead:

So OK, what this must really have been is that the wizard conceals a small flashlight with a green filter on it up their sleeve, turns on the green flashlight just for a moment, and then shoots the victim with a small pistol in their other hand, and the victim drops down dead, and everyone around them thinks that it’s a magic spell.

You see how ludicrous Gingetsu’s argument is when applied this way to a more familiar work of fiction. The Avada Kedavra spell does not require any explanation other than “it’s a work of fiction,” and neither do Nikki Danjō’s magical powers in Precious Incense.

I hope you will have noticed, also, that Gingetsu’s investigation into ninjutsu here takes as its starting point works of fiction. As he’s discussing ninjutsu, the examples of things that practitioners can do are taken not just from Precious Incense but from the characters Jiraiya and Tsunade in the early 19th century Jiraiya fantasy novels and plays, the characters in Takizawa Bakin’s hugely popular prose work Eight Dogs Chronicles, and a few other works of Edo-era fiction and semi-fiction.11 In essence, what Gingetsu did was to find accounts of magical powers in Edo-period fiction, assume that they must be true in some sense, and then go seeking the historical evidence that he believed supported his case. He did kind of find it, or thought he did, anyway, as his next major work, The Ultimate Meaning of Ninjutsu (1917) shows that he’d found a copy of the ‘ninja manual’ Shōninki, but we’ll leave that discussion for another day.12

So in essence, Gingetsu started with works of fiction and then tried to figure out a way to make them fit into the real world. And this matters, because whether they knew it or not the majority of ‘ninja’ historians who came after him, Western and Japanese, have often been doing the same thing.

Since we’re almost out of space for today, in the next post I’d like to show how endemic this “must have been” idea would become to the practice and methods of ‘ninja’ history. The wrong-headed assumption that fiction must always be true in some sense is, as we’ll see, not just one quirky oddball’s approach; it would remain a consistent element in ‘ninja’ history for a century after Gingetsu first introduced it.

Itō Gingetsu 伊藤銀月.

Akita Prefecture 秋田県; Yorozu chōhō 万朝報. ‘Yorozu chōhō’ literally means something like “all the news in Japan,” in case you’re curious.

Itō Hirobumi 伊藤博文 (1841-1909).

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu 忍術と妖術 (Ryōkōdō, 1909).

Eric Shahan, trans., Ninjutsu to yojutsu (Self-published, 2014), p. 11. Shahan’s translation is decent and a good general introduction to Gingetsu’s thinking. I’ve used my own translation above because on occasion I read Gingetsu slightly differently from Shahan, but I do recommend Shahan’s book to anyone interested in the topic, especially as Gingetsu’s earlier work is not always easy to access in the Japanese original.

Gingetsu-shiki 銀月式; per “Itō Gingetsu,” entry in Nihon kindai bungaku daijiten (online version, accessed via Japan Knowledge 5/24/25)

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu (1909), p. 74. Japanese: 仁木弾正が鼠に化けて巻物を盗む、児雷也が蝦蟇の術を行つて好き放題の真似をする […] 畢竟小説的空想中の産物に過ぎないのであるが、いくら空想でも、全く根も葉も無いことを事実として組み立てられはしない、吾輩の研究によれば、忍術を十分に練習した結果をして、是等の妖術も正当に行ひ得るのである。(Here and below, I’ve changed kanji to post-1945 equivalents but retained original punctuation and kana usage).

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu (1909), p. 76. Japanese: Nezumi to naru jutsu 鼠となる術.

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu (1909), pp. 78-79. Japanese: 演劇や小説では、真誠に鼠になったことにしなければ面白くないから、それを事実としたのであらうが、其実これは形容詞に過ぎないのである、讃嘆を加へた形容詞なのである、人間が鼠に化けるのだからと云つて、絵に描くにも、形に表すにも、文字で意味するにも、人間程の大きさの鼠とする所に、実際の消息が伝へられているのである。

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu (1909), p. 80. Japanese: 其速きこと目にも止まらぬ程であつたら、これを形容して鼠と云ふも差支無いのみならず、実際瞥と見た者の目に鼠と映ずるであろう、「何だらう、鼠かも知れない」と云ふ怪訝の果は、「どうも鼠より外の物とは思はれない」と云ふ推測に移り、其推測も「鼠だらう」に進んで「鼠にちがひない」と迄に煎じ詰められなければならぬ。

Takizawa Bakin 滝沢馬琴 (1767-1848). Eight Dogs was absolutely huge during the 19th century, one of the most widely-read fictional works of the entire Edo period. It’s also massive, serialized over multiple decades, but it’s being translated into English by Glynne Walley at the U of Oregon, so if you’re interested (and have a couple of spare years to set aside), check it out.

Kishimoto : make ninjutsu magic again

First you ruin ninjas, now you spoil wizards too? 😩 Next you’ll tell us time travel isn’t real either (or maybe you already have).