All The World's A Stage, and All the Ninja Merely Players

Can you use fiction to write history, and if so, how?

Crack open almost any English-language ‘ninja’ book of the last fifty years and you’re likely to read something like this, from Stephen K. Hayes:

The historical lore of Japan’s ninja night warriors is full of tales centering around seemingly fantastic abilities that reach far beyond the capabilities of normal mortals. Of course, the exaggerated tales are based on roots of reality, which were then nurtured into the flowering of myth and misunderstanding. Skills of becoming invisible, the power to transform shape, and methods of flying through space and time are perhaps the most common ninja legends.1

Or this, from Stephen Turnbull:

Ninja certainly existed, but so much myth and exaggeration has grown up around the undoubted historical core of the subject…Any references to ninja that could fly will be identified as the myths they are.2

The reader is being led to understand that there exist many stories of ‘ninja’ with magical powers in Japan, and that these stories are in some sense based on historical reality. More specifically, the magical powers used by ‘ninja’ are in truth misunderstood reflections of amazing yet real-world infiltration skills. As Donn Draeger puts it:

As reports of persons who had seen ninja perform skillful feats accumulated over the years, exaggerations of facts made the ninja out to be a superhuman.3

The implications of this claim, if true, would be that ‘ninja’ activity was a constant in Japan over several hundred years. Lots of people noticed it, but the superstitious Japanese populace did not understand what they were really seeing, and so ‘ninja’ skills came to be misinterpreted as magical powers.

I think this argument is nonsense. I dispute the notion that ‘ninja’ as most of us understand them are in fact depicted in what Hayes refers to as “historical lore,” but I’ll save that topic for the next post. Today I want to focus on a different rebuttal to Hayes et al, which is that it’s intellectually incoherent to argue that depictions of magic in Japanese “lore” are historical evidence for the ‘ninja.’

Let me explain.

“The Problem Is He Doesn’t Realize It’s Made Up”

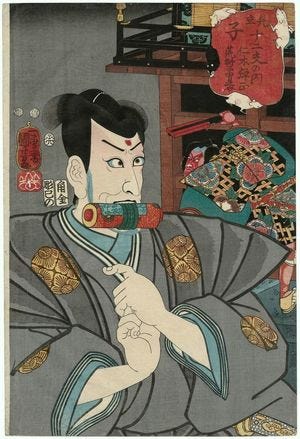

The first thing to understand is that when Hayes and Turnbull talk vaguely about “lore,” “tales,” “myth,” and so on, what they are referring to is Japanese literary fiction, mostly plays and prose works produced between about 1700 and 1965 or so. Hayes’ passage about “exaggerated tales […] based on roots of reality” in his 1985 book appears directly opposite the print of Nikki Danjō we saw in the previous post, in fact, and “becoming invisible” and “transform[ing] shape” is exactly what Nikki Danjō does in Precious Incense. So the clear implication is that Hayes believes that this 1777 play proves something concrete about the historical ‘ninja.’

Once we clarify that “historical lore” in this context means works of literary fiction, the incoherence of Hayes et al’s argument become obvious. To recognize that plays such as Precious Incense are fiction is to say that - and I’m sorry for making such a clunkingly obvious point here - parts of the play are made up. That is, quite literally, what the word ‘fiction’ means.

The approach Hayes et al are taking here confirms a point I’ve made previously, which is that on a fairly basic level the field of ‘ninja’ history seems to be confused by the very concept of fiction. Over and over again, the most prominent ‘ninja’ writers seem unprepared to deal with the fact that people can make things up. It reminds me of the below bit in the 80s British comedy Blackadder the Third, where the dimwitted Prince Regent (played by Hugh Laurie, later of House fame) gets really into the theater but fails to grasp that what he’s seeing on the stage isn’t real, that Julius Caesar is not literally being murdered before his eyes (“Look behind you, Mr. Caesar!”):

Double, Double Toil and Trouble

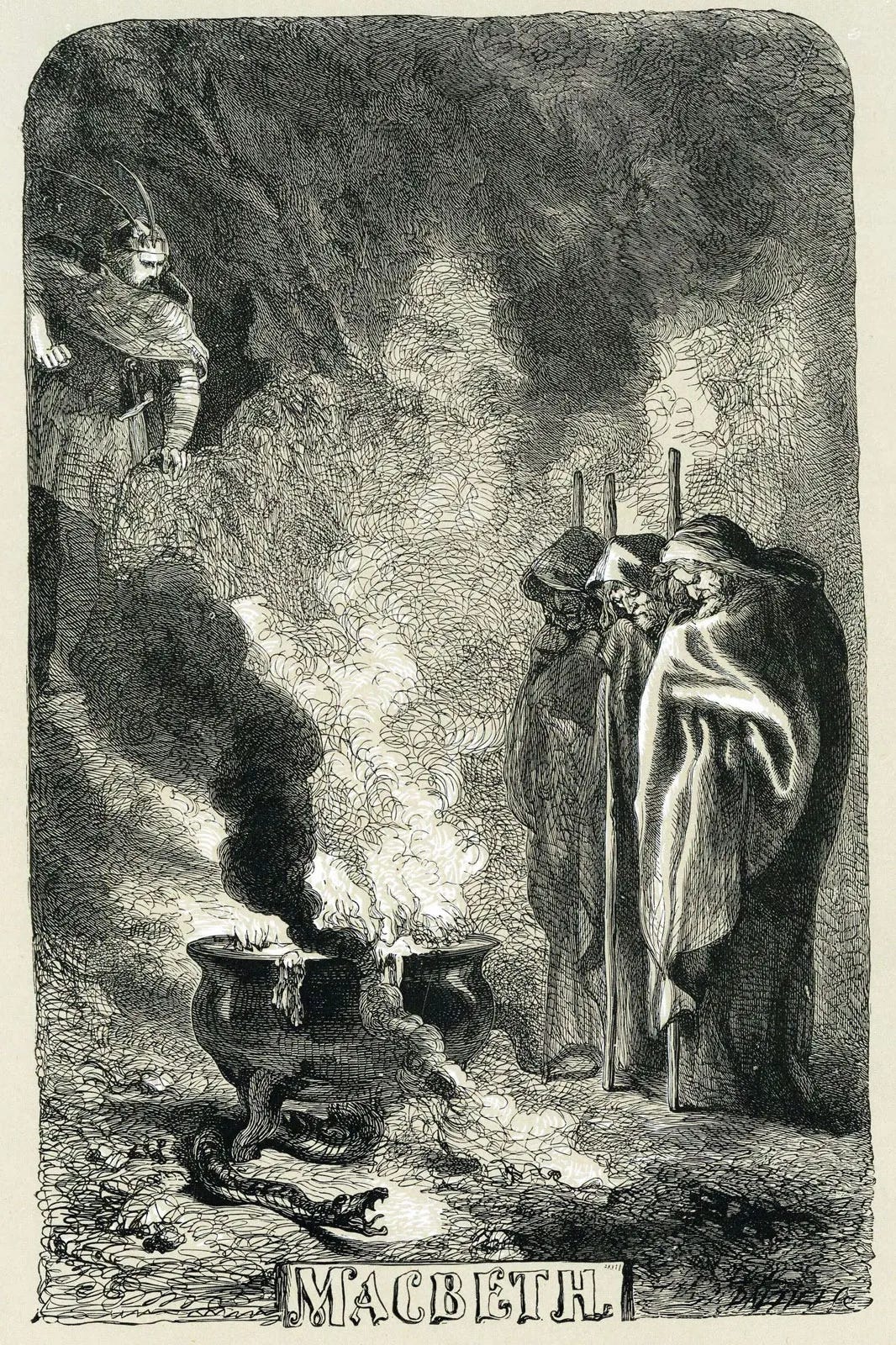

Now, in partial defense of Hayes et al, you can in fact draw certain historical conclusions from plays or other works of fiction. Most literary scholars agree, for instance, that fictional works reflect certain aspects of the historical societies from which they emerge. To pick just one example, when I did Shakespeare’s Macbeth in middle school in the mid-1990s, we noted that the play’s presentation of malevolent witches and dark magic reflects a real-world witch craze in England and Scotland around the time the play was written and performed.

So perhaps we could try applying Hayes et al’s methodology to the witches in Macbeth, since that play is much more familiar to English-speaking readers than Precious Incense. Looking at Macbeth’s witches, then, there’s a range of possible historical conclusions we could draw about England in Shakespeare’s day from their presence, starting with the most unlikely:

Witches with magical powers existed in Jacobean England exactly as depicted in Macbeth.

Few modern literary critics would take that claim seriously, though. This leads to a slightly more refined version:

Women roughly analogous to witches existed, but they didn’t literally have magical powers; rather, they had ways of exerting seemingly uncanny influence through entirely mundane means.

As you’ll realize, this is essentially a transposition of the ‘ninja’ argument.

Now, both #1 and #2 make a common assumption, which is that the witches in Macbeth must be based on something that really existed. But again, and I apologize for repeating myself, Macbeth is fiction. What we see in the play doesn’t necessarily have to have a real-world correlate; Banquo’s ghost does not imply that ghosts really exist. This leads us to other possibilities outside of what Hayes et al have considered:

Witches did not exist in either a literal or metaphorical sense, but people in Jacobean England thought they did.

That is to say Macbeth could well reflect a widespread belief in witches in early 17th century England, rather than their actual existence. And also:

The whole ‘witch’ trope is complete fiction, and nobody really thought witches existed. They’re there purely for fright value, kind of like (say) the zombies in in The Walking Dead or Freddie Krueger from Nightmare on Elm Street.

The point I’m making is that although you can in theory draw historical conclusions from literary works, doing so in convincing fashion is not as easy as Hayes et al’s simplistic “it’s in the play, so it must be real in some sense.” The reality, as we’ve just laid out with Macbeth, is that Nikki Danjō’s magical powers don’t necessarily need to have any kind of real-world correlate at all. That, once again, is what fiction means.

The Words “Based On” Don’t Get You Out of Doing the Work

I noted in the previous post that like many kabuki plays Precious Incense is based on real events, and the character of Nikki Danjō is believed to be inspired by a real person named Harada Munesuke, who lived from 1619 to 1671. A more refined version of Hayes et al’s argument might therefore be that yes, in and of himself the fictional character of Nikki Danjō can’t tell us anything about the historical ‘ninja,’ because he’s a fictional character. But maybe we don’t have to discard Precious Incense completely; since Nikki Danjō is based on a real person, perhaps his real-world analogue Harada Munesuke was suspected of having magical powers, or actually was a ‘ninja’ himself? Maybe that’s how the admittedly fictional play could point us towards the historical fact of the ‘ninja.’

This is a defensible position, but thinking about it a bit reveals that it’s actually an argument for the ultimate irrelevance of Precious Incense itself. If we want to argue that the real Harada Munesuke was renowned for having magical powers, we can’t do it through the play alone; we would have to support that claim by searching for other, non-fictional sources that mention Harada Munesuke being a wizard. And once we acknowledge the fact that external sources are needed to support the argument, we have to acknowledge that strictly speaking Precious Incense itself is irrelevant to the historical case.

Let me put it another way. I’ve used Orson Welles’ Citizen Kane a few times now as an example of the slipperiness of the “based on” thing, because we know that the film’s main character Charles Foster Kane is based on the real-life newspaper magnate William Randolph Hearst. Some of the lines Kane delivers in the movie are apparently very close to things Hearst is known to have said in real life. But you cannot know which parts of Citizen Kane are true to life and which are made up from the film alone; to determine that, you have to find external historical documentation of the things Hearst said.

So whether you want to use Charles Foster Kane to talk about the historical Hearst or Nikki Danjō to talk about the historical ‘ninja,’ you have to do the work. To successfully do what Hayes et al are trying to do, you would need to go and read the primary sources about Harada Munesuke and find the evidence that suggests Harada was known for having magical powers. What you can’t do is what Hayes et al actually do, which is to present pictures of a fictional character, wave vaguely at “tales,” “lore,” “myth,” “legends,” or whatever, and casually assume that fictional works alone provide convincing proof of historical claims.

Some readers may well wonder why ‘ninja’ historians would turn to fictional works as evidence in the first place. If the historical evidence for ‘ninja’ is as convincing as, say, Turnbull claims (“the undoubted historical core”), then why bother resorting to fiction at all? The obvious conclusion would be that fiction is pretty close to all they’ve got; when you have a book to write but the historical evidence isn’t really there, you gotta go somewhere else.

Another explanation is simply incompetence, that reliable constant in the field of ‘ninja’ studies. Andrew Adams, Donn Draeger, and Stephen Turnbull all have track records of failing to realize that some of the ‘ninja’ they were talking about were fictional, so it’s entirely possible that the same thing happened here and at least some of our guys didn’t grasp that Nikki Danjō never existed.

The take-home point, I suppose, would be that two whole generations of ‘ninja’ historians haven’t always been doing history, as they believed themselves to be; they have instead been doing a form of literary criticism, and doing it extremely badly.

To move forward with our discussion of Nikki Danjō, I’d like to turn to thinking about the issue I raised at the beginning of the post, which is whether it’s justified to think about characters like the evil sorcerer as ‘ninja’ in the first place. So that’s where we’ll go next - is Nikki Danjō even a ‘ninja’ in the normal sense, anyway?

Stephen K. Hayes, The Mystic Arts of the Ninja: Hypnotism, Invisibility, and Weaponry (Contemporary Books, 1985), p. 133.

Stephen Turnbull, Ninja: AD 1460-1650 (Osprey, 2003), p. 4.

Donn F. Draeger, Ninjutsu (1971; my ed, 1989), p. 96.

I think there should be in-depth research related to the ninjutsu tsukai boom (1920) and its connection to actual shinobi activity (sengoku period), is this really a historical connection or is it just a matter of language, I mean nin from the beginning has had a double meaning, it can be magic or secret

*sorry for my bad english

So, with the whole 'ninja lore' you've been exploring (for us), I learned this new category of a researcher – *pop-historian* (until now I only knew "historian", and "historical researcher", which I see as A. Cummins' attempt to get away with doing history without primary sources). Turnbull would perhaps be this *pop-historian*, I guess Lockley would be as well (and we have some of those here too).

I hope you'll get to the Japanese *pop-historians* soon. Japanese academia is often quite different from the West, and I wonder how much true this is for the history (vs. *pop-history*). My guess is that while Yamada Yūji would fall under "historian", Itō Gingetsu or Okuse Heishichirō would be the *pop-historians*... I'm brainstorming here, so I hope you'd elaborate... Thanks.