As we’ve seen in our previous few posts, there are plenty of people wearing black head coverings in Edo-era prints, but the figures depicted are almost never ‘ninja’ in the modern sense when you check the stories behind the prints. The available evidence also suggests that Edo-era Japanese viewers did not read these figures as ‘ninja’ or even necessarily as shinobi; rather, the black hood was a means of signalling to the reader that the figure was doing something clandestine. Such coverings could be - and were - worn by almost anyone in lots of different contexts, rather like the Lone Ranger’s eye-mask.

So at least as late as the first years of the 20th century, a guy with his face wrapped in black isn’t interpreted as ‘ninja,’ but by the time we get to the 1960s, he almost always is. This should cause a good scholar to ask: OK, when did the idea that ‘ninja’ wore black masks first get started in Japan? In more academic terms, when did the black hood acquire this specific cultural meaning? Can we specify the precise point at which it emerged?

I think we can, or at least we can get pretty damn close.

Itō Gingetsu: The First ‘Ninja’ Writer…

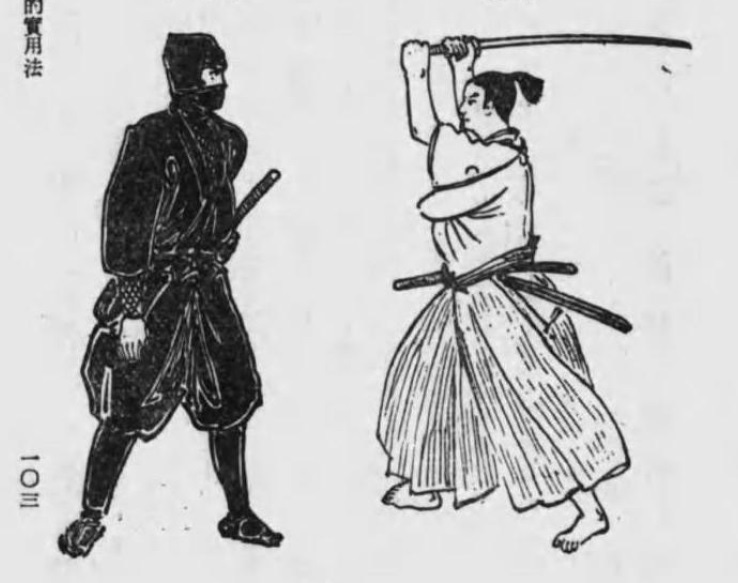

As far as I can tell, the earliest occasion where we have a depiction of the classic ‘ninja’ outfit specifically linked to the shinobi is in 1909, in Itō Gingetsu’s book Ninjutsu to yōjutsu (Shadow Magic and Illusions).1 It contains this illustration, which I reproduce here from Eric Shahan’s 2014 translation of the text:

The caption on the left-hand side reads “the six techniques of the shinobi” (shinobi roppō), and the illustration depicts a specific way of walking sideways that Gingetsu describes as a “mysterious technique that anyone can do” (dare demo dekiru fushigi no jutsu).2 So this would seem to be intended as a shinobi in the historical sense, and in fact Gingetsu does suggest in his 1909 work that a ninjutsu-sha - which, in this specific case, he defines as someone who is sneaking into somewhere - should not wear black, because it stands out too much.

This is probably the origin of the whole trope whereby the apparently knowledgeable ‘ninja’ expert tells us that actually ninja didn’t really wear black, one you will certainly have seen if you have had the misfortune to stumble across any online debate about what ‘ninja’ did or didn’t do. It’s interesting to note that the disavowal of wearing black appears to have been there right at the inception of the modern ‘ninja,’ rather than being a misconception that needed to be corrected later.

Rather than black, Gingetsu suggests, an infiltrator should wear black blended with red dye.3 Note that at this stage, at least, Gingetsu doesn’t specifically say that ninjutsusha regularly covered their faces; I suspect that the illustration in 1909 may well be drawing more on Edo-era visual conventions for concealment than it is intended as an actual historical claim.

…and Also Frankly Kind of an Oddball

It’s worth taking a few moments to say a bit about Itō Gingetsu himself, because we’ve mentioned him in these pages before and probably will again. Born in 1871 in Akita Prefecture in the far north-west of Japan, Gingetsu was a journalist and writer, and a very prolific one at that - the National Diet Library catalogue lists no fewer than 161 books or articles for which he’s credited as the main author or editor, starting in 1901 and going on into the early 1940s. He was, as we’ve seen, probably the first person to introduce something resembling the modern ‘ninja’ to English-speaking audiences way back in 1918, but his range of writing was by no means limited to ‘ninja,’ as he also published books on all kinds of topics such as alchemy, poetry, and even a history of pirates in Japan. (Hey, maybe that’s where the ‘pirates vs. ninjas’ thing got started?)

Having read a certain amount of Gingetsu’s work, I have to confess I am unsure how seriously to take him. He appears to have a semi-humorous, kind of rambling style in the original Japanese, and it’s never entirely clear to me whether he’s seriously advancing a set of historical arguments or just having fun with the reader. From my reading of his earlier work, he seems - like many Japanese people born around the same time - to have been very ambivalent about Japan’s modernization project, which was gathering steam as he was growing up in the early Meiji period. In particular, I get the sense that Gingetsu’s interest in ninjutsu grew out of a wish to try to rescue something real from all of the fantastical tales of magic and uncanny powers from the Edo period. Reading between the lines of his writings, I think he didn’t want to accept the way in which modernity and scientific rationalism dismissed these stories as simply fantasy, and wanted, in his own way, to challenge modernity by showing that there was an element of truth to these stories of magic and mystery.

Let’s get back to the ‘black face covering’ thing, though. Turnbull’s 2017 Unmasking the Myth, which is far better than his earlier books, suggests that the classic ‘ninja’ outfit wouldn’t make its appearance until 1937, when Gingetsu published a book entitled Gendaijin no ninjutsu (Ninjutsu for People Today).4 Turnbull includes the below image in the color plates to Unmasking the Myth, and describes it as:

probably the first drawing of a ninja figure in a realistic fashion with the overt intent of portraying a specialist rather than just any warrior or assassin who wished to conceal his identity.5

Having looked through Gingetsu’s Gendaijin no ninjutsu, it’s worth noting that this isn’t the only depiction of a ‘classic ninja’ in the book. In fact, by now, in 1937, the familiar ‘eyes-only’ mask has become Gingetsu’s favored motif, because he uses it consistently across most of his illustrations. As you may have noticed, the Edo-era prints we’ve seen to date show some variation in the head coverings of the guys depicted; some have only their eyes visible, some are wearing loose hoods, and others have their face visible but have wrapped a scarf around their heads vertically (I’ll call these three variations ‘eyes-only,’ ‘hood,’ and ‘bonnet’ respectively). But by 1937, Gingetsu seems to have settled on ‘eyes-only’ as a consistent visual motif for his ninjutsusha. You can see this for yourself courtesy of the amazing NDL Digital Library, where you’ll see that almost every figure in the book is wearing the ‘eyes-only’ variant covering.

So I think Turnbull is right that Gingetsu was the first to associate the black-clad figure with the specialist infiltrator, though I think he may be putting the date of its first occurrence too late in 1937, because Gingetsu’s earlier The Ultimate Meaning of Ninjutsu (Ninjutsu no gokui, 1917) contains the image we saw at the top of the page, reproduced in smaller size here:6

This guy seems to be wearing the ‘bonnet’-type head covering, which looks to consist of a scarf or cloth wrapped around the head vertically. It’s definitely associated with a specialist infiltrator in this context here, since that’s exactly what Gingetsu is talking about in the accompanying text. In fact, he’s discussing how ninjutsusha - as he calls them - carried certain specific tools on their missions, including a three-foot length of special cloth that could be used for various purposes, including being worn as a belt, used as a bandage, or - yes - wrapped around the head when sneaking in somewhere.7 (I suppose you could counter that the 1917 illustration isn’t the classic ‘eyes-only’ head covering, but for me it’s close enough.)

Now, the next question is - where is Gingetsu getting all of his information from, about mixing red with black or with three-foot lengths of cloth? Well, happily Gingetsu tells us in his 1917 book - his source is a 17th-century text called the Shōninki, translatable as something like “The True Chronicle of the Shinobi.”8 And the Shōninki does indeed say that the shinobi toolkit included a three-foot cloth that could be wrapped around the head.

Hang on, Tuck. So you’re telling us that the ‘ninja hood’ thing actually does have a pre-modern textual basis? Didn’t you say a few posts back that there was no historical evidence that shinobi actually wore black?

Yes, I did, and I stand by that. In the next post, we’ll consider what Gingetsu has to say about this amazing three-foot cloth, and also consider exactly what texts like the Shōninki can - and, more importantly, can’t - tell us about medieval Japanese history.

Ninjutsu to yōjutsu 忍術と妖術, originally published in 1909 by Ryōkōdō 梁江堂. It’s available in English translation by Eric Shahan as Ninjutsu to yōjutsu (2014).

You may wonder why I have translated ‘ninjutsu’ as “shadow magic” here rather than as simply ‘ninjutsu.’ The reason is that for much of Japanese history the term ninjutsu was often understood as referring to magical powers rather than the martial art taught by Hatsumi Masaaki and his successors. In fact, when Hatsumi began teaching his ‘ninjutsu’ in the 1960s, he had to specifically explain to audiences that his ‘ninjutsu’ was “scientific” and not a form of magic involving transforming into giant toads or anything. See, for instance, Hatsumi’s 1964 children’s book, Ninja and Ninja Skills Illustrated, p. 10. This point about ‘ninjutsu’ also meaning ‘magic’ is made clearly and concisely by Turnbull in his 2017 Unmasking the Myth, pp. 115-121.

Gingetsu, trans., Shahan, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu, p. 38. Japanese: shinobi no roppō しのびの六法; dare demo dekiru fushigi no jutsu 誰でも出来る不思議の術.

A little note on historical writing for the real geeks among us: If you can read Japanese, you may be wondering what’s up with the ‘shi’ of ‘shinobi,’ because it doesn’t look like the standard hiragana し. You’re absolutely correct - it’s an example of what’s called variant kana. Until 1900 or so, and sometimes even as late as 1945, there wasn’t necessarily only one kana for each sound like there is in today’s Japanese; sometimes other kana were used, though these fell out of common use after WW2 in favor of one for each sound. The ‘shi’ we see here is based on the kanji 志 but is still read as shi. There are, in some cases, four or five known variants for some kana. And you thought modern Japanese was hard…

Gingetsu, trans. Shahan, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu, p. 50. This section is also discussed in Turnbull’s Unmasking the Myth, pp. 124-125.

Gendaijin no ninjutsu 現代人の忍術 (Osaka: Kōjinsha, 1937). Turnbull discusses this figure on p. 127 of Unmasking the Myth.

Turnbull, Unmasking the Myth, page #11 of color plates between pp. 118-119. The same point is made in similar language on p. 127.

Itō Gingetsu, Ninjutsu no gokui 忍術の極意 (Bukyō sekaisha, 1917). This book has also been translated by Eric Shahan and is available as Ninjutsu no gokui: The Essense [sic] of Ninjutsu (2014). As with Shahan’s other translations, the actual translation is basically fine but the book needed better editing and proofreading, as shown by the typo in the title.

I’m not quite sure why Turnbull doesn’t mention Gingetsu’s 1917 illustration in Unmasking the Myth book. He definitely read Shahan’s translation, because it’s listed in his notes and bibliography. I think what may have happened is that Shahan’s translation contains mostly illustrations that are, as far as I can tell, Shahan’s own work, and so perhaps Turnbull thought that the ‘standing-on-a-sword’ picture was also drawn by Shahan. That’s an understandable assumption, but the image is actually in Gingetsu’s 1917 work, as you can see here.

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu no gokui, p. 69; Shahan p. 73.

Shōninki 正忍記, originally written c. 1681. It’s been translated by Minami Yoshie with editing from Anthony Cummins and is available in English as True Path of the Ninja: The Definitive Translation of the Shoninki (Tuttle, 2017). Gingetsu identifies this as his source in e.g. Ninjutsu no gokui, p. 68; see p. 72 of Shahan’s translation for the corresponding passage, though Shahan romanizes the book’s title as ‘Seininki.’