[Note: No post this coming Saturday 5th, because of the 4th of July celebrations in the US. We’ll resume on Tues 8th.]

It may be true, as I noted a post or two back, that no English-speaking academic has written anything very much about the kunoichi female ninja or about the Japanese novelist Yamada Fūtarō, whose popular novels of the 1960s did an awful lot to popularize the kunoichi. The ninja is nothing if not transnational, though, so a few months ago I was intrigued to find an article in a French journal from 2006, entitled simply “Les Ninjas Féminins” (‘The Female Ninja’), which does indeed discuss the kunoichi. It’s a short article, focused mostly on the purportedly historical kunoichi, but it does also acknowledge and explore the importance of the figure as media phenomenon. So, it seemed worth discussing the article here as a kind of coda to our discussion of the 1964 film Ninja Lady Magic.

Everything You Wanted to Know About French Surrealism

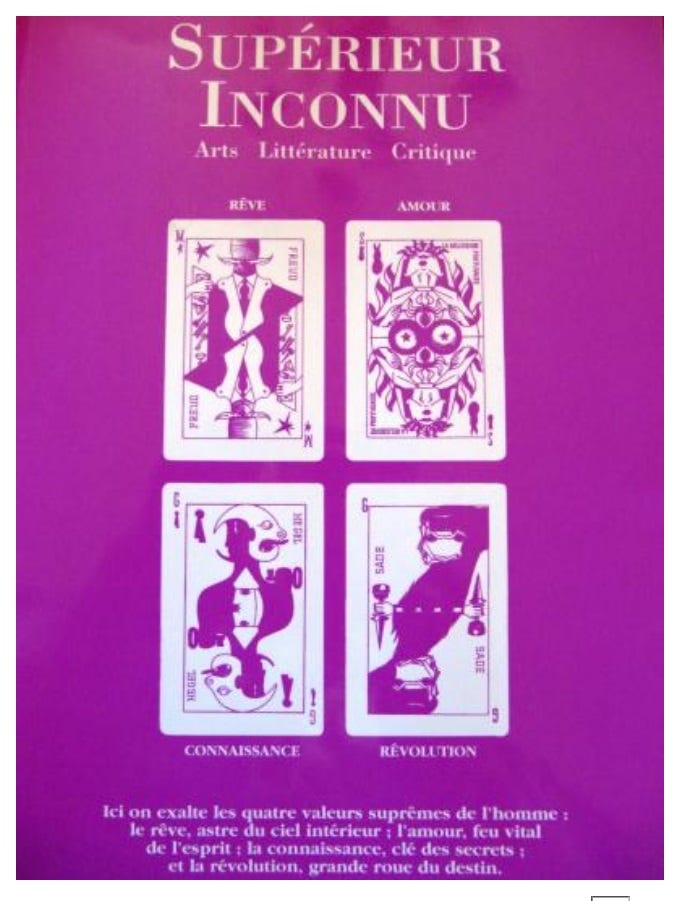

“Les Ninjas Féminins” is by a French scholar named Marc Kober, whose profile I think this is, and who works on Asia, the Middle East, and post-colonialism. The journal in which it appears is the enigmatically-titled Supérieur Inconnu, a phrase which means something like “Superior Unknown” and appears to have layers of double meanings I’m not really qualified to unpack.1 The title was suggested in 1947 by André Breton, basically the father of French Surrealism, but the journal itself didn’t actually start publishing until 1995, apparently because of the type of infighting for which movements such as Surrealism are notorious.2 During the period in which Kober’s article appeared, the journal’s articles were organized into four main sections (as you can see from the splash image above): Dreams, Love, Knowledge, and Revolution, all of these being major concerns of the Surrealist movement - to the extent that it’s coherent enough to have a set of main concerns. “Les Ninjas Féminins,” amusingly enough, appears in the “Love” (L’Amour) section.

I suppose it’s not hard to see why a Surrealist publication might be interested in the ‘ninja’ in general and in the kunoichi in particular. Most prosaically, the kunoichi figure as a whole (and specifically in Ninja Lady Magic) is so incredibly Freudian - sex, death, mother figures, poison vaginas, and so on - that it seems to fit quite well with Surrealism’s interest in the subconscious mind. As some readers may also be aware, well into the 1980s some forms of ninja discourse continued to have a sort of woo-woo semi-mystical aspect to them, insistence on “scientific” ninja arts notwithstanding. Hatsumi Masaaki, for instance, had a habit of talking about ninja and psychic powers, to the obvious embarrassment of some of his disciples. Stephen Hayes devoted a whole chapter to hypnotism in his 1985 The Mystic Arts of the Ninja: Hypnotism, Invisibility, and Weaponry, and then there’s…well, whatever the hell this is.

It’s a little disappointing, then, to find that Kober’s article doesn’t really attempt to do very much with the kunoichi mythos; instead, for the most part it’s an attempt at a straight historical study of the kunoichi. After likening them to the mythical Amazons and drawing a rather clumsy parallel between the supposed classic ‘ninja’ getup and the burqa, Kober then gives the reader a brief history of the ‘ninja’ activities that is so close to the standard Hatsumi/Draeger/Okuse/Hayes et al version that I won’t bother to re-hash it here. When we turn specifically to the kunoichi, it becomes obvious that the aforementioned individuals are almost certainly where Kober is getting his information from:

[I]t is mostly from the end of the fifteenth century that the kunoichi’s history begins, with the death of Mochizuki Moritoki in 1561. His widow, Chiyome Mochizuki, was put under the protection of the warlord Takeda Shingen, who tasked her with creating and leading a secret network of female ninjas.3

This is the widely-circulated story of Mochizuki Chiyome, supposedly the widow of a Takeda clan warrior, who set up a vast network of sexy female ninja disguised as shrine maidens (miko). We covered this a few months ago, and the TL:DR is that it’s bullshit. The Mochizuki Chiyome ‘ninja’ story first appears in 1971, and is almost entirely the invention of a pop historical writer named Inagaki Shisei. Chiyome herself may or may not have existed, but there’s no historical evidence to support the idea that she ran a massive network of female spies for Shingen.

Kober most likely got the Mochizuki Chiyome story from Stephen Hayes, who to the best of my knowledge was the first author to write about it in English in 1985. The next paragraph provides further evidence as to where Kober is getting his material:

The choice [for Chiyome’s recruits] was between becoming prey for all, being forced into prostitution and dying, or becoming a kunoichi. These women were indebted and devoted to their mistress, and readied for all kinds of missions of seduction. One may distinguish between two types of kunoichi; the shimma kunoichi (women of the ninja clan, part of the family) and karima kunoichi (who did not belong to a clan but whose services were hired […]4

The thing about shimma and karima is bullshit too, unfortunately, and it’s bullshit from a specific source. It’s from Okuse Heishichirō’s highly fanciful mid-1960s writings on ninja seduction techniques, which Kober may well be accessing via Stephen Hayes once again.

I can’t be too critical of Kober here, because he’s working with the material that’s available to him in 2006, and it wasn’t until 2017 that Japanese scholar Yoshimaru Katsuya publicly challenged the Mochizuki Chiyome thing. Even so, it ought to have been obvious to Kober that the material he was working with was not well supported by evidence or transparent about its sources, so it’s a little disappointing that he wasn’t more careful here.

The Kunoichi as Media Figure

By far the most interesting part of Kober’s article is the last couple of pages, which deal with the kunoichi specifically as a media figure:

These more or less accepted historical facts [I’d go with ‘less’ - RT] are as nothing before the media success of imaginary kunoichi and ninjas. The most impressive representations are to be seen in the worlds of video games, manga, and film, but also in some unusual novels. These worlds deal with intimate relations, and they have done a lot to assist the dizzying circulation of ninja-themed works.5

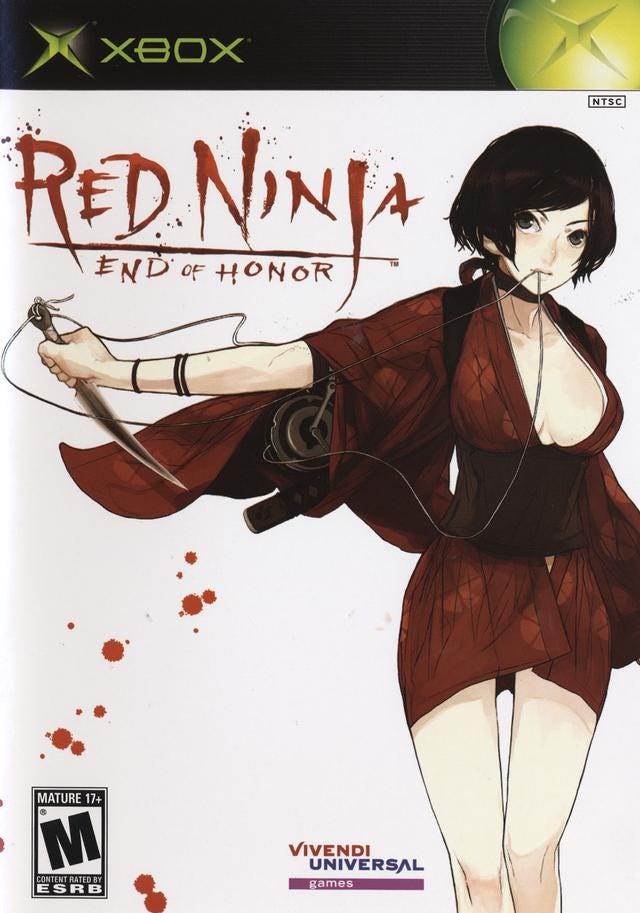

The first such work Kober mentions is a video game released the year before the article, the 2005 Red Ninja: End of Honor for the Play Station 2 and Xbox. It’s only a brief discussion, mostly focusing on the depiction of the heroine of the game, a kunoichi named Kurenai (literally, ‘scarlet’):

Out of curiosity, I looked the game up.

It seems like it was crap. Wikipedia’s discussion points out that it received “generally unfavorable reviews,” and this review suggests that:

The camera is completely useless, the controls are awkward, the platforming is uncontrollable, and the enemies are stupid as well as generic.

On the plus side, you can “perform a vaguely suggestive activity” to entice enemies in close and then kill them. So there’s that.

Kober then goes on to briefly survey a number of other films in which kunoichi appear, notably the 1970s works Lone Wolf and Cub series and 1972 film Zatoichi at Large. He does mention a couple of works by Yamada Fūtarō, but the grand finale is reserved for a 1998 work by the actor/director Ozawa Hitoshi, which Kober refers to by its English title Kunoichi: Lady Ninja:

So, I haven’t seen this, but from the description Kober gives and from the handful of reviews I’ve found on line, it seems like it makes Ninja Lady Magic look like a model of film realism. One line from Kober will suffice, which really should be heard in the original French:

Elles pratiquent des techniques stupéfiantes, comme l’onde de choc du mamelon du sein (nipple shock wave).6

I looked this one up too - pretty much had to, after that summary - and apparently it involves shooting lightning from the kunoichi’s nipples.

Apparently the set-up for the film is that a group of seven Buddhist nuns are attacked by a group of evil samurai, and determine to take revenge. The stress of the attack, seemingly, prompts them to develop magical powers. The film is available with English subtitles, but most viewers appear to have been simply baffled by what appears on-screen. This IMDB review describes it as a “screaming howler of a bad movie” and it has a fairly unimpressive, if unsurprising, score of 38% on Rotten Tomatoes.

The Fear of Fiction

Despite the snarky tone of the above, I actually applaud Kober’s article. It’s unfortunate that he included the dubious historical stuff, but I think he’s to be congratulated for taking on a topic from which plenty of adherents of the cult of the Serious Academic would have run screaming.

The one thing that does bug me, though, is the conclusion Kober draws from all of these ridiculous pulp fiction kunoichi:

To sum up, we are dealing with an extrapolation of the seductress role of the kunoichi, who uses sexual desire and seduction as a weapon, playing on their weakness to become invincible. And this invention of a rich arsenal firing from the sexual organs, eyes, or hair of the combatant, is not out of keeping with the inventiveness of the first Ninjas.7

Perhaps I’m reading this wrong, but Kober seems to be making the argument that the lunatic ‘kunoichi powers’ in all of these movies are, however tenuously, an extrapolation of the actual historical practices of the kunoichi as they really existed.

To which I say: No, they aren’t. They’re simply made up. Why is this point so difficult to grasp?

And so for next time, by way of finally concluding this series on gonzo kunoichi films, I’d like to try to answer my own question and offer some brief thoughts on why this keeps on happening. What is it, in the end, that causes ‘ninja’ writers to fixate so hard on finding a non-existent historical basis to works of pure fiction?

OK, from what I can gather, the ideas are something like this: 1) surrealism is meant to be non-hierarchical, so you don’t know who is supposed to be your ‘superior’; 2) it’s also a ref to the power of the unknown; 3) it’s also a ref to a mystical Christian secret society known as Martinism, where it was the name of a position in that society, the ‘unknown superior.’ I may well have missed something or got some or all of these wrong, for what it’s worth.

Christophe Dauphin, Sarane Alexandrian; ou, Le Grand Défi de L’Imaginaire [Sarane Alexandrian: Or, the Great Challenge of the Imaginary] (Lausanne: L’Age du Homme, 2006), p. 163.

French: “[C]’est surtout à la fin du quinzième siècle que leur histoire commence avec la mort de Mochizuki Moritoki en 1561. Sa veuve, Chiyome Mochizuki fut mise sous la protection du Daimyô Shingen Takeda qui lui imposa de creér et de diriger un réseau secret de Ninjas féminins.” Marc Kober, “Les Ninjas Féminins” Supérieur Inconnu no. 24 (2006), p. 45.

French: “Le choix était entre devenir la proie de tous, être prostituée et mourir, ou devenir kunoichi. Elles étaient endettées et dévouées à leur maîtresse, et prêts à toutes les missions de séduction. On distinguait deux catégories de kunoichi: les «shimma kunoichi» (femme d’un clan, d’une même famille) et les «karima kunoichi» (qui n’appartenaient pas à un clan, mais dont les services étaient louées […]” Kober, “Les Ninjas Féminins,” p. 45.

French: “Ces données historiques plus ou moins avérées ne sont rien devant le succès médiatique des kunoichi et ninjas imaginaires. Les représentations actuelles les plus impressionantes sont visible dans l’univers des jeux vidéo, des mangas, des films, mais aussi de quelques rares romans. Ces univers etretiennent des relations étroites, et c’est en fait à une circulation vertigineuse du thème des Ninjas a laquelle on assiste.” Kober, “Les Ninjas Féminins,” p. 47.

Kober, “Les Ninjas Féminins,” p. 48. For those who have not the tongue, “The female ninja make use of some stunning techniques, such as the nipple shock wave.”

French: “En somme, nous avons affaire à une extrapolation du rôle séducteur des kunoichi, qui utilisent le désir sexual et leur séduction comme une arme, jouant de leur faiblesse pour être invincibles. Et cette riche invention d’un nouvel arsenal issu des organes sexuels, des cheveux ou des yeux de la combattante, n’est pas en désaccord avec l’inventivité des premiers Ninjas.” Kober, “Les Ninjas Féminins,” p. 48.

Here we also have an example of quite a romantic "kunoichi", most likely well trained in singing and dancing in order to get close to potential targets: https://theotherice.wordpress.com/2011/05/01/shinobi-koi-translation/

Definitely check out Kunoichi Ninpocho Yagyu Gaiden, especially if you ever plan on writing an article deconstructing the Yagyu connection to shinobi. The movie is a lot less "ninja magic porn" and more of a "warped chanbara movie with Hong Kong wuxia-esque wire work and the same strange woman ninja magic characteristic of the Kunoichi Ninpocho movies".