Kunoichi means lots of different things to lots of different people.

As we’ve seen over the last few posts, none of the OG ‘ninja’ ‘historians’ - Adams, Draeger, Hatsumi, Okuse, Fujita Seiko - agreed on what the word kunoichi meant, what kunoichi were, or what they did. Depending on the author, kunoichi might refer to women in general, to a fully-trained female shinobi, to infiltration techniques that made use of women, or to a man turning into a woman by disguise or magic. Even after the term kunoichi came to be commonly understood as meaning “female shinobi” during the mid-60s, there was little agreement on what precisely these female shinobi did. Adams thought that female shinobi were seductresses, but were rarely used; Okuse thought that they were so common that ‘ninja’ orgs kidnapped or bought children to raise them as future honey-trap agents. Hatsumi didn’t emphasize the seduction thing so much, writing that kunoichi mostly used their feminine wiles to gain entry to places, while Draeger…well, we’ve seen what Draeger thought.

The point we can take from this is that historical claims about the kunoichi really are all over the place. The only anchor, so to speak, is the ‘ninja manual’ Bansen shūkai’s mentions of kunoichi, but BSSK is very vague as to what kunoichi were and did. And as I’ve argued over and over, BSSK is not a reliable source; there’s no evidence that what it describes ever happened outside of the BSSK author’s imagination.

From this already-dubious starting point, that women might at some point possibly have been used in infiltration operations, would grow a range of specific historical claims about the kunoichi, most of which date only to the 1960s and which seem to be basically fantasy on the part of the authors. So it’s not the case that kunoichi were a real historical phenomenon that was then depicted in literary works, as we might assume. In a pattern that recurs over and over in ‘ninja’ history, the fictional works came first and the historical claims followed after, and the historical claims were mostly based on each author’s imagination.

This is not how you do history; it’s how you write historical fiction.

“The Women of Ninjutsu”

But the fact that something is fictional doesn’t mean it isn’t important. Even if kunoichi didn’t really exist, there’s a lot of mileage in thinking about what kinds of ideas the notion of the female shinobi has been used to advance. One of the uses, especially when presenting to Western readers, is for kunoichi to serve as an example of women’s empowerment, to suggest that anyone male ‘ninja’ could kill, female ‘ninja’ could kill too.

A case in point is a July 1984 article entitled “The Women of Ninjutsu: Beware of Ladies in Black,” from the martial arts magazine Black Belt (you can read it for yourself if you want, thanks to Google Books). Over the years Black Belt would publish all kinds of nonsense on the topic of the supposedly historical ‘ninja,’ and this article is no exception.

The author is Janet Coburn, who appears to have been a student of martial art-type ninjutsu with Stephen K. Hayes. Hayes, as some readers may know, studied under Hatsumi Masaaki and went on to become one of his most prominent disciples; it’s fair to say that a large part of Hayes’ claim to prominence was that he was teaching the ONE TRUE NINJUTSU, which he in turn had learned from the ONE TRUE NINJA MASTER.

Anyway, Coburn’s article, in essence, is an argument for why women should study Hayes’ version of ninjutsu in US dojos:

Perhaps more so than other martial arts, ninjutsu is often thought of as a man’s province. The techniques and philosophy, which have often been grouped with guerilla warfare, espionage, and assassination, at first do not seem likely to appeal to many women.

And yet…

[…] Stephen K. Hayes, the first non-Oriental to be awarded the title of shidoshi…feels the so-called ninja “warrior path” is appropriate for women, and his wife, Rumiko Urata, a black belt in ninjutsu, agrees. In his book The Ninja and their Secret Fighting Art (Tuttle), Hayes relates the history of ninjutsu and the roles that the kunoichi played. There were two basic types of kunoichi. Karima kunoichi were not ninja family members but were hired as needed…Maids, mistresses, entertainers, and prostitutes could often gain access to the enemy…

No mention of poison vaginas, though. Can’t think why.

Actual members of ninja families were called shimma kunoichi, and were trained by a male kantokusha (commander). Since the ninja usually came from rural families or clans, the women were involved in protecting the families right along with the men… The ancient ninja believed women had more highly developed psychic powers than men. Hayes notes that when the ninja family commanders discussed combat plans or tactics, they would always include the women because of their intuitive grasp of the situation. Although the concept of “women’s intuition” is considered today to be largely a myth, Hayes observes that women today may have more motivation to develop their latent psychic skills because they have to consider any means for overcoming size and strength disadvantages they may encounter in fighting situations.

Woof. There’s a lot to unpack here.

Separate But Equal, Ninja Version

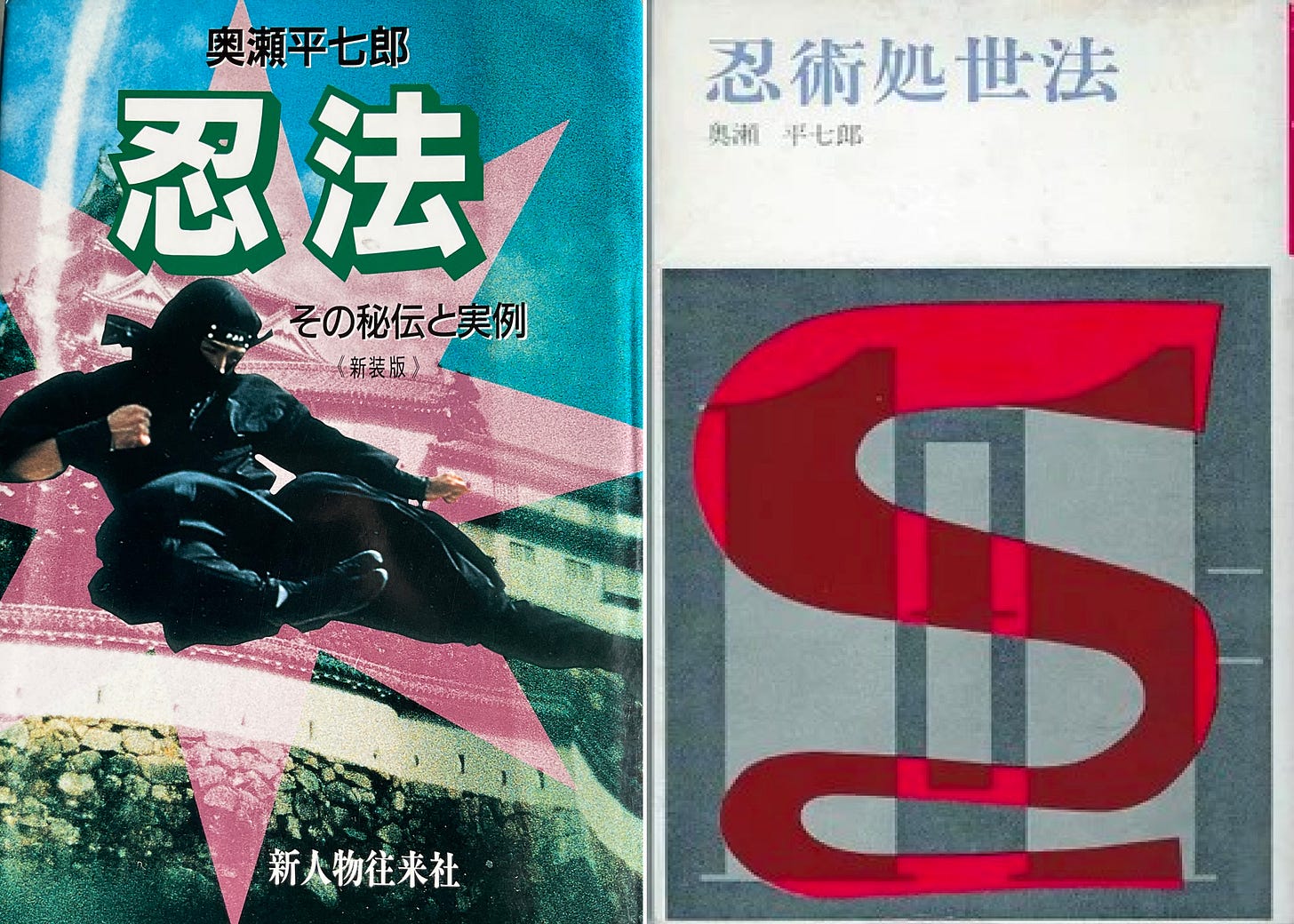

First is the claim about there being two types of kunoichi, shimma and karima, the first of whom were higher status full-time female shinobi and the second of whom were basically disposable labor.1 This claim is unusually specific, which leads me to think that it must have a specific source. Sure enough, it does - it’s our old friend Okuse Heishichirō, who makes this claim in two of his 1960s books, How To Get Ahead Using Ninjutsu: Ninja Arts for Corporate Workers and Ninja Arts: Secret Teachings and Real Examples.2

The graphs Okuse uses are 真間 (supposed to be shimma) and 仮間 (same for karima), which mean something like “true use” and “temporary use,” respectively.3 In neither book does Okuse give a source for this fairly concrete claim about kunoichi practice, though. I can’t find anything resembling this in Bansen shūkai, and since BSSK is the only premodern military manual that mentions kunoichi as far as I know, I have no idea where the shimma/karima thing comes from. My best guess is that the terms were Okuse’s own modern descriptions of how he thought kunoichi operated and Hayes slightly misunderstood what Okuse was saying, coming away with the mistaken impression that shimma, karima, and kantokusha were terms used in the medieval era. The reasons why I think this are a bit technical, so I’ll explain them in a footnote and you can skip it if you’re not interested.4

The rest of Coburn’s piece, about psychic powers and women’s intuition, is definitely from Hatsumi, since it’s virtually identical to the claims about kunoichi in Hatsumi’s 1981 Ninjutsu: History and Tradition. The “psychic powers” bit strikes me as worth mentioning, if only because it’s obviously weird. As you’ll see if you read the article for yourself, Coburn attempts to work around the weirdness by saying that, well, maybe this belief in women’s psychic powers was actually based in something real, that “psychic powers” were really an unconscious ability to read faces.

It’s possible, now that I think about it, that Hatsumi’s claims about how ‘ninja’ believed kunoichi to have psychic powers could be a very distorted echo of the fictional kunoichi in 1960s media. Early ‘60s female ‘ninja’ often had literal magical powers which allowed them to hold their own against male ‘ninja,’ like the female ‘ninja’ Kagerō in Yamada Futarō’s Basilisk, whose magical power is that her breath becomes poisonous when she’s sexually aroused.

(Wait, hold on - is that where Draeger got it?)

The Gender Politics of the Kunoichi

So although Coburn’s article doesn’t offer any reliable historical information, it’s still interesting on a meta-level. It’s a great example of how most of the kunoichi lore that reached English-speaking audiences can be traced back to the unsupported claims of just two guys, namely Hatsumi Masaaki and Okuse Heishichirō. And it also shows how the kunoichi concept, in a Western context, could be spun and adapted to become basically ‘gender-equality ninja style,’ here in the interests of boosting enrollment at ninjutsu dojos throughout the US.

The thing is, though, it’s really debatable just how far kunoichi discourse in its original Japanese context was about gender equality; in some ways, it was much more about reinforcing conventionally gendered hierarchies. By way of developing this point, for the next post I’d like to think a bit more concretely about the gender politics of the kunoichi as a whole, especially the idea that the historical kunoichi might function as an expression of women’s empowerment.

It’s a little unsettling how similar this is to the tenured/non-tenured distinction in US academia, actually.

Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei (1964; my edition 1995); Ninjutsu shoseihō: Sarariman ninpō (Yomiuri Shinbunsha, 1963). I’m pretty sure Hayes read the former, for the reasons outlined below.

Ninjutsu shoseihō, as you may have guessed from the title, is a self-help book for corporate Japanese workers that supposedly tells them how to use ‘ninja’ techniques to suck up to the boss, get raises and promotions, etc. It’s exactly as ridiculous as it sounds, and what makes it even more hilarious is that Andrew Adams mentions Ninjutsu shoseihō in his Feb 1967 article in Black Belt magazine, seemingly with no idea what the book was about. As you’ll see if you look at Adams’ article, Adams mis-translates the book’s title as “Mental Preparations” and appears to have missed the “salaryman” bit of the subtitle. Shoseihō doesn’t mean “mental preparations” - it means something like “how to get ahead in life.”

Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei, p. 130; Ninjutsu shoseihō p. 149. Not that it matters all that much, but the superscript notations in the latter suggest that Okuse intended the graphs 真間 and 仮間 to be read as shinkan and kakan rather than shimma and karima.

The first reason is that etymological dictionaries suggest that kantokusha (translatable as ‘director,’ ‘overseer’) doesn’t appear before the mid-to-late 19th century, centuries after the supposed ‘ninja’ heyday. The Dictionary of the Japanese Language (Nihon kokugo daijiten), for instance, gives the earliest use of the word kantokusha as being in Japanese legal jargon from 1896. (It’s possible, of course, that the term was in use before then but not common.)

The second reason is that Okuse uses different terms for the supposed ‘handler’ role in Ninpō (p. 130) and Ninjutsu shoseihō; it’s kantokusha in the former but shijutsusha 施術者 (‘facilitator’) in the latter (p. 149). If kunoichi handlers were in fact called kantokusha in medieval times, you’d expect Okuse to use the same phrase across both books.

To make the point a bit clearer: imagine I were to describe a medieval European tax collector as “the IRS guy,” but a Japanese reader then misunderstands me and records that medieval tax collectors actually were called “IRS Guys” in their own time.