In the previous post I documented how prominent ninja historians Donn Draeger and Stephen Turnbull had committed the same horrible error by using a children’s book as a primary source (bad) and then failing to notice that the same book explicitly said that the protagonist of their story was a fictional character (even worse).

I wish I could write this off as an isolated, sloppy error. Unfortunately, though, in Turnbull’s case it’s not the only error of its kind even in the same book. Today we’ll be taking a close look at how Stephen Turnbull handled the story of the ninja Hachisuka Tenzō, and asking some pointed questions about what Turnbull thought he was doing with it.

Hachisuka Tenzō: When You’re in a Hole…

In his 1991 Secret Warrior Cult and his 2003 Ninja: AD 1460-1650, Stephen Turnbull includes this story as one of several examples of historical ‘ninja assassinations’:

The well-defended Takeda Shingen had an attempt on his life made by a ninja called Hachisuka Tenzō sent by Oda Nobunaga. Having failed in his attempt Tenzō was forced to flee, and the Takeda samurai pursued him into a wood, where he concealed himself from the moonlight among the shadows of the trees. A spear thrust from his pursuers caught only his costume, and he subsequently evaded capture by hiding in a hole in the ground which he had already prepared.1

The source isn’t clearly cited in either of Turnbull’s books, but it has to be Hatsumi Masaaki’s children’s book Ninja Skills Illustrated again, because the major details from both stories match exactly with Hatsumi’s account (with a couple of exceptions, as we’ll see), and we already know that Turnbull was using Hatsumi’s book as a source for his stories.

As with the Kirigakure Saizō story in the previous post, I’ve tried to find other mentions of Hachisuka Tenzō and have been unable to do so. There is a character named Watanabe Tenzō from the village of Hachisuka in the historical novel The New Chronicle of Lord Hideyoshi, published by the writer Yoshikawa Eiji between 1939 and 1951, so it’s possible that Yoshikawa Eiji’s novels were Hatsumi’s inspiration for the story.2

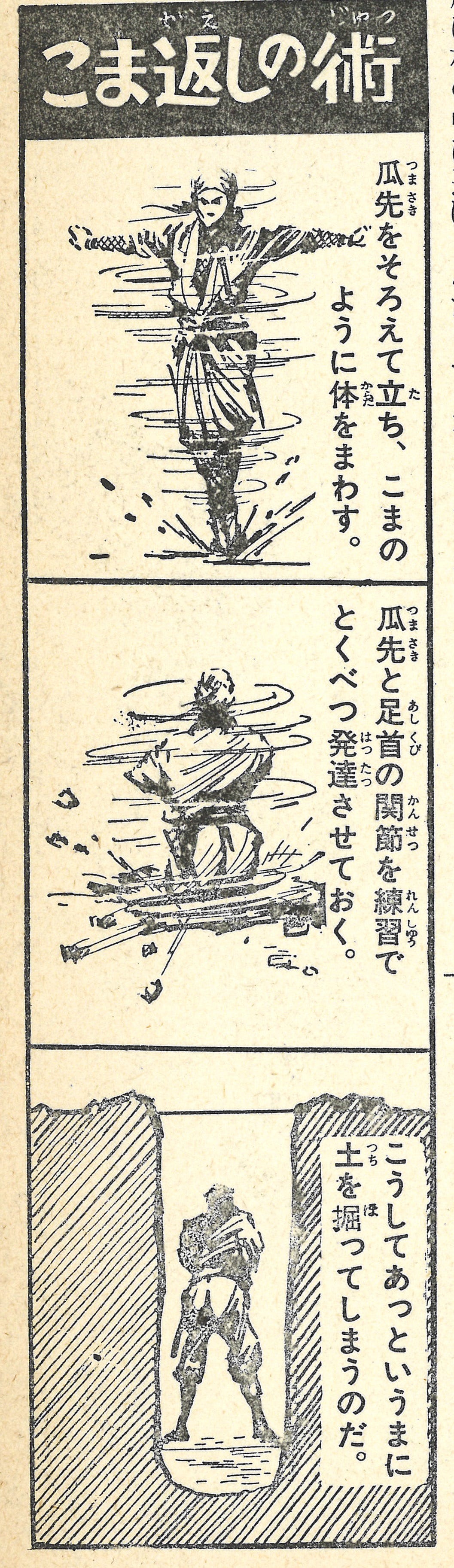

What’s significant, though, is the way in which Turnbull edits the story from Hatsumi’s original for his English-language readers. Turnbull’s account says that Tenzō “prepared” a hole in the ground in advance, presumably by digging with a shovel or some kind of cool ninja tool. That’s not what happens in Hatsumi’s original version, where the digging is a lot more dramatic. According to Hatsumi, what Tenzō did was to spin himself around so fast that he became a human drill, and “in a matter of seconds” (atto iu ma ni), had dug a hole in the ground large enough to hide in:

This, according to Hatsumi, is the koma-gaeshi no jutsu, the ‘rotating drill’ ninja technique.3

OK. Look, I’m not an engineer, but…I don’t think you can do that.

You Spin Me Right Round, Baby, Right Round

Not content with this amazing feat, according to Hatsumi, Tenzō’s mad ninja skillz allowed him to almost instantly give off huge amounts of sweat. So it was that, when Tenzō’s pursuers looked down into the hole he had dug, there appeared to be water at the bottom, and thus did Tenzō complete his escape.

I invite you to draw your own conclusions as to the factual status of Hatsumi’s story.

In contrast to Turnbull’s version, Hatsumi doesn’t specifically say that Tenzō had prepared the hole in advance. I think a reasonable reading of the story, given the mention in the illustration that the ‘rotating drill’ jutsu could dig a hole “in a matter of seconds,” is that Tenzō dug his hidey-hole right there in the heat of the chase.

I hope I don’t need to say this, but it should have been obvious to Turnbull that there was no way this story could be true as Hatsumi had presented it. The sensible thing would have been to move on and find another story, especially since I doubt Turnbull had any other corroborating source for the story apart from Hatsumi. That was not what Turnbull did, as we can see. What Turnbull presents to his English readers is a subtly edited version of the story that omits these amazing ninja techniques, and instead presents the comparatively mundane claim that Tenzō simply dug a hole in, one assumes, the normal way.

Why did Turnbull make these edits? I don’t know. Maybe Turnbull realized that the ‘human drill’ part of the story couldn’t possibly be true, and that if he included that element most of his readers would spot it for the tall tale it clearly is. (To say nothing of the ‘ninja sweat’ thing.) So he edited out the obviously ridiculous bits, changing just enough of the story that it could appear plausible as history. Maybe Turnbull thought that there was probably a real ‘ninja’ story in there somewhere, even if Hatsumi’s ‘human drill’ part was fantastical, so he edited the story to be closer to what he thought the ‘real’ story might be. Again, I don’t know for sure. The above is speculation, and I have no way of knowing what Turnbull may have been intending to do.

I can say, though, that the effect of Turnbull’s intervention is to change a story that’s obviously fictional in the Japanese into one that reads like something that really happened in the English. These edits, in other words, completely change the story’s facial plausibility, denying the English-language reader the clues in the original that the story couldn’t possibly be true as presented. This sort of thing strikes me as pretty questionable in any work of history, let alone one written for general audiences. And as I’ve noted, Turnbull then repeated the same story in his 2003 book.

If it was indeed the case that Turnbull reasoned that there must be a real story in there somewhere, he would have been in good company, since this is a common assumption among ninja historians in general. I like to call this the ‘kernel of truth’ argument, and it posits that yes, a lot of stories about ninja may be fictional, but they still point to the underlying truth of the ninja throughout history. This is more or less how Draeger frames his ninja stories, but it’s not at all how Turnbull presents his work to his readers. Quite the contrary, in fact; on the first page of 2003 Ninja: AD 1460-1650, we read:

[…] I have decided to ‘play it straight.’ Any references to ninja that could fly will be identified as the myths they are. Quotations from written accounts of ninja exploits will be confined to chronicles that are respected for their accuracy.4

Yeah. I’ll let that stand without comment. You will no doubt have your own views as to whether Turnbull’s description of his methodology is accurate.

One of the take-home points from this, I think, is that readers should regard any specific historical claim in Draeger and Turnbull’s ninja books as suspect unless clearly proven otherwise.5 This sort of thing is particularly insidious because, as I’m sure you realize, the intended audience for these books is general readers interested in Japanese history. By definition general readers don’t have the skills or experience to identify and check the underlying sources for themselves, so they have to trust that the writer has a reasonable basis for his claims and is representing his sources accurately.

Unfortunately, as I’ve said, these kinds of errors are endemic to English-language ninja writing as a whole. This alone is enough to render almost all of English-language ninja history useless to its intended audience, because you cannot know if what you are reading has a basis in documentary evidence or is taken from a 1964 children’s story book.

Hachisuka Tenzō 蜂須賀天蔵; Takeda Shingen 武田信玄 (1521-1573); Oda Nobunaga 織田信長 (1534-1582). The latter two were real individuals, as the dates indicate. The story appears in Secret Warrior Cult p. 52 and AD 1460-1650, pp. 30-31.

New Chronicle of Lord Hideyoshi is Shinsho Taikōki 新書太閤記, by Yoshikawa Eiji 吉川英治 (1892-1962). Yoshikawa was a hugely popular and influential historical novelist, and his Shinsho Taikōki is available in English translation as Taikō: An Epic Novel of War and Glory in Feudal Japan.

Hatsumi, Ninja Skills Illustrated, p. 97.

Turnbull, Ninja AD 1460-1650 (2003), p. 4.

At least, Turnbull’s works prior to 2015. As I noted in the welcome post to the newsletter, Turnbull has issued something of a mea culpa since 2015 about some of the less impressive aspects of his earlier work. I plan to address this in a future post.

(For those who don’t get the ‘Spinjitzu’ reference in the subtitle - the animated Lego kids’ show Ninjago: Masters of Spinjitzu features a group of young ninja, among whose special skills is the ability to spin incredibly fast and create powerful tornado-type effects. Who knows, maybe they got the idea from Hachisuka Tenzō?)