A Japanese dude dressed in black with his face covered is a ninja. This is so obvious it hardly needs to be said. AI image generation knows it, the internet knows it, my daughter knows it when drawing ‘ninja kitties,’ as she does these days. When navy blue-clad assassins with their faces covered come after Tom Cruise’s character in The Last Samurai, the film doesn’t even bother using the specific word ‘ninja,’ because in 2003 literally everyone in the audience knows who these guys are without any explanation.

But did ‘ninja’ really wear masks and all black? Well, sure, the ‘ninja’ is a modern fictional construct, so yeah, he can wear whatever he wants.

What you’re asking, if I’m going to be less of a smartass academic dick about it, is whether there’s any evidence that the historical shinobi wore the classic black outfit we see in most fictional depictions of ‘ninja.’ Like the ‘how did ninja use shuriken?’ issue, this question has been done to death in online debates, many of which are remarkably free of anything resembling historical evidence. (Good old Quora, a wonderfully reliable source of free-range horseshit.) You’re also likely to see the claim that blue would be better camouflage than black in night-time, because black is, like, too dark, dude. (“And the answer is none. None more black.”) That last one actually has some textual support for it, since it appears in a (much later) military manual supposedly discussing stealth techniques, but we’ll get to the ‘ninja manuals’ in due course.

If we approach this as an historical question – which is usually how it is framed – then the discussion will be very short and not particularly interesting, because the answer is:

No, there is no evidence that shinobi wore black.

Remember, we know very little about the historical shinobi because of how few and limited the sources are, but no source mentions them wearing anything like the classic black outfit we know so well. So like many things relating to ‘ninja,’ if we take this as an historical question there’s basically nowhere to go and that’s the end of the discussion.

But remember, the ‘ninja’ is primarily a literary construct, not an historical one. If we approach the black outfit instead as an artistic motif - in other words, as an element in literature or art history - then things become a lot more interesting. Doing that allows us to ask: where did the image of the black-clad ‘ninja’ come from, and how did it get so overwhelmingly associated with a modern fictional construct?

Kabuki Warriors

If you’re at all familiar with English-language ‘ninja’ lore, you’ve probably heard the claim that the classic black costume may derive from the kuroko, who are black-clad stage-hands in various forms of early modern Japanese theater.1 This claim is on one of the National Diet Library’s English-language pages about ninja as well as the Wikipedia page on kuroko, for instance, with the inevitable Stephen Turnbull cited as the source on the latter.

The first thing to say about this claim is that it’s anachronistic. The NDL page claims, for instance, that:

It is thought that the black costume was a stage direction device to immediately identify a character as a ninja.

This claim is very misleading, though, because the concept of the ‘ninja’ is basically a 20th century one, and almost none of the figures in black in the prints we’ll look at are actually ‘ninja’ or even shinobi as most readers would understand the term. So hanging the label of ‘ninja’ on figures in black is badly ahistorical, because it’s reading a 20th century social and literary archetype into a context where it didn’t exist.

Another claim I’ve seen is that the kuroko are supposed to be symbolically invisible on the stage, so the costume is a kind of way of symbolizing that someone is also invisible or not to be noticed to a viewer or an audience. I’ve never really understood that argument, because the black costume is very conspicuous and the figure is usually the focus of the print in question.

Like a lot of ‘ninja’ history, the argument that the black outfit comes from the theater tells us a lot more about what’s going on here than most advocates of the historical ‘ninja’ probably realize. What these claims are implicitly conceding is that the dominant image of the supposedly historical ‘ninja’ derives entirely from the world of fiction. This is, of course, very on-brand for ‘ninja’ history in general.

My guess is that the image of the black-clad ‘ninja’ has a lot more to do with pictorial art than the theater. The two are often connected, because it was quite common for famous actors or play scenes to be depicted in picture form as promotional or fan material. But equally, a lot of the pics of dudes in black that appear in ‘ninja’ histories are illustrations from works of prose fiction. So the theater isn’t the only source, and in any case, it’s the picture that actually gets the image of the black costume out there, not the play itself.

Since it makes more sense to look at the images themselves first and foremost, let’s do exactly that. We’ll be working mostly with late-Edo and early Meiji pictorial art, which would mean works produced between about 1700 and 1900 or so.

Here Come the Men in Black

So, let’s not bury the lede:

The black outfit and/or hood is a literary and artistic convention, indicating to the viewer that a character is doing something they don’t want other people to know about.

That’s it; it has NO SPECIFIC CONNECTION TO ‘NINJA.’ It’s also a fairly common visual convention in pictorial art of the 18th through 20th centuries, meaning that the black outfits are worn by dozens and dozens of characters who would never be considered ‘ninja’ in any reasonable definition of the term, even if the concept had existed at the time.

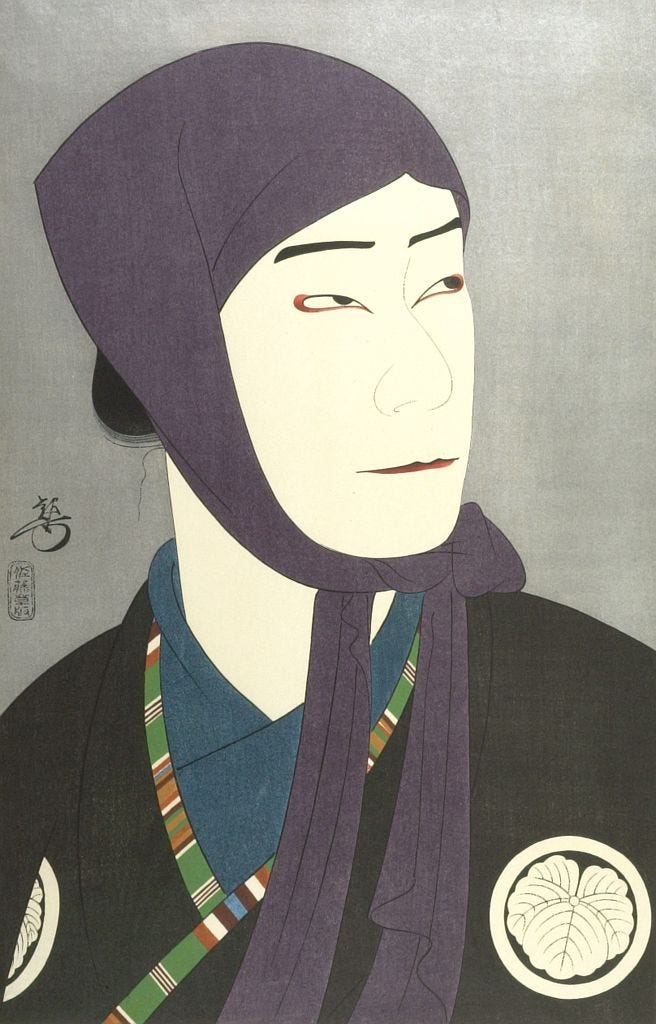

Let’s look at a few concrete examples, some of which have appeared in English-language ‘ninja’ histories and some of which are my own selections. One of my personal favorites is this one, which I first came across in Stephen Turnbull’s 1991 Ninja: The True History of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult:

This print is almost the first thing you see when you open the book, facing the frontispiece, and it’s presented there without caption or explanation. Since Turnbull’s book is about ‘ninja,’ I imagine most general readers would look at the print and come away with the initial impression that this is a print from pre-modern Japan depicting a ‘ninja.’

It’s not. The print is from around 1922 and is a depiction of Kamiya Jihei, a fictional character from the mid-Edo play The Love Suicides at Amijima (Shinjū ten no Amijima, first performed 1720).2 Is Kamiya Jihei a feared and skilled assassin? No, he’s a paper merchant, and the reason he’s wearing the black hood is that he’s headed to Osaka’s brothel district to visit his courtesan girlfriend. He’s wearing a black hood because, like many visitors to the brothel districts, he does not anyone to know what he is doing.

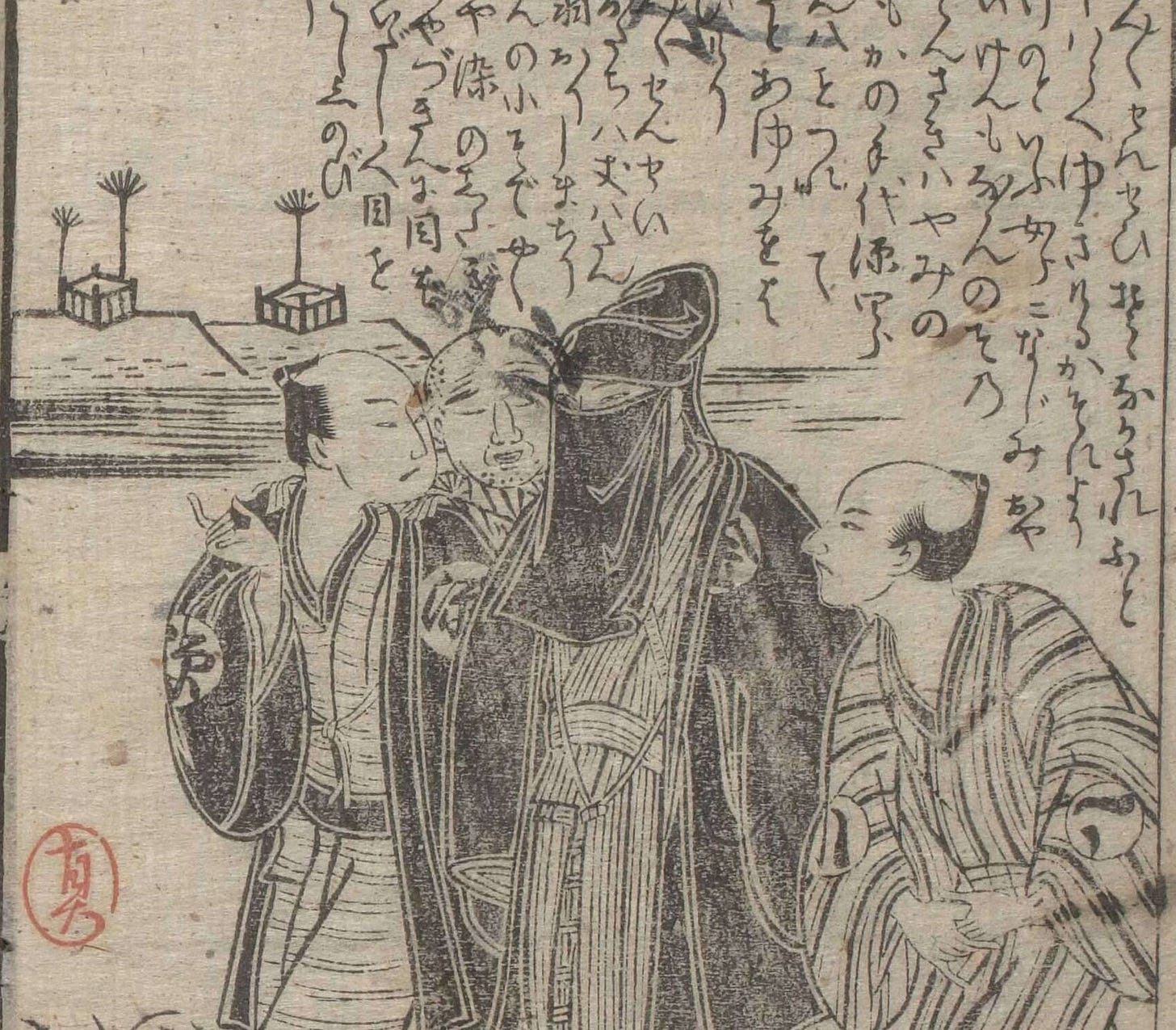

Here’s another print along the same lines. Presented without any context, most English-speaking readers would probably assume that this is a ‘ninja’ on a mission, carrying a sword for assassination purposes. Could he, perhaps, be readying a poisoned shuriken dart in his hand in preparation to strike?

Nope. This is a scene from the same play, The Love Suicides at Amijima, and it’s Jihei’s brother Magoemon, who has come to the brothel district to try to bring his dissolute sibling home lest he bring shame and ruin on the family.3 Magoemon is covering his head for the same reasons his brother did, and the thing in his hand does contain a lethal poison, because it’s a tobacco pipe - he’s stopping to have a quick smoke while he’s waiting. You can see the full scene (it’s a triptych, meaning a three-paneled scene) here.

Black is the New Black

Hopefully the point is clear, then: people in Japanese prints could wear concealing black garb for any number of possible reasons, most of which had nothing to do with ‘ninja’ in any sense. Turnbull knew that the 1922 print was a paper merchant and that black hoods could be worn for tons of reasons way back in 1991, by the way, since the caption to the Kamiya Jihei print when it appears for the second time in Secret Warrior Cult names the figure as Kamiya Jihei and states that:

The wearing of a covering for the head was a practice by no means confined to ninja.4

Well OK, fair enough, but then a lot of the prints in the book are irrelevant to its discussion, aren’t they? What’s Kamiya Jihei doing in the book if he’s not a ‘ninja’ – why not stick to prints of people who are? And of course, putting this picture as the first illustration with no explanation seems like a fairly cheeky attempt to pull the wool over the reader’s eyes. Not least because as I’ve noted, Turnbull was fully aware of what the print actually depicted.

It kind of says something when the first illustration in a book about ‘ninja’ has nothing at all to do with ‘ninja.’

What about this one? A captured ninja being taken for execution? He’s even got the full face-covering, just like we’ve come to expect:

Nope. This is Kinbei, the protagonist of Koikawa Harumachi’s 1775 fictional story Mr. Glitter ‘n’ Gold’s Dream of Splendor (Kinkin sensei eiga yume, 1775), who (in his dream) has become fabulously wealthy and is on his way to the brothel district of the Yoshiwara in the city of Edo.5

Black hoods aren’t confined to visitors to the brothel districts, in case you’re wondering, as we see in this next Edo-period print. This one I have to link to rather than display, as apparently it’s copyrighted, so click this link to go to the National Institute for Japanese Literature archives and scroll to cell 17 in the viewer on the right-hand side of the main frame.

It looks promising, doesn’t it? We have two figures wearing black ‘ninja’ masks with their swords drawn, and on the right, we see - no doubt - two hapless victim of the ninja, pleading for their life before these merciless killers strike them down..?

Yeah, no. This one is from the satirical (and fictional) story Grilled and Basted Edo Playboy (Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki, 1785).6 The masked figures are robbers, who mug the main character Enjirō and his courtesan girlfriend and steal their clothes, leaving them to walk home in their undies, as you can see in the next cell (#18).7 To cap it all, it later turns out that the ‘robbers’ were actually Enjirō’s dad and brother, who disguised themselves to pull off a kind of ‘scared straight’ operation because they disapprove of Enjirō’s playboy lifestyle. Again, there’s no reasonable definition of ‘ninja’ under which the guys in black would qualify.

So let me say it clearly: You cannot casually find a figure in a black hood in an Edo-era print and say “that’s a ninja,” because (a) that’s an ahistorical reading, and (b) there are tons of guys in black who are not remotely close to ‘ninja’ in the modern sense, or even to the historical shinobi.

Let me offer some advice, then: If you’re going to present black-clad figures in Japanese prints to English-speaking audiences and tell the reader that they’re ‘ninja,’ you better be damn sure you can prove the figure is indeed a ‘ninja’ in the usual definition of the term. Otherwise you will mislead your reader, who, remember, usually doesn’t have the language skills or background knowledge to know what they are really looking at.

We haven’t even scratched the surface of all the bad art history going on with pictorial depictions of the supposed ‘ninja,’ by the way. Stay tuned for our next few episodes, where I’ll address some of the other ways in which ‘ninja’ historians habitually misread and abuse Japanese pictorial art.

Kuroko 黒衣

Kamiya Jihei 紙屋治兵衛; Shinjū ten no Amijima 心中天の網島. Ten no Amijima is a very famous play by Chikamatsu Monzaemon 近松門左衛門 (1653-1724, aka the ‘Japanese Shakespeare’). It was first performed at the end of the lunar year in the fifth year of the Kyōhō era 享保 (1720), but the date would have been the first few days of 1721 if reckoned using the Gregorian calendar, so you’ll see both 1720 and 1721 for the date of first performance.

Magoemon 孫右衛門

Turnbull, Secret Warrior Cult (1991), pp. 98-99.

Kinbei 金兵衛; Koikawa Harumachi 恋川春町 (1744-1789); Kinkin sensei eiga yume 金々先生榮花夢. Harumachi did both the text and illustrations for the story, by the way.

Edo umare uwaki no kabayaki 江戸生艶気樺焼

Enjirō 艶二郎, which literally means something like “lustful second son,” in case it matters.