The True Ninja's Hood is Dyed With the Blood of His Enemies

Or Plant Dye. Actually, It's Plant Dye.

Last time around we noted that the idea that ‘ninja’ wore black hoods probably started with the work of the early 20th century ‘ninja’ writer Itō Gingetsu. In his works published between 1909 and 1937, Gingetsu included numerous illustrations of figures wearing the ‘eyes-only’ head covering that postwar audiences would come to associate with ‘ninja.’ Since these figures were being presented in the context of his argument for what he called ninjutsusha as specialist spies or infiltrators, it’s clear that these images are intended to be taken as depictions of essentially modern ‘ninja,’ unlike the Edo-period prints we’ve been reviewing.

I also noted that Gingetsu says in his 1917 The Ultimate Meaning of Ninjutsu (Ninjutsu no gokui) that ninjutsu-sha carried a number of specific tools, among which was a three-foot length of cloth that could be wrapped around the face when sneaking in somewhere. His source for this claim is the Shōninki, a military manual from around 1681. So let’s take a look at how Gingetsu uses the Shōninki, then move to consider how far we can treat Shōninki and similar ‘ninja manuals’ as reliable sources of information.

The Ninja Scarf - Stylish AND Practical!

According to Gingetsu, the ninjutsusha habitually carried six specific items on their missions:

a woven bamboo hat

a rope and grappling hook

a writing-stick

medicine

a length of cloth three feet (shaku) long

a split bamboo tube [for containing coals]1

Gingetsu is quite transparent on his source for this - it’s derived from a section of the Shōninki. In Japanese, these items would be amigasa (あみ笠), kaginawa (かぎ縄), ishifude (石筆), kusuri (薬), sanshaku tenugui (三尺手拭), and uchitake (打竹).

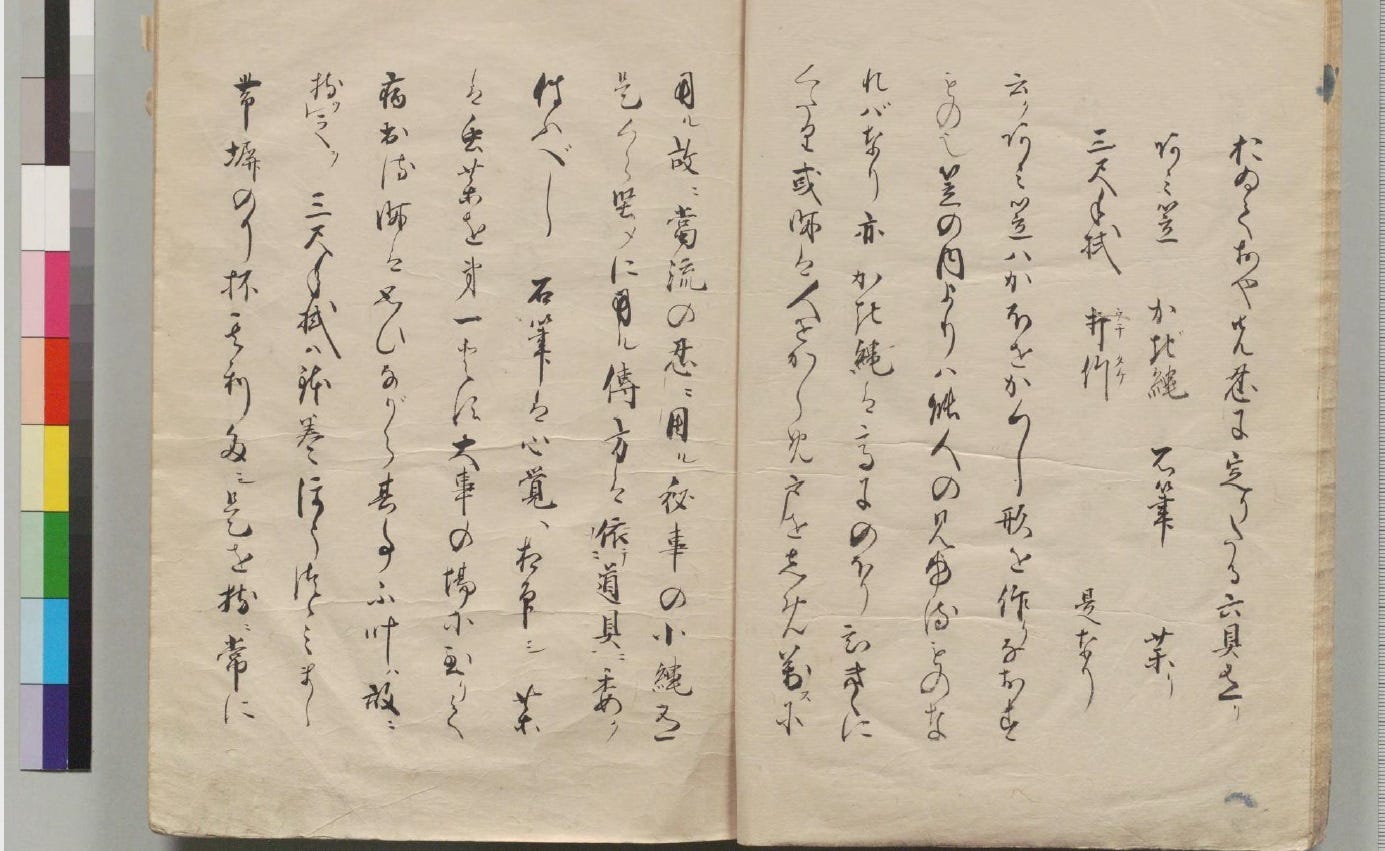

Here’s the National Diet Library’s copy of the original text of the Shōninki. The list is on the right-hand side in the indented area, and if you can read Japanese, you may just about be able to recognize the characters in their calligraphic style or variant kana form:

Gingetsu’s account in Ninjutsu no gokui of how these items were used seems to follow Shōninki pretty closely, so he definitely read it. On the left-hand side of the image above, in the Shōninki’s discussion of the items, it says that the three-foot scarf can be wrapped around the head in the style of a headband or wrapped around the face (or literally, cheeks. This may be either the ‘bonnet’ or ‘eyes-only’ style of face covering I described in the last post - it’s not entirely clear from context).2 The text under discussion starts about a third of the way down in the second column from the left and says that:

the three-foot scarf has many uses - it can be worn as a headband or wrapped around the cheeks, used as a second belt, or used to climb over walls.

三尺手拭は鉢巻、ほうつつみ、まし帯、塀のり抔利多し。3

So clearly, this text from 1681 was where Gingetsu was getting the idea that ninjutsusha wrapped cloth around their faces when on infiltration missions, and it’s worth noting that this idea appears in all three of Gingetsu’s 1909, 1917, and 1937 works on the topic. So I’d have to disagree with Turnbull’s remark in his 2017 book that Gingetsu “made little use” of Shōninki.4

A Guide to Reading those ‘Ninja Manuals’ Critically

As we discussed last time around, Gingetsu specifically says that the ninjutsusha’s clothing should not be black, and this is also something he appears to be taking from the Shōninki. Gingetsu further states that the ninjutsusha’s three-foot scarf was dyed a kind of reddish color using a plant-based dye known as suhō-zome.5 That last detail I’m not sure where he got, as I can’t find a specific reference to suhō-zome in the Shōninki, though the latter does say that one of the possible colors for shinobi attire is a brownish tan color.

So all of this appears to corroborate what we thought we knew, that shinobi did not wear black. But at the same time, this doesn’t exactly seem to bust the myth of the classic ‘ninja’ image, because Gingetsu’s writings suggest that shinobi did indeed wear something close to the ‘ninja hood’ that we’re all familiar with from modern pop culture. And Gingetsu clearly isn’t just making this up - he has a textual source from the mid-Edo period that really does say that shinobi wore cloth to cover their face.

Bearing this in mind, then, what I’m going to lay out in the next few paragraphs is a method for thinking critically about Edo-period ‘ninja manuals’ such as Shōninki. It’s a roadmap - or if you prefer, a set of questions - that ‘ninja’ historians since the 1970s or so appear to have carefully avoided using, for reasons that I’m sure will become obvious.6

For context, if you’re new to the field, an awful lot of what you are likely to see in Japanese and English-language media as ‘authentic ninja lore’ derives from the pages of military manuals written during the Edo period (1600-1867) on the topic of shinobi operations. This 2018 article about what shinobi supposedly ate is a great example of the genre, in that it’s taking passages that appear in 17th and 18th century manuals and presenting them uncritically as established fact.7

The first question you should be asking yourself as a critical historian reading a ‘ninja manual’ is a very simple one:

Does this stuff have any connection to reality?

As I said above, this is a question that ‘ninja’ historians in Japan and in the English-speaking world really, really don’t want to have to deal with. News websites know that they get more clicks by presenting this stuff uncritically, and writers like Cummins are presumably also aware that they sell more copies and get a wider audience if they present these texts as the SECRET WISDOM OF THE NINJA, while staying well away from the question of whether the contents are reliable or not.

Myself, I think the appropriate attitude toward these materials is one of skepticism. Let me explain why, and also provide a quick-and-dirty lesson in some basic principles of textual scholarship.

Point #1: Most of These Texts were Written Decades, Sometime Centuries, After the End of Regular Warfare in Japan

It’s a very basic principle of historical scholarship that the further in time a text is from the events it describes, the less reliable it probably is. Most of us were taught this principle as early as high school or even middle school; we wouldn’t take a 1900 painting of the first Thanksgiving as a reliable depiction of the events in question, for instance, because the intervening centuries provide layer upon layer of misconceptions and distortions for the painter to draw on.

So the same basic principle applies here, since the two big dogs of ‘ninja manuals,’ the Shōninki (1681) and the Bansen shūkai (1676), were both written during a time of peace more than seventy-five years after the end of the Warring States period.8

That last bit, the ‘time of peace’ part, is important, because popular audiences often have a very hazy idea about ‘samurai history’ as it played out in Japan, kind of assuming that the samurai were pretty much always fighting until they stopped some time in the early 20th century, or something like that. This could not be further from the truth; with a couple of exceptions in 1615 and 1637-8, there were no more wars to fight for virtually the whole of the Edo period, from 1600 to 1867 or so.

So for one, the writers of these ‘ninja manuals’ would have been fully aware that there was next to no chance that the tools and techniques they describe would ever be put into practice in real life. If you have ever read an English-language martial arts manual that purports to teach you, say, Advanced Shōtōkan Karate or Wing Chun Kung Fu (or whatever), you’ll probably be aware that such books can contain techniques that are, shall we say, a little fanciful. The authors of such books are, of course, free to include ludicrously impractical ways of fighting, partly because they know that the contents will almost certainly never be put to the test outside of a martial arts gym.

Another important point is that almost from the very moment that the samurai stopped being warriors, they began to romanticize and re-imagine their past as fighting men. To some extent the samurai had always been romanticized - we noted that in our discussion a month or two back about the Taiheiki and the Tale of the Heike - but it really took off in the Edo period.

We have to bear the above points in mind as we assess these ‘ninja manuals,’ then. Their authors were not old enough to have had any personal, life-or-death experience of the techniques of the shinobi they were discussing, and they were free - maybe even incentivized - to invent, romanticize, and embellish a little (or a lot) if they chose.

So that’s the first thing to bear in mind - the historical and cultural context for these texts isn’t exactly discouraging to the inclusion of second-hand knowledge and outright fantasy. The second thing:

Point #2: Very Little in these Manuals Can be Corroborated

One point you will immediately notice in reading through a ‘ninja manual’ is that the author(s) almost never give specific historical examples of these techniques being used. There is, as Stephen Turnbull notes in Unmasking the Myth, one real-life shinobi operation referred to in the pages of Bansen shūkai, but the author gets quite a few of the details wrong and definitely seems to be working with second or third hand accounts of the operation.9

A good principle of historical scholarship is that as far as possible you should never work with only one source; you need to corroborate and cross-reference multiple sources to assess their reliability. What we would ideally want, then, would be some kind of external account that described an infiltrator in a tan-colored hood with only his eyes showing, who threw shuriken at the guards, and so on and so on. Unfortunately, there aren’t any such accounts, and this is why we can’t view Gingetsu’s claims about head coverings as historical fact - because we have no evidence that what the Shōninki describes was actual shinobi practice out in the real world.

As a further example, Bansen shūkai contains a couple of famous passage about kunoichi, the supposed ‘female ninja’ interpreted in various fantastical ways by 20th century ‘ninja’ authors.10 Supposedly, according to this text, one might use female servants or ladies-in-waiting to help male shinobi enter a restricted area by smuggling him into the ladies’ quarters concealed in a clothes chest. OK, fine, but - is there any evidence anyone actually did this? And the answer, simply, is no - as far as we can tell, there is no evidence that anything resembling this ever happened. What this means is that in most cases we have no way of determining whether what’s presented is real-world shinobi knowledge, some garbled second-hand account, or just a bunch of crap the authors made up in the pub one night. (Personally, I like to mentally preface almost every shinobi technique presented in the ‘ninja manuals’ with the words, “Dude, wouldn’t it be cool if…”)

The image of a bunch of dudes in a bar making up ‘secret ninja knowledge’ brings me neatly to my third point…

Point #3: Some of the Stuff in the ‘Ninja Manuals’ is Almost Certainly Bullshit

Quite a bit of what’s included in the ‘ninja manuals’ is obviously nonsense to any moderately critical reader. As one example, the Bansen shūkai contains a section about how you can tell the time of day by looking at a cat’s eyes.11 Here I can do no better than quote John Man’s dismissal in his kind-of-skeptical-kind-of-not book about ‘ninja:’

First, of course a cat’s eyes dilate and contract with the changing light. All eyes do. You might as well tell the time by staring into a mirror. Second, do you really need a cat to tell you the time of day? Third, the amount of light and thus the size of a cat’s pupil depends on not only on the time of day but also the season and the weather. And once you spot a cat, how on earth do you get close enough to get a good look at its eyes? The more you think about it, the sillier it gets.12

As a cat owner myself, I might also note that cats’ pupils contract and dilate according to their emotional state as well, so a shinobi who startled a cat might well get a completely wrong feline reading. Or something like that - the whole thing is not really worth taking seriously.

The second example would be the notorious mizu-gumo device for supposedly ‘walking on water,’ which the US TV show Mythbusters experimented with a few years ago and which I don’t want to go into here - we’ll discuss it in a later post.13

Don’t Believe Everything You Read

Based on the above three points, I would urge extreme caution regarding any piece of information from any alleged ‘ninja manual.’ While I understand the commercial incentives at work to present their contents as AUTHENTIC NINJA WISDOM, I can’t help but think that this framing is badly misleading to popular audiences.

Now, to be clear, I am not saying that the manuals themselves are inauthentic or ‘fake’ - there is no evidence to support that position, as far as I can see. What I’m saying is that we should understand these materials as representing what a bunch of dudes decades later thought the shinobi MIGHT have done, not as a definitive and completely reliable guide to what they actually did. I don’t think the latter position can be supported by a serious critical historian, though it does appear to be the default for most popular authors and online journalists. As they say, it’s hard to get someone to understand something when his income and profile depend on him not understanding it.

So this is where we’ve wound up with the whole ‘did ninja wear black?’ thing. We’ve seen that a lot of English-speaking scholars have badly misread a lot of Edo-period art, identifying ‘ninja’ in Edo period prints that don’t contain them at all. We’ve then shown that the ‘ninja wore hoods but didn’t wear black’ idea isn’t based on any very solid historical evidence and that it wasn’t there in pre-modern Japan. Instead, it seems to have had a fairly precise point of emergence, from 1909 onward, and it came from the pen of one or two specific writers with very unorthodox views of Japanese history.

I should note, by the way, that Gingetsu’s writings don’t seem to have been very influential on the broader Japanese public; it wouldn’t be until the late 1950s and early 1960s that the ideas he was putting out got much traction in Japan itself, by which point Gingetsu himself had gone to the great ninjutsusha training hall in the sky. But I think it’s worth noting that Gingetsu wasn’t just making shit up; he actually did have a pre-modern textual source for his claims, albeit one that was not especially reliable and whose claims can’t be corroborated from other sources. In a certain sense, Gingetsu’s work contains a lot of ‘ninja’ history in microcosm. It’s comparatively rare, I have found, for ‘ninja’ claims to be simply made up out of whole cloth; rather, there generally is at least some textual or historical basis for them, though usually the ‘ninja’ claims involve twisting, misreading, or otherwise torturing the historical sources in various imaginative ways.

So we’re almost done with the ‘black hoods’ thing for now, I think, though I have a few more thoughts about Gingetsu, the ‘ninja manuals’ and ‘ninja secrets’ in general for the next post or two. Once we’re done with that, we’ll go on late next week to take a look at the well-known Uesugi Kenshin ‘toilet ninja’ myth, and see if we can, uh, get to the bottom of it.

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu no gokui, p. 62. Translated slightly differently by Shahan on pp. 68-70 of his The Essense [sic] of Ninjutsu.

Full disclosure time - my ability to read handwritten Japanese texts is pretty shaky (though not non-existent - I do have at least some training in doing it). So I’ve used an amazing piece of software called Mio that provides basically OCR reading of these texts. Since Mio isn’t always 100% accurate, I’ve also followed Mie University Ninja Research Center scholar Katsuya Yoshimaru’s rendering as given here.

This is my translation, based on the original. You can, if you prefer, read a different translation of the same passage by Minami Yoshie in Minami and Cummins, True Path of the Ninja: The Definitive Translation of the Shoninki (Tuttle, 2017), p. 52-53.

Turnbull writes in his 2017 Unmasking the Myth that Gingetsu “made little use of the Shōninki” (p. 126). I suppose we could debate what “little use” means, but since Gingetsu is basing multiple sections of multiple books on the Shōninki, that doesn’t really strike me as “little use.”

I think the problem may well be that Turnbull used Shahan’s translation rather than looking at the original Japanese text; at least, there’s no original version of Ninjutsu no gokui cited in Unmasking the Myth’s notes and bibliography. Shahan’s translation romanizes Shōniki as “Seininki,” so Turnbull may not have realized that the two were the same text. This would have been obvious if he had checked the original, where it’s there in kanji in plain sight.

This might also explain why Turnbull says of Gingetsu’s 1917 work that Shōninki is among “his likely sources” (p. 126 again, emphasis mine). There’s no “likely” about it - Gingetsu explicitly mentions Shōninki several times (see e.g. Gingetsu 1917 pp. 64-68).

I mean, I get it - sometimes it can be hard to get hold of an original Japanese text, in which case it’s perhaps excusable to use a translation. But the Japanese text of Ninjutsu no gokui is available online for free through the NDL, and according to the bibliographic data the text was digitized in 2010, so it would have been available when Turnbull was writing his book.

Turnbull’s Unmasking the Myth is, as I’ve said, a lot better than his earlier work, but he still hasn’t quite shaken the tendency toward sloppiness that dogged his earlier works.

Gingetsu, p. 69; Shahan, p. 73. Japanese: Suhō-zome 蘇芳染め.

I say “since the 1970s” because several notable ‘ninja’ historians during the 1960s - including, incredibly, Okuse Heishichirō - were openly skeptical about the reliability of military manuals such as the ones we discuss below. I’ll say more about their views in the next post.

Thanks to Eric Schluessel for bringing this to my attention. He also pointed out the hilarious phrasing “thirst balls” as well.

Bansen (or possibly Mansen, we don’t really know) shūkai 万川集海. It means literally “ten thousand rivers converge to form an ocean” and is probably a reference to knowledge of shinobi techniques from various sources being collected into one whole. It’s also available in translation by Minami Yoshie (with assist from Anthony Cummins) as The Book of Ninja: The Bansenshukai - Japan's Premier Ninja Manual (Watkins Publishing, 2017).

Turnbull, Unmasking the Myth, pp. 106-107.

Japanese: Kunoichi くノ一. The original text of one version of BSSK is viewable in, of all places, the website of the Japanese cabinet office. If you can read Japanese, the kunoichi section is vol. 8 p. 14-15 (equivalent - unpaginated). Minami’s translation can be found in The Book of Ninja, p. 107.

I am definitely lining up a series of posts on kunoichi, so stay tuned.

John Man, Ninja: 1000 Years of the Shadow Warrior: A New History (W.M. Morrow, 2013), p. 128.

I think the idea that it was worn as a shoe comes from Fujita Seiko, who - despite being a 14th generation NINJA GRANDMASTER - obviously didn’t know jack about physics. And yes, I am aware that ‘ninja’ historians have subsequently argued that it’s actually a flotation device you sit on in the middle. I’m skeptical of that too - a lot of the retrofitting of the mizu-gumo seems to involve stuff that’s not actually in the original text. It seems pretty clear that there’s a concerted effort (a) to find some way in which the device could work, so as to shore up the BSSK’s credibility, and (b) not to consider the possibility that the whole thing might just be complete bullshit to begin with.