In our previous post we looked at some examples of the kusari-gama chain-sickle being depicted in famous (though probably fictional) duels between early Edo-period martial arts masters. Entertaining though they are, fictional and semi-fictional accounts are not the best source for learning about how the kusari-gama might actually have been used, so as promised, let’s take a look at some accounts of the weapon from less obviously literary sources.

To give the conclusion in advance, I can’t find any mention of an association between shinobi and the kusari-gama in any source before about 1960 or so. No account of the weapon I have found suggests that it was regularly used by shinobi or that it was associated with them in popular or literary culture. This isn’t terribly surprising, since most of the available historical evidence suggests that shinobi was a temporary role within warfare rather than a clearly defined group with specific practices. Instead, what I’ve found is that there seems to have been a reasonably strong connection between the kusari-gama and a completely different societal group, namely women.

Kusari-gama as Standard Martial Arts Weapon

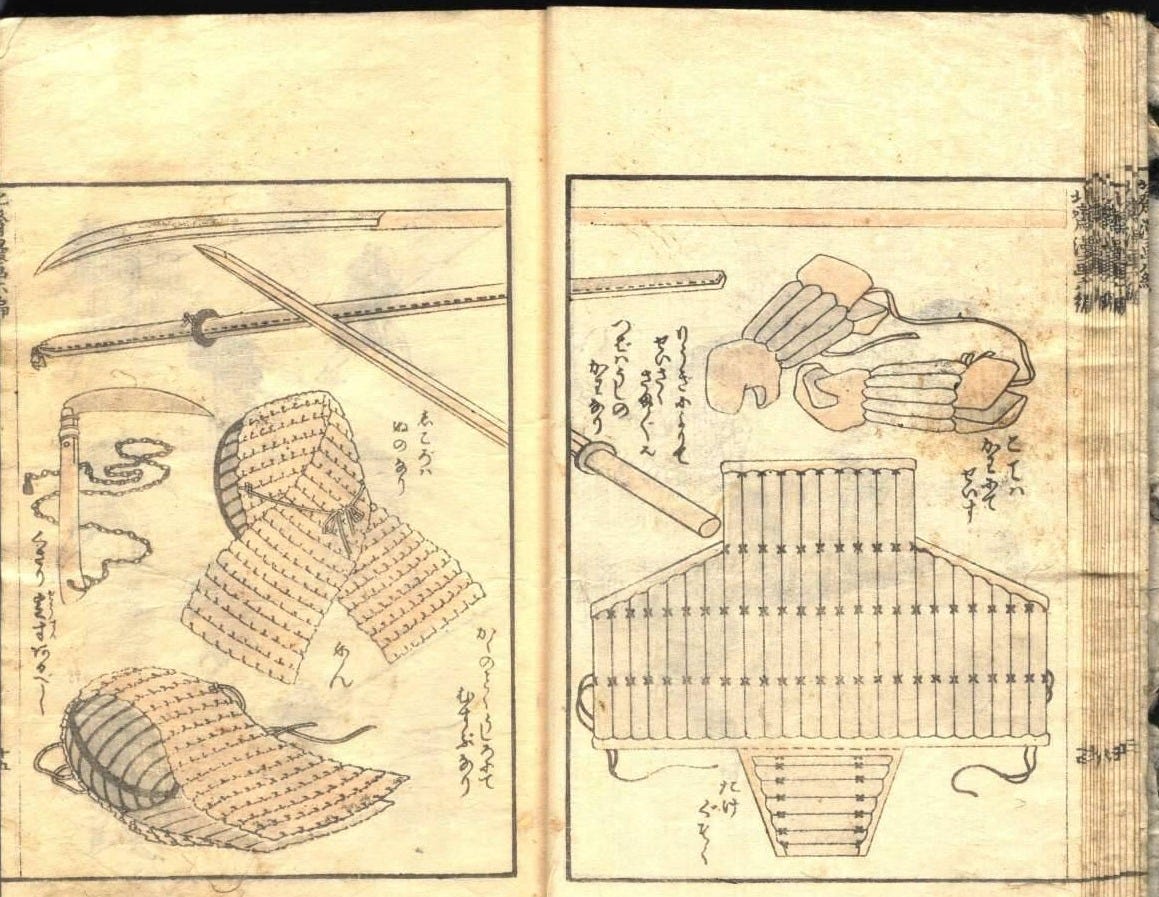

To back up a bit, it seems that by the 19th century the kusari-gama had become a pretty common choice in Japanese weapon-based martial arts. It pops up as part of a range of weapons in which many people trained, including sword, spear, and naginata glaive, and so matchups between kusari-gama user and swordsman seem to have been a standard part of sparring in weapon-based martial arts. The famous artist Katsushika Hokusai’s Random Drawings by Hokusai (Hokusai manga, 1819), for instance, includes a kusari-gama on the left-hand side alongside drawings of the sword, naginata glaive, and a set of armor resembling what is used in modern kendō:

In an example probably falling a little earlier in the Edo period, the late 19th and early 20th century Japanese haiku poet Masaoka Shiki - probably the greatest haiku poet of the modern era - records that his great-grandfather Masaoka Tsunetake had been a teacher of the quarterstaff and the kusarigama.1 I know Shiki’s life story very well - I wrote a book on him earlier in my career - but had missed that particular detail, so I got a kick out of turning up that one.

Anyway, moving a little later into the 19th century, it seems that Westerners visiting Japan during the early and mid-Meiji periods also noticed the kusari-gama as a dueling weapon at various martial arts displays. Here’s an account of one such duel in April 1873:

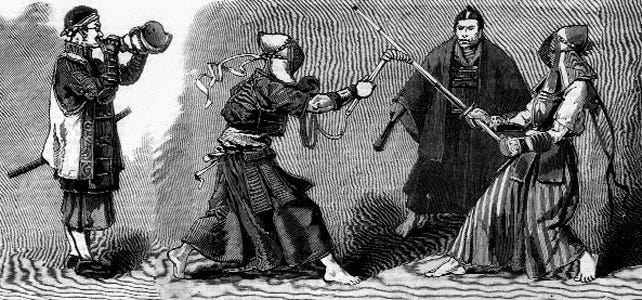

A new weapon is now introduced, called the kusari-gama, or "chain-sickle." This consists of a short stick, in the end of which, and at right angles to it, is fastened a small blade some four or five inches long, which is carefully wrapped round with cloth to prevent accidents. This is the shape of the ordinary grass-sickle used by the Japanese peasantry. To the top of the stick is also attached a three-feet rope, with a leathern ball at the end of it, which is supposed to represent a chain connected with a ball of iron. The fencer who bears this also carries in his belt a short dirk. The other is armed with the ordinary long sword, and comes on valiantly to the attack; but his opponent skilfully whirls the ball around him, trying to entangle the sword-blade, and then locks in to catch his antagonist’s helmet with the hook in the of the sickle and drag him down. Once he succeeds, but has to spring back again to avoid a heavy blow from the sword, and so for that time they are quits. Finally, however, by a dexterous turn of the wrist, he brings down the ball full on the other's head, and so wins the first hit. In the next round, the swordsman has the best of it, and the combat eventually ends in a draw.2

Note that for sparring purposes it seems that a rope was preferred rather than a metal chain, presumably to reduce the risk of injury. The British painter Charles Edwin Fripp appears to have observed a similar matchup during his time in Japan, judging by a painting from 1882. The guy on the left, in case you’re wondering, is blowing a shell as a signal to begin and end the bout.

The Feminine Touch

The kusari-gama wielders in the accounts above are all men, but there’s also evidence to suggest that the weapon was considered suitable for women to train in and use as well. We already noted its role in the famous (though probably fictional) revenge killing by the sisters Miyagino and Shinobu, but it seems that that was far from the only time that a woman picked up the weapon. At the bottom of the 1888 drawing of the kusari-gama from the French journal I showed you last time, for instance, we read the following:

Even if you don’t know any French, you can probably work out what “instrument de combat pour les femmes” means. The connection to women seems to have been repeated frequently in subsequent English-language discussions of the weapon; George Cameron Stone’s amazingly obsessive book A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times, Together with Some Closely Related Subjects (1934), for instance, concludes its discussion of the kusari-gama by noting that “[i]t is also said to have been used by women.”3 One of Donn Draeger’s early articles on martial arts in 1961 likewise acknowledges that the kusari-gama was “used by both male and female exponents” and features photos of a female kusari-gama expert named Ono Eiko:4

It’s completely possible for Western observers to get things like this wrong, of course, but in this case there’s corroborating from Japanese sources that women did indeed train in the kusari-gama more than in other weapons. The kusari-gama seems to have been commonly taught alongside the naginata glaive, which readers with a background in martial arts will probably know was (and is) favored in women’s martial arts as well. We can see women wielding both kusari-gama and naginata in the 1815 splash illustration for this post (back up top), and it appears that things didn’t change much over the subsequent century or so. In a 1937 record of martial arts instructors in Japan, for instance, two of the three listed teachers of the kusari-gama are women.5 This is consistent with a 1969 article in Black Belt magazine on the kusarigama, which interviewed a woman named Kobayashi Seiko:

Kobayashi first studied kusarigama when she was 12 years old. Later, she also practiced naginata. In 1929 she became the head mistress of the school and was granted the official scroll and old records of the ryu [= style]. In 1934 she taught naginata at Japan Girl’s School in Koshikawa [sic] (now Bunkyo Ward), but the school was completely destroyed by fire during the war.6

So it would appear that, while the kusari-gama was not exclusively a woman’s weapon, enough women trained in its use that it definitely came to be associated with women, to the extent that foreign observers were moved to remark upon that fact fairly consistently. The evidence I’ve presented above, then, makes it clear that there was a documentable association between women and the kusari-gama; we can show not only that women used and trained in that weapon over and above other weapons available at the time, but also that when outside observers came across the kusari-gama, it was made known to them that it was associated with women.

What I have presented above is, to be blunt, how it’s supposed to be done; I’ve gathered a range of sources from different historical and linguistic contexts spanning about 150 years that, taken together, make a pretty compelling case for an association between women and the kusari-gama. I find, though, that I can make no similar case for an association between shinobi and the kusari-gama; mentions of shinobi in discussions of the weapon seem to be conspicuous by their absence. If the kusari-gama was indeed a shinobi weapon and known to be so, you would expect someone somewhere to have mentioned that at some point, but apparently not.

What we’re finding is that the kusari-gama, for all its exotic appearance, was actually pretty standard in Japanese martial arts as a whole. It was a widely known weapon that almost anyone could train in and which was particularly favored by women, but which, in these pre-1960s sources, appears to have no obviously discernible connection either to the fictional ‘ninja’ or to the historical shinobi.

That, of course, raises an obvious question, which is how the putative connection between the ‘ninja’ and the kusari-gama got started in the first place. But we’re running out of space for today’s instalment, so that’s what we’ll look at in the next post.

Masaoka Shiki 正岡子規 (1867-1902): “My great-grandfather was a different man from my great-great grandfather; he taught the use of the quarterstaff and the kusari-gama, or so I have heard. I have also heard that he liked a drink.” (Japanese: 曾祖父は玄祖父と違ひ棒をつかひ、くさり鎌をつかふことを教へ給ひしと。又酒を好んで飲み給ひしとか聞きぬ。) In Shiki zenshū [Complete Works of Masaoka Shiki] (Kodansha, 1975), 10:148.

Anon, “A Fencing Tournament in Yedo” The Spectator October 31st 1874, pp. 1359-1360.

George Cameron Stone, A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times, Together with Some Closely Related Subjects (first pub. 1934, this ed. J. Brussel, 1961), pp. 403-404.

Interestingly, although the article does discuss ‘ninja,’ Draeger does not connect them at all to the kusari-gama. Draeger seems instead to understand the kusari-gama as simply one of several well-known weapons used across Japanese martial arts in general.

A Register of Masters, Teachers, and Trainers in the Martial Arts (Budō hanshi kyōshi renshi meikan 武道範士教士錬士名鑑 ) (Butokukai, 1937), p. 296.

[Sic] because “Koshikawa” should be “Koishikawa.” Lloyd Williamsen, “Kusarigama: Tool for Survival” in Black Belt December 1969, p. 21. I know Black Belt is not generally a great source, but the martial arts school mentioned still exists and confirms the basic details on its website.

Will there be a take (or a comment) on the famous Hokusai’s ‘ninja’ drawing in the “Hokusai manga”? Can we deduce anything from the fact that it appears on the same page as ‘jūjutsu grapplings’?

As an aside, pleased to see a copy of Idly Scribbling Rhymers is available in my university library. Will check it out.