The Chain-sickle (Kusari-gama): A Cultural History

Tracing the story of the (alleged) 'ninja' weapon

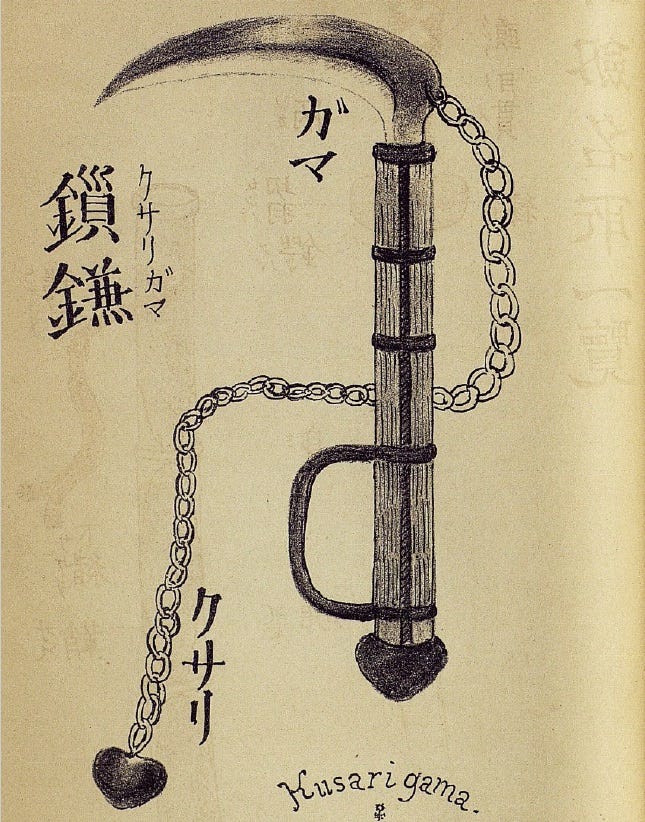

I came across the above image in 2019 on a week-long research trip to Paris. (Yes, I know, I have an arduous and demanding job).1 It’s from Le Lotus, a French academic journal focusing on Asia published during the 1870s and 1880s. It depicts, as you can see, a weapon known as a kusari-gama, or chain-sickle. The kusari-gama is a distinctive Japanese weapon and one that many people believe was strongly associated with the historical shinobi. You can find this claim being advanced by the usual suspects, like Donn Draeger:

One composite weapon that was always a part of the ninja’s paraphernalia was the kusarigama. A wooden handle to which a sickle blade was hafted at right angles, and a weighted chain made up the design of this unusually effective instrument….as a tool or weapon, it was respected by all warriors who had faced it in combat. The ninja used this weapon to slash and stab at his enemy, parrying or blocking the enemy’s weapon, and perhaps ensnaring the enemy or his weapon to render his victim helpless.2

…but it also pops up in works by scholars with more legit academic credentials, like William Deal:

The crescent-shaped sickle (kusarigama) was a weapon especially associated with ninja infiltrators….By swinging the chain, the warrior generated significant velocity to disrupt use of an opponent’s weapon, cause injury, or entangle the opponent with the lethal sickle-like blade.3

In this and the next post or two I’d like to take a look at what the available historical and cultural evidence can tell us about the kusari-gama. I’d like to get a sense of the history of the weapon, how and by whom it might have been used, and most of all, whether there’s any evidence to support the idea that the weapon was used by or associated with the historical shinobi.

It’s Not Completely Made Up

Given the generally fantastical nature of ‘ninja’ history, the first question to ask should probably be: is the kusari-gama just made-up bullshit?

The answer there is a pretty clear ‘no’: there’s a lot of evidence that the kusari-gama predates the emergence of the idea of ‘ninja’ in the late 1950s and early 1960s by hundreds of years. It appears to have been a fairly well-known weapon in Japanese martial arts from the Edo period (1600-1867) through the first half of the 20th century.

It’s not entirely clear from the sources I’ve reviewed when the weapon was first invented and/or used, but the evidence suggests it probably appeared in the mid-to-late 1500s. This auction catalogue from 1908 mentions a kusari-gama dated to 1500 (though that could well be inaccurate), while a catalogue from an exhibition of Japanese culture held in London in 1910 includes a kusari-gama as one of the exhibits and suggests that the weapon came into use around 1570. A 1969 interview in Black Belt magazine with a Japanese kusari-gama instructor suggests that his school was founded around 1599, though another school apparently traces its lineage to a monk active during the late 1300s. Both Black Belt magazine itself and claims about martial arts lineages should be taken with a considerable helping of salt, but overall the evidence seems to suggest that the kusari-gama probably emerged in the last few decades of the Warring States period (1467-1600).

Miyamoto Musashi Meets the Kusari-gama

The notion that the kusari-gama emerged in the late 16th century is consistent with further evidence that suggests it had been reasonably widely adopted by the early Edo period. The legendary swordsman Miyamoto Musashi, for instance, is reputed to have fought a duel against at least one man using a kusari-gama, in which Musashi emerged victorious.

Miyamoto Musashi, if you’re not familiar, was an incredibly famous swordsman active in the late Warring States and early Edo period. I would imagine just about everyone with a passing interest in Japanese history has heard of him, so I should probably make something clear before we go any further: You have to be extremely careful when dealing with any purported event in Musashi’s life. Ever since his Book of Five Elements (Gorin no sho) blew up in the 1980s as a self-help book for middle management types, there’s been a ton of pop stuff written about him in English, and much of it is total crap. The basic problem is eerily similar to the ‘ninja’ thing, in that a lot of the authors purporting to write straight history about Musashi appear unaware that they are recounting events from later fiction, particularly semi- and totally fictional elements from the writer Yoshikawa Eiji’s historical novel Musashi (pub. 1935-39).

With that caveat in mind, here’s the duel. There’s no precise date given, but from context it appears to have taken place around 1604 in Iga Province, against a man named Shishido:

While Musashi was in Iga Province, there was a man named Shishido something-or-other who was skilled with the kusari-gama. Going forth into the fields, Musashi fought a duel with him. Shishido began swinging his sickle around, at which Musashi drew his dagger and threw it into Shishido’s chest. Shishido crumpled to the ground immediately, and Musashi came forward to deliver the coup de grace.4

This is kind of a lower-tech version of the famous “gun vs. sword” scene from Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark. Faced with an enemy whirling a melee weapon around, Musashi just took him out from range, the kusari-gama being no match for an opponent who was willing to cheat.5 Iga Province is, I hardly need to add, famous as the supposed heartland of the historical shinobi, but I would hope it’s obvious that you can’t simply claim everyone from Iga Province as a shinobi on general principle.

Get Out of That One! What? Oh.

There’s also an interesting (though probably fictional) account of a duel between a kusari-gama master named Yamada Shinryūken and another famous swordsman, Araki Mataemon, which supposedly took place around 1634.6 The source appears to be a tale told by kōdan oral storytellers, who are not remotely reliable historical sources but were very popular nonetheless.

Once the duel begins, Yamada successfully tangles Araki’s sword with his chain, but Araki simply stabs Yamada with his back-up blade. Here’s how the story appears in an English-language source in 1929:

For a while the two stood motionless staring at each other. Then Yamada finding a chance, threw his lead weight at Araki. It was so quick that Araki could not dodge, and had to parry it with the sword. But alas! The sword was coiled about by the chain. He was placed in a very precarious position. But he escaped it by a lightning trick, which could be hoped from none but such a master as he. With all his energy he cried “eh!”, and cast the chain-coiled sword at the opponent, and in next moment he sprang at him and stabbed the short sword in his breast. With a scream Yamada fell backward, and in an instant Araki’s short sword went to give the coup-de grace, when Yamada stopped him and asked him who he really was. Araki gave his real name. Hearing it, Yamada cried: “I'm quite satisfied at dying at the hand of such a master swordsman as you.”7

Kusari-gama masters going 0-for-2 here, by the looks of it. We see the chain part of the kusari-gama used here to disable an opponent’s weapon, as we might expect, but the anecdote also suggests that the savvy warrior knew a way around that - draw another blade and stab the bastard with that one instead.

Fighting Like a Girl

A more successful use of the kusari-gama appears in the tale of Miyagino and Shinobu, a story of two sisters who secretly trained in the martial arts in order to avenge the murder of their father by a samurai named Shiga Danshichi some time around 1630. Challenging Danshichi to a duel, the sisters overcome him by dint of their skill in the naginata glaive, kusari-gama, and shuriken throwing-knives.

The villain Danshichi is defeated when Miyagino entangles his arm with the kusari-gama and cuts off his arms with the sickle-blade, and Shinobu then finishes him off. You can read an early English-language account of the duel from 1877 here, but this is the main part:

A desperate fight ensued, and at last Miyagino succeeded in planting shuriken in both eyes of her opponent. Blinded by this, Danshishi [sic] struck wildly in every direction with his sword, until Miyagino entangled his right arm with the chain attached to her sickle, and then with one blow cut off both his arms. Calling Shinobu to her she directed her sister to sever the head of their foe from his body, which was at once done, to the admiration of all present. Thus was the girls’ long sought for revenge accomplished.8

So there you have it.

Now, the thing is that although all of the above accounts suggest that the kusari-gama was a widely-known weapon across the Edo period, all of them are pretty dubious from a factual point of view.9 They can perhaps tell us something about the kusari-gama as it was known and depicted in Edo-period fiction and pop culture, but it’d be unwise to rely on these accounts as evidence for how the weapon was actually used in real life - or even that it was used in the first place. Ideally, we’d want to look at a source or two that’s less obviously in the literary-fictional mode. Happily, there are indeed a few of these, so those are what we’ll consider in the next post.

Believe it or not I did legitimately need to go to Paris and got a lot of useful research material out of the trip. I picked up a ton of info about French Japanology in the late 19th century, and got a major publication out of it in one of the most prestigious journals in the field, thus: Robert Tuck, “Nihon gaishi Goes Global: A Translation History of a Nineteenth Century Blockbuster” Monumenta Nipponica Vol. 76 No 1 (Winter 2021), pp. 69-115 (paywalled, alas).

Donn F. Draeger, Ninjutsu: The Art of Invisibility (Tuttle, 1989), pp. 70-71.

William E. Deal, Handbook to Life in Medieval and Early Modern Japan (Oxford University Press, 2007), p. 166.

Miyamoto Musashi (author), Mitsuhashi Ken’ichirō (ed.) Kendō hitsuyō: tsuketari Musashi jitsuden Niten-ki [The Essentials of the Way of Swordsmanship: Including Niten-ki, a True Biography of Musashi] (Butokushi, 1909), p. 4 (Niten-ki section). Japanese text: 一武蔵伊賀国ニテ完戸何某ト云者鎖鎌ノ上手也野外ニ出テ勝負ス、完戸鎌ヲ振出スヲ武蔵短刀ヲ抜キ完戸ガ胸ヲ打貫キ立所ニ斃レシヲ進デ討果ス。The episode isn’t precisely dated, but the preceding passages suggest the date as around the ninth year of Keichō (1604). Note, as below, that Niten-ki is not by Musashi himself.

The caveat about fact and fiction with Musashi applies doubly here, because the text this is drawn from, Niten-ki (‘An Account of Niten ichi-ryū Swordsmanship’) was written in 1776, around 130 years after Musashi’s death, so it has to be treated with considerable skepticism. If you go reading through accounts of Musashi’s duels, you’re likely to find a lot of writers naming the unfortunate kusari-gama master as Shishido Baiken. But the name “Baiken” isn’t in the 1776 account, as you can see in both the English and the Japanese; it’s an invention of the 1930s novelist Yoshikawa Eiji. So the moment you see any writer calling Musashi’s opponent “Baiken,” you’re dealing with someone who’s unsure of the boundary between modern fiction and historical sources.

Yamada Shinryūken 山田真竜軒 (possibly 1581-1634); Araki Mataemon 荒木又右衛門 (1599-1638). It occurs to me to wonder if Yamada Shinryūken is the guy Kacem Zoughari meant to refer to here when he screwed up his caption. Speaking of screwing up, Turnbull mentions Yamada in his 2008 book The Samurai Swordsman but gets his name wrong (as Shinryūkan), and wouldn’t you know it, now almost EVERY mention of Yamada in English also gets his name wrong in the exact same way. I swear to God, it’s going to take decades to clean up the mess that Turnbull has left behind.

Anon, “Master Swordsmen in Japan” The Japan Magazine October 1929, pp. 489-90. The source for this particular version of the story appears to be a kōdan performance by the famous raconteur Tamada Gyokushūsai 玉田玉秀斎 (1856-1919), who, funnily enough, also played a big part in the Sarutobi Sasuke stories. You can read a Japanese version of the same story from 1910 here (cell #173 in the viewer, 332-333 in the pagination)

Anon, “Some Other Chapters of Japanese History” Japan Weekly Mail November 3rd, 1877. Note that shuriken here are throwing-knives, not the star-shaped ‘ninja’ weapon. It’s possible, now that I think of it, that this is where the idea that ‘ninja’ used shuriken not to kill but to distract or blind their opponents might have come from.

As Marcia Yonemoto points out, Miyagino and Shinobu’s story is often portrayed as something that really happened, but there’s strong reason to doubt its factual status, and at least one Japanese scholar has termed it “a complete lie.” See Yonemoto, The Problem of Women in Early Modern Japan (UC Berkeley Press, 2016), p. 232.

Great read. Looking forward to the next article.

Another great post. I checked the sources in Deal’s Handbook and, やっぱり, the usual suspects…