Important if True

'History' is the default setting in ninja writing, but it probably shouldn't be

Last time around we looked at a short article on kunoichi by a French scholar named Marc Kober. One of the things I found fascinating about the piece is that although the kunoichi is almost entirely a fictional phenomenon, Kober begins and ends the piece by gesturing towards what he believes to be the historical reality underlying it. He discusses the alleged Takeda kunoichi spymaster Mochizuki Chiyome in considerable detail, for instance, and closes by suggesting - perhaps with tongue in cheek - that the loony magical powers of the modern movie kunoichi are an extrapolation of their real role as seduction agents.

It’s odd that Kober feels the need to bookend his piece by insisting on the historicity of the kunoichi, particularly given that the journal in which he’s publishing, Supérieur Inconnu, was founded by a group of Surrealists - not known for their rigid adherence to empirical reality. But this is something that almost everyone who writes on the topic of ‘ninja,’ both popular and academic, tends to do. The most recent academic publication on the topic before my article this Spring was Serebriakova and Orbach’s “Irregular Warfare in Late Medieval Japan: Toward an Historical Understanding of the ‘Ninja,’” which appeared in 2020 in the Journal of Military History. The abstract to their article is as follows:

The Japanese ninja are known in the west mainly by the romantic image of the secret agent, or assassin, endowed with superhuman powers. Yet there is a lack of serious scholarship on the actual warriors who became the subject of the myth. This paper seeks to use the full extent of primary sources from the period to offer a blueprint for a historical, rather than mythical understanding of the ninja. They did not belong to a unified class, but were instead a hodgepodge of heterogeneous groups, united only by their skills in irregular warfare. They became “ninja” only retrospectively, as a result of the historical imagination of later generations.1

Lest I be misunderstood here, “Irregular Warfare” is a perfectly good article in terms of what it’s trying to do. But you could easily get the impression from this abstract that the bulk of ‘ninja’ writing before 2020 had been about the “romantic image,” the “myth,” and the “historical imagination” to which the authors refer. In fact this is not the case; the focus of ‘ninja’ writing, particularly in English, is overwhelmingly on trying to piece together the historical facts that may or may not underpin the ‘ninja.’

I think this tendency to approach ‘ninja’ as first and foremost an historical question - that is, one to be resolved through conventional historiographical analysis, focusing on primary sources, documents, and ‘what really happened’ - has been a huge problem for the field. I’m not just talking about the horrifically embarrassing tendency to mistake fictional characters for historical ones; that’s a symptom of the deeper problem. The deeper problem is that the history-first approach very often either ignores or dismisses a rich and creative seam of literary discourse on ‘ninja,’ and by doing so it fails on a fairly fundamental level to grasp what the ‘ninja’ phenomenon is. As I pointed out a few posts ago, if you look at the ‘ninja’ phenomenon in the aggregate, in Japan at least, the total output of fiction writers like Yamada Fūtarō absolutely dwarfs the output of the supposedly historical guys. If you put it in terms of a percentage ratio, it’s probably like 85-15 in terms of page count between the literary fiction and the supposed history. Under the circumstances, wouldn’t it make more sense to start with the 85%, or at least take it seriously?

The Ring of Truth

Why should this be the case, though? Why has the dominant approach to studying the ‘ninja’ been primarily historical, or at least believed itself to be?

I think it’s pretty simple: history is true. It’s about things that really happened, so it has cultural prestige. Historical fiction, by and large, isn’t and doesn’t. This perception is only strengthened by the sense that historical novels are very often low-quality, mass-produced crap. Even in English, there’s a truly astonishing number of historical novels about Japan out there, most of which you’ve probably never heard of. And - speaking to my academic readers here - how many of you roll your eyes when you come across Memoirs of a Geisha or Shogun when you’re searching through Google Books? C’mon, be honest here.

The cultural role of HISTORIAN, in similar vein, is more intellectually prestigious than that of historical novelist. A few months ago I pointed out that Thomas Lockley had been doing some stuff he really shouldn’t have with his supposedly historical book African Samurai, including apparently inventing episodes in Yasuke’s life out of whole cloth. When the impending release of the video game Assassin’s Creed: Shadows caused the Yasuke thing to blow up last summer, a few people, myself among them, noted that Lockley could easily have avoided all of the vitriol that came his way if he had given African Samurai the sub-title “A Novel” rather than insisting that it was “The True Story of Yasuke.” Lockley’s co-author Geoffrey Girard literally is a novelist, so it’s not like the idea of fiction was completely unfamiliar. So why the insistence on history? Simple - the hypothetical Yasuke: A Novel would never have garnered anything close to the same attention, because historical novels (a) aren’t true, and (b) are ten a penny, so hardly anybody takes them seriously.

The Order of Things

I think it’s also the case that quite often, as literary scholar Brian Hamnett points out in his study of the historical novel in 19th century Europe, academic history doesn’t always know what to do with historical fiction.2 If you’re in Japan Studies, there’s a good chance you’ve gotten the dreaded question “Is Shogun accurate?” over the last year or so. I know I have, and I’m genuinely unsure how to answer that question. Strictly speaking none of it is - none of the named characters existed! - but clearly that doesn’t diminish the general sense that you can learn something about real Japanese history by watching it. I just taught a whole class on how to think about anime with historical settings at ASU this past Spring semester, by the way, so this topic has been very much on my mind. (Happy to share the syllabus if anyone wants to copy the class, btw.)

Hamnett points out that the possibility of confusing historical fiction with fact, something that happens all the time in ‘ninja’ history, is not a new problem; it had been noted as a possible danger as early as 1850 in a study by Italian critic named Alessandro Manzoni, just as the genre of the historical novel was rising to broad popularity in Europe.3 More recent scholarship on the topic, such as work by the Canadian scholar Linda Hutcheon, has called attention to the uncertain boundary between fiction and history as something interesting and even postmodern (to use a thrice-damned term). Hutcheon notes that works by later 20th century authors such as Salman Rushdie sometimes call attention to their fictional status as a deliberate device in their stories, and so she suggests that this sort of thing requires a new term to describe it, which is to be found in the title of her essay, “Historiographic Metafiction.”4

But here’s the thing. In all of the above, there’s an unspoken assumption about the priority relationship between history and historical fiction, namely that the historical events happen first and are then depicted in literary form. In that sense, historical fiction is always in some sense subordinate to proper history, a mere copy or reflection of the truth. This is an assumption so obvious that it seems almost banal to mention it, but - and this is the key point - it does not apply for much of ninja history. Representing fiction as fact is simply not supposed to happen - so not supposed to happen, in fact, that we don’t really have a model we can use to wrap our head around it. It’s the diametric opposite of Hutcheon’s “historiographic metafiction”; instead of deliberately calling attention to its status as fiction, ‘ninja’ history can often be found insisting that fictional tropes are historical facts.5 This, I think, explains a lot about the howling errors made by writers like Andrew Adams back in the day Films like Shinobi no mono must be based on real events, because that’s how historical films work. So you’re basically OK in using them as sources for historical claims, because there’s got to be some factual basis in there somewhere, right?

The Truth is Out There

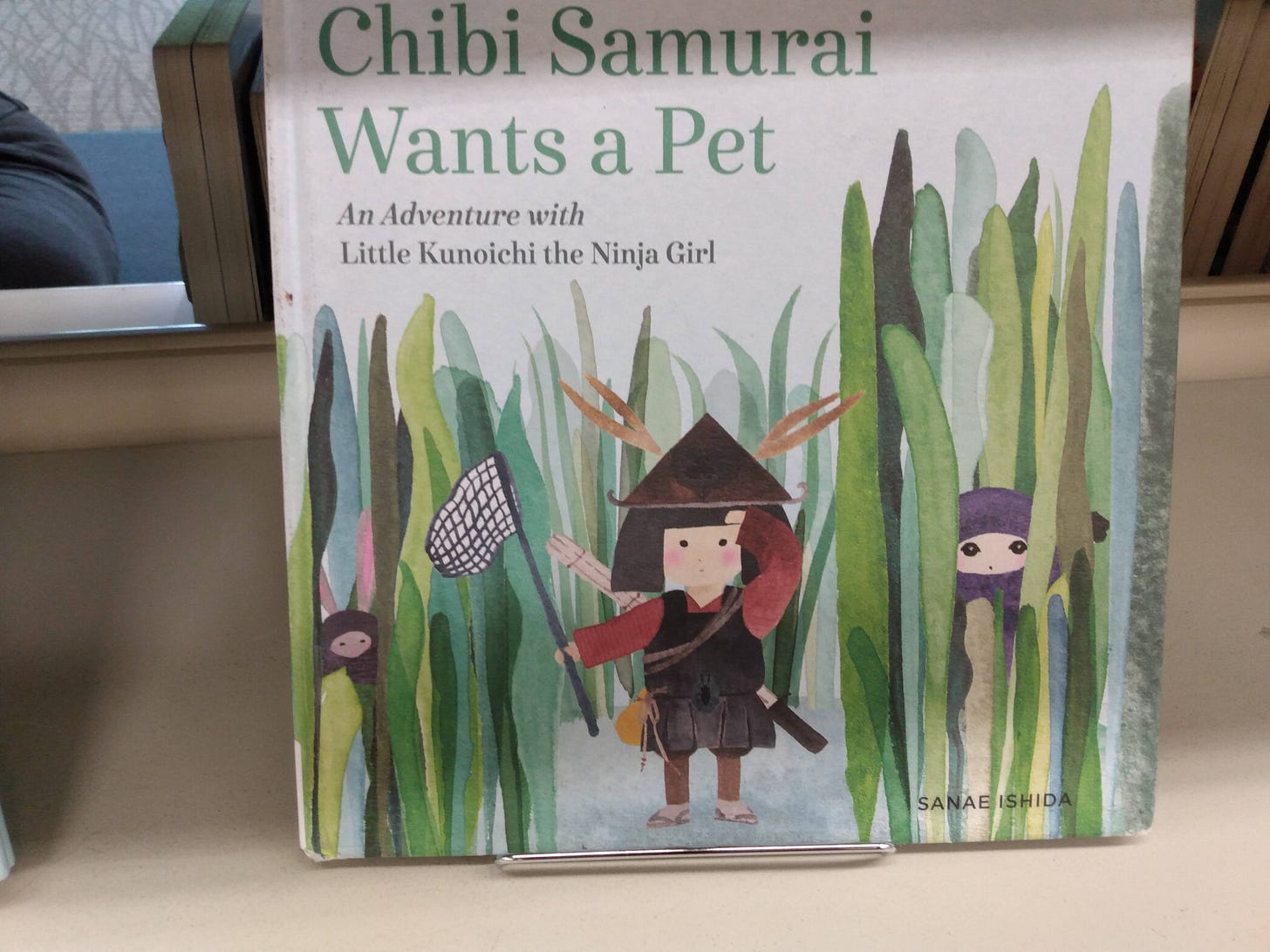

It’s striking, in fact, how dismissive a lot of the OG ‘ninja’ writers were of the literary realm. Draeger talks of writers with “overly active and imaginative minds” and of the “superstitious minds” of the common people; Turnbull talks of “myth and exaggeration,” Adams talks of kunoichi as “a product of [Yamada Fūtarō’s] vivid imagination,” while Hayes also speaks of “myth and misunderstanding.”6 There’s a certain sort of messianic tone to some of their writings, as if they were leading us to the enlightenment of history away from the delusion of literature, though that’s not of course how they actually frame the issue.

This, I’d suggest, is merely one more piece of evidence for these guys’ collective cluelessness as historians, since most serious scholars have long understood that the literary and the historical work together in a variety of subtle ways. The French philosopher Paul Ricoeur, for instance, speaks of the “conjoint effects of history and fiction on the plane of human acting and suffering,” going on to point out that good history needs the imagination of literature to be successful, and the historical novel likewise needs history simply to exist.7

I have a very low tolerance for French philosophy in general, but Ricoeur is dead on the money here. In Japanese history, too, it’s worth noting the notion that you can clearly and consistently separate the literary and the historical is going to get you into trouble, especially when dealing with medieval warrior tales such as the Taiheiki and the Tale of the Heike, which are widely acknowledged to be both heavily romanticized and embellished.

The point, I suppose, is that going forward a prospective ‘ninja studies’ needs more flexibility in its approach, not least to stop simply dismissing the literary aspect of the ‘ninja’ phenomenon as merely the product of “vivid imagination.” Personally, I think we could do with a little more imagination these days.

Anyway, I’m done with the lunacy of the kunoichi for the time being. I may return to the topic as part of a study of the ‘ninja’ lore of the Yagyū clan at some point, but for now I want to move on to something different. I’d like, from the next post onward, to introduce the other major project I’m working on in my professional capacity, and explain how it connects to the ‘ninja’ thing in a variety of unexpected ways.

Polina Serebriakova and Danny Orbach, “Irregular Warfare in Late Medieval Japan: Toward an Historical Understanding of the ‘Ninja’” The Journal of Military History 84 (October 2020), p. 997.

Brian Hamnett, The Historical Novel in Nineteenth-Century Europe: Representations of Reality in History and Fiction (Oxford UP, 2011), p. 39.

Hamnett, The Historical Novel in Nineteenth-Century Europe, p. 39.

Linda Hutcheon, “Historiographic Metafiction” in Michael McKeon, ed., Theory of the Novel: An Historical Approach (Johns Hopkins Press, 2000), pp. 830-849.

I suppose if you needed a term, you could try “shitty history” or “incompetent history.”

Donn Draeger, Ninjutsu (1971; my copy, 1989), p. 103; Turnbull, Ninja: AD 1460-1650 (2003), p. 2; Adams, “Last of the Ninja” Black Belt Feb. 1967, p. 33; Hayes, The Mystic Arts of the Ninja (1985), p. 133.

Paul Ricoeur, Time and Narrative (1984) Vol. 1, p. 226; quoted in Hamnett, p. 48.

Thank you very much for such a detailed reply and for the recommendations on which anime are especially good to watch from a historical accuracy perspective. I've heard of Yoshikawa Eiji but not actually read any yet (my Japanese is at the level of a little duolingo so waaaaaay off reading a novel) so thanks for the tip and I'll see if I can feature one of his novels on my substack in the near future.

Thinking more broadly about history and historical fiction, both are categories of storyteller, it's just that the rules of engagement differ for both: History requires you to stop when you can't include a footnote to cite your source whereas Historical Fiction enables you to cross that line and imagine the possible, which can only be successfully done when you've thoroughly done your homework. I remember reading Amy Stanley's Stranger in the Shogun's city and thinking that this story was crying out for a historical fiction take given the gaps in the documentation to explain why Tsuneno acted as she did. Perhaps these genres of writing are not so opposed after all.

Thanks for writing this. Are there any historical fiction novels in English that you would recommend for reading about Japanese history? I suspect for many, reading historical fiction is how they learn history so it'd be good to promote/profile some which are more historically accurate.