Wreak Bloody Samurai Vengeance, or Listen to Your Mother?

The eternal dilemma (Part #2 of the tale of Manabe Rokuro)

Last time around we introduced the warrior Manabe Rokurō, the star of this very ‘ninja’-like print, and explained a bit about the True Chronicle of the Lord Regent (Shinsho Taikōki), the popular semi-fictional narrative to which the print is a companion illustration.

So what do we know about Manabe Rokurō, and how does he come to be trying to kill Oda Nobunaga?

A Tale of Tanba Province

The first thing to know about Manabe Rokurō is that he isn’t always Manabe Rokurō. Depending on the source, he’s also known as Gotō Rokurō Taifu or Chihara Rokurō Taifu.1 Here Manabe/Gotō/Chihara is the surname, Rokurō the personal name, and Taifu, meaning something like ‘Master,’ is an honorific official title awarded by the imperial court in Kyoto, though the title is a fairly low-ranking one. Many warrior clans had official court titles that were either awarded by the court for their deeds or which were hereditary, so the ‘Taifu’ title isn’t necessarily a sign that our guy was particularly important or had much to do with the imperial court on a daily basis. It seems as if our hero here is most commonly referred to with the surname Gotō, but, since the one consistent element in all of these is the name Rokurō, I’ll refer to him as ‘Rokurō.’2

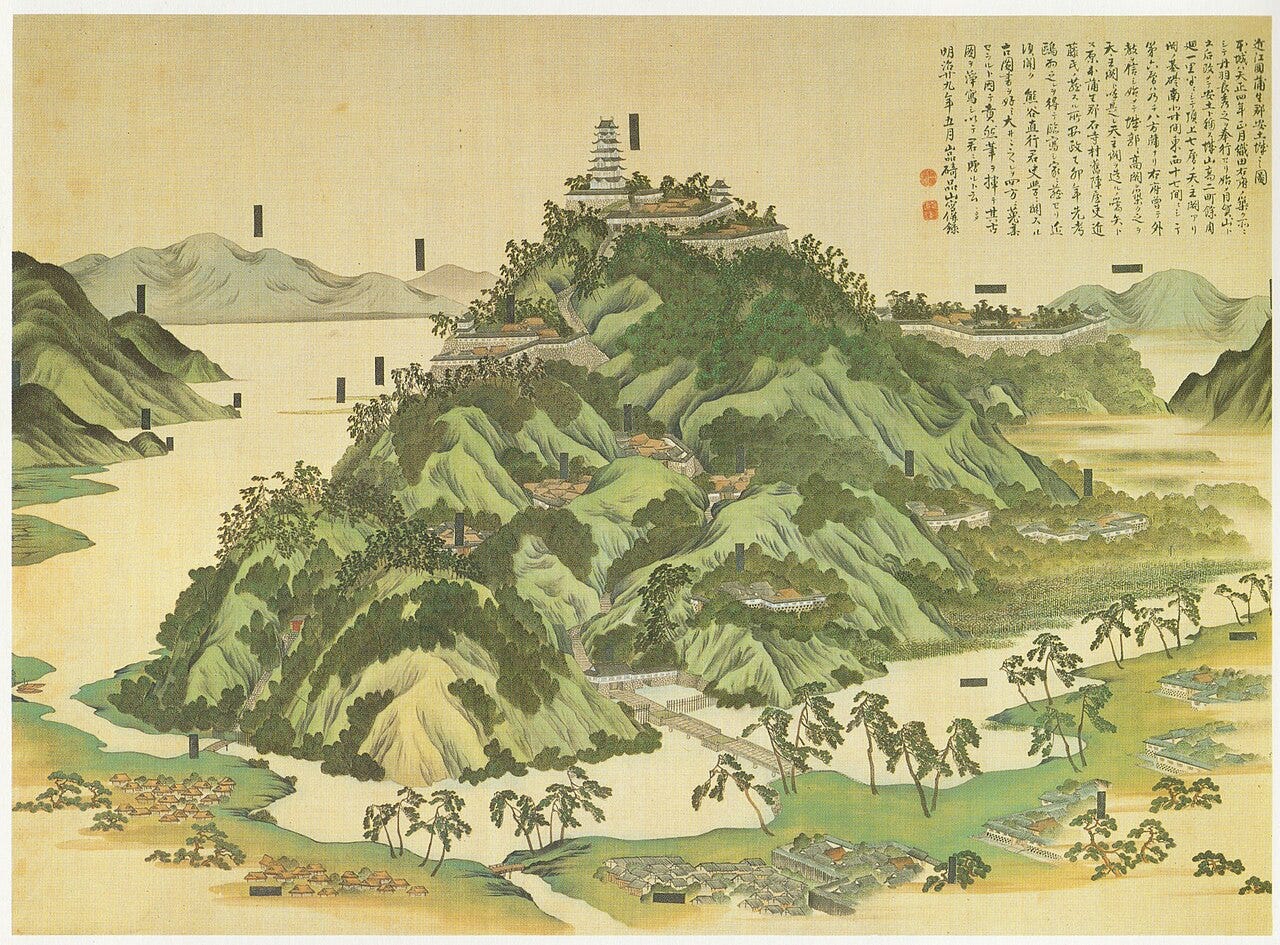

It’s unclear when Rokurō’s story was first recorded in Japan, although it appears as if it derives from local legends and/or folk-tales circulating in the province of Tanba. One of the premodern provinces of Japan, Tanba was to the north-west of the city of Kyoto, covering what is now modern Kyoto and Hyōgo Prefectures:3

It’s probable that these folk-tales were picked up by the kōdan storytellers of Osaka a province or two over, who then incorporated them into their acts, and by the mid-19th century these tales had then made their way into the pages of Shinsho Taikōki, which as I noted earlier seems to draw on kōdan storytelling for at least some of its material.

Just the Standard Samurai Treachery

As is often the case with folklore and local legends, there are several variations, so while I’ll mostly be using the version in the Chronicle of the Regent, I’ll also note where other accounts differ in a way that’s significant.

Anyway, the basic outline of Rokurō’s story is as follows.

We begin during the warlord Oda Nobunaga’s campaign of conquest to pacify the Kyoto area during the 1570s. As part of this, Nobunaga sends one of his military commanders, Akechi Mitsuhide, to pacify Tanba Province, which is ruled primarily by the Hatano clan and specifically by the warlord Hatano Hideharu.4 Hideharu puts up some initial resistance to Akechi Mitsuhide but, realizing he is outmatched, ultimately chooses to submit. In 1576, though, Hideharu betrays Nobunaga and rises up against him once again - a move that was not particularly uncommon among Warring States samurai, despite what you may have heard about ‘samurai loyalty.’

Before long, though, Hideharu realizes that this resumption of hostilities was a mistake, so he again offers his submission and travels to Nobunaga’s castle at Azuchi, in central Japan, to surrender and offer an apology. Hideharu is expecting to be forgiven and to be re-confirmed as the ruler of his lands in Tanba Province, because that is what Nobunaga has told him is going to happen.5 What actually happens, though, is that once Hideharu has arrived at Azuchi Castle Nobunaga has him executed, having clearly had more than enough of Hideharu’s shit.6

So far this is more or less accurate history, in that we know that all of the principal characters existed and that they did more or less do what is being described.

Call Your Mother. She Worries.

We then are introduced to Rokurō, who, perhaps to our surprise, is not a ‘ninja’ but a medical doctor, farmer, and former samurai. The ‘former’ bit is because Rokurō was previously a retainer to the Miyoshi clan of the capital region, and had fought for them with considerable distinction until his mother urged him to give up his military career.7 One version of the story, apparently recorded in Amata County in what used to be Tanba Province, has Rokurō’s mother pleading with him as follows:

I do not wish for you to be a warrior, achieving wealth and honor by slaying your foes and recording great deeds in battle. I have only your younger sister now, and so on whom will I depend in my old age if you should be killed? The pain of poverty and low status I can bear, but not the pain of losing you. If your ambition is to be a warrior, then seek such status once I am no more.8

This sets up one of the major themes of the story, of conflicting obligations and of putting your family’s needs above your own.

Like a good and filial son, then, Rokurō does what his mother asks. He resigns from the service of the Miyoshi clan and turns to medicine with a bit of farming on the side to get by, though the family income is greatly reduced by this choice and they are desperately poor. Even if he does not make much money off it, Rokurō’s medical practice is still significant for two reasons. First, according to Chronicle of the Regent, is because one of his patients turns out to be a lady-in-waiting to one of Nobunaga’s wives, and from her Rokurō discreetly picks up a lot about the layout of Azuchi Castle. Second is that Rokurō also happens to treat a samurai by the name of Fukui, Master of the Office of Waterworks (mondo). Mondo, as we shall call him, is a retainer of the Hatano who was wounded in battle against Akechi Mitsuhide’s forces.9 Rokurō sees to Mondo’s wounds and restores him to some semblance of health, at which the two form a close friendship; Chronicle of the Regent states several times that Rokurō and Mondo’s relationship was as close as if they were brothers.

As it turns out, Mondo’s most deeply-held desire is to avenge his former lord Hatano Hideharu, which means killing Oda Nobunaga. Mondo, though, realizes that his fighting days are over and he cannot do it himself, so he solemnly asks Rokurō, as a friend and brother, to accept the task of killing Nobunaga for him. Rokurō agrees to do so, but takes his time over actually carrying out the mission. At length, worried that word of their plan might get out and seemingly depressed over his physical debility, Mondo commits suicide by shooting himself in the throat. Rokurō is consumed with guilt, believing that the suicide was prompted by his delay in carrying out the assassination – which, to be fair, it kinda was.

And so Manabe Rokurō finds himself in a terrible dilemma. On the one hand is his filial duty to his mother, having sworn to her that he will be a warrior no longer. On the other is his duty to his friend and brother Fukui Mondo, a duty made all the more pressing by Mondo’s despairing suicide.

So what will Rokurō do next? Well, you’ve seen the Toyonobu print, so I think you know, but the fun is only just getting started. In our next installment we’ll cover how Rokurō goes about taking vengeance for his friend and comrade-in-arms, and we’ll also see what happens afterward, because the story only gets better from this point on.

Gotō Rokurō taifu 後藤六郎大夫; Chihara Rokurō taifu 千原六郎大夫. Of the three, Gotō seems the most common; as far as I can tell, it’s mostly Shinsho Taikōki that consistently refers to him as “Manabe.”

It isn’t particularly unusual for warriors to be known by several different names, by the way. This, as you can imagine, is a huge pain in the ass for scholars and translators (like me) working with pre-modern warrior tales.

Tanba 丹波; Kyoto 京都; Hyōgo 兵庫. As should be obvious, the pre-modern provinces don’t correspond to the modern prefectures.

Akechi Mitsuhide 明智光秀 (?-1582); Hatano Hideharu 波多野秀治 (?-1579)

Azuchi 安土; Azuchi-jō 安土城.

For the text of Shinsho Taikōki, I’m using an edition from 1909 published by Hakubunkan. If you read Japanese and want to view the text for yourself you can do so here, thanks to the amazing digital collections at the National Diet Library in Tokyo. The part I’m discussing starts on p. 597 per the book’s internal pagination or p. 321 using the viewer’s pagination.

Miyoshi 三好.

As recorded in Materials Relating to the History of Amata County (Amata-gunshi shiryō 天田郡志資料) (Rinsen Shoten, 1985), p. 540. Japanese text: 汝が武人となりて敵を殺し戦功を立てて富貴に至るは我が願ふ所に非ず。今は妹一人あるのみ。若汝死せぱ老年誰れにかよらん。貧賎は我之を苦とせざるも、汝と離るゝを苦となす。汝武士の望あらば母の死後仕官せよ。

Fukui Mondo 福井主水; probably fictional, so no dates. ‘Mondo’ is short for mondo no tsukasa (主水司), meaning something like ‘Master of the Office of Waterworks,’ which was an office of the imperial court that dealt with water supply. It was not unusual for warriors to be known by their official title rather than their personal name, and since no other personal name is given, we’ll just call him Mondo. The title was purely honorific and wouldn’t have implied any actual hydrological duties.

My favorite part:

“What actually happens, though, is that once Hideharu has arrived at Azuchi Castle Nobunaga has him executed, having clearly had more than enough of Hideharu’s shit.”