We’ve just seen that the idea that ‘ninja’ and samurai were mutually opposed social groups is very difficult to support using Japanese historical sources. Instead, if we want to understand how this claim originated, we’d do better to look at the political picture in Japan during the time that the modern ‘ninja’ emerged, namely the late 1950s and early 1960s. In the last post, we began doing that by looking at Shirato Sanpei’s widely-read manga Ninja: The Arts of War (Ninja bugeichō).

Kagemaru, Rebel Leader

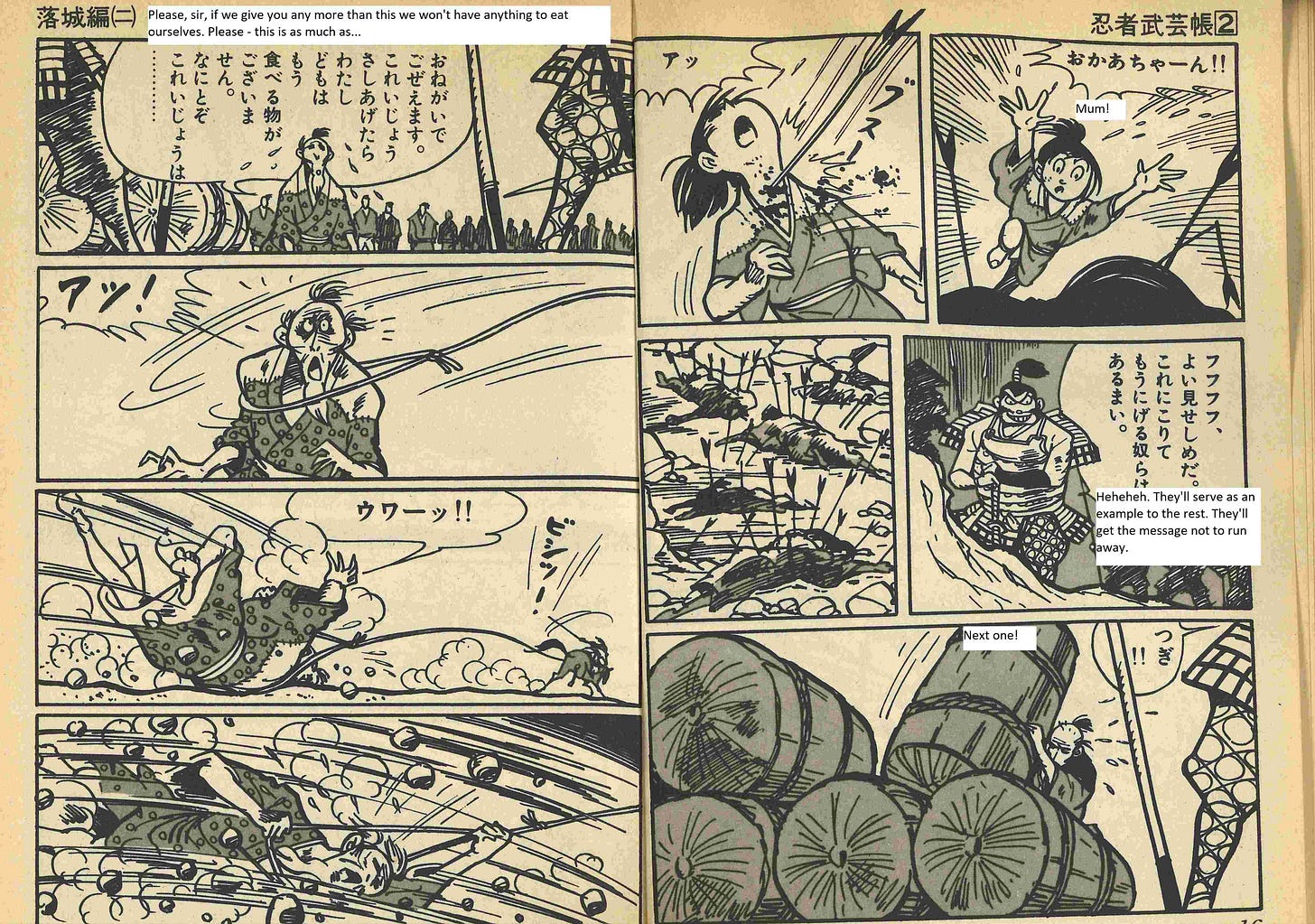

Last time around we found ourselves in northern Japan during the 1550s, where the scumbag usurper Lord Sakagami had raised taxes on the peasants by 30% and promised harsh punishment on all who tried to defy him. This is no empty threat, as a group of peasants who try to flee discover:

So it’s pretty clear that the samurai treat the peasants abominably, not only taking the fruit of their labors but casually murdering and torturing them at the drop of a hat.

Luckily, Kagemaru, Master of Shadows, is hanging around and decides to help the oppressed peasants out. Long story short, Kagemaru organizes the resistance, and, being a master of unconventional warfare, leads a successful peasant uprising that culminates in an assault on Lord Sakagami’s castle at the end of volume 2:

You’ll note the symbolism of the samurai weapons of spears and swords being overcome by simple farming implements such as hoes, wooden mallets, and bamboo spears. Lord Sakagami himself survives the uprising, escaping from the castle to become kind of like the recurring villain in the series, but his castle is literally razed to the ground; in one of the scenes shortly afterward we see the peasants removing the last of its stone foundation to clear land for them to farm.

So at first glance, then, it looks like The Arts of War is a plausible candidate for the trope originator, or at least for the idea that ‘ninja’ were involved in efforts by medieval peasants to fight back against marauding samurai. Of course, The Arts of War is fiction, but as I’ve shown, the major ‘ninja’ writers of the 20th century were not able to distinguish between works of fiction and historical evidence, so…

The Anpo Riots of 1960

We also need to take a look at what was happening in Japan during the publication run of The Arts of War, particularly if we want to understand what Shirato Sanpei might have been trying to do with his story of Kagemaru as a kind of guerilla fighter. The number one issue here would be the riots and massive protests surrounding the 1960 renewal of the US-Japan Mutual Security Treaty, usually referred to as the Anpo Treaty.1 This was a formal treaty outlining the terms and conditions under which US military forces could be stationed on Japanese soil. It had first been convened in 1951, during the US Occupation of Japan (which ended in 1952), and it was now, in 1960, coming up for renewal.

The renewal of the treaty was massively unpopular in Japan. Hundreds of thousands of people took to the streets to oppose its being re-upped by the Japanese parliament, and although opposition to the treaty was initially led by mostly left-wing groups such as the Japanese Student Union, by the summer of 1960 opposition to the treaty enjoyed the support of a variety of groups across the political spectrum. This even included some conservative pro-business groups, who preferred to focus on making money and staying out of potential military entanglements.

In the end, the demonstrations didn’t succeed in stopping the treaty, which was renewed as of June 23rd, 1960, though not without some parliamentary skulduggery by the Japanese Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke. The passing of the treaty in the teeth of broad-based popular opposition caused a great deal of public anger, and Kishi resigned as PM shortly afterward. It would also, in the years that followed, be a moment of real disillusionment for many of the groups that had opposed the treaty. If even that big a popular movement couldn’t make its will heard, it called into question what democracy even meant in Japan. For some of the more left-wing groups, failure to stop the treaty resulted in internal schisms and recriminatory finger-pointing, or even despair at the possibility of real change. Film director Ōshima Nagisa’s grimy and brutal work Cruel Story of Youth (June 1960), for instance, features a pair of juvenile delinquents getting into all kinds of trouble against the backdrop of the Anpo Riots. Neither of the two are actually interested in the politics; rather, both are essentially nihilists, with no real hope for the future or change. This, the story suggests, is a result of the failure of the previous generation of idealistic leftists, who failed to build a truly democratic society in the aftermath of the war.

Anpo and Ninja - An Unlikely Combination

What does all of this have to do with ‘ninja,’ you may ask? The simplest answer is that the manga The Arts of War was very popular among the student demonstrators who worked to oppose the Anpo Treaty, and appears to have been read as an allegory for the struggle of the anti-Anpo movement, though Nick Kapur writes that Shirato Sanpei himself denied that that was what he’d intended.2 Nevertheless, the idea that Arts of War was in some fundamental sense about the experience of the Anpo riots remained the dominant interpretation of the manga for some time afterward. In the afterword to vol. 2 of the 1976 edition, for instance, the literary critic Ozaki Hotsuki notes that he first came across The Arts of War at the height of the Anpo demonstrations. He goes on to draw a parallel between the manga and Anpo as follows:

Phrases such as ‘human advancement’ or ‘historical progress’ do indeed sound quite beautiful as reflections of the rational faculties of humanity, but in the real world they never happen so cleanly. Progress and reactionary pushback are two sides of the same shield, and just as he who is given life must always die, so too when there is progress there must also be setback, so to that extent there is meaning in the acts of human beings struggling as hard as they can simply to hold on to their lives.

The experience of the Anpo demonstrations taught us this in the arena of politics, but through the actions of Kagemaru in Ninja: The Arts of War, Shirato Sanpei set this problem before us in even more more concrete fashion.3

That is to say, Ozaki understands the peasant struggle against the samurai as being essentially an analogy for the Anpo movement’s struggle against the Japanese government, and by extension also the military presence of the US in Japan.

The point I’m trying to get across here, then, is that for a certain subset of mostly left-wing intellectuals in the 1960s, the ‘ninja’ was not the goofy cartoonish figure many of us might have thought him to be; rather, he was full of political nuance, a figure through whom it might be possible to say something profound about what had happened to Japanese society between the medieval period and the modern.

This point seems to have gone over the heads of most of the usual suspects for English-language ‘ninja’ histories, by the way - Draeger, Adams, and Hayes all seem to have been largely blind to this context, as was Turnbull until his 2017 Unmasking the Myth, which notes the over-representation of left-wing thinkers among early ‘60s ‘ninja’ media but doesn’t really do very much with that observation.4 To my mind, the above is a significant part of the intellectual history of the ‘ninja’ concept - it could hardly be otherwise, given the fact that the modern ‘ninja’ is basically a product of the ‘60s in Japan. It’s frustrating that so few writers seem to be aware of this context, still less think seriously about how it might have shaped the image of the ‘ninja.’

Shirato Sanpei and the ‘Ninja vs. Samurai’ Thing

Having said all that, I still have my doubts that Shirato Sanpei’s The Arts of War was the point of origin for the ‘class warfare’ hypothesis. For one thing, I can’t show that any of the usual suspects like Donn Draeger and Andrew Adams were even aware of The Arts of War, as there’s no obvious reference to it in their writings.5 For another, the way in which The Arts of War depicts the ninja-samurai antagonism doesn’t actually fit that well with the view we get in Hayes, Turnbull, et al.

You can, I suppose, find the outline of the ‘class warfare’ hypothesis in The Arts of War - Kagemaru is a ‘ninja,’ and he leads the peasants against their samurai oppressors, so you’re sort of in the general ballpark. But at the same time, the relations among peasants, samurai, and ‘ninja’ in The Arts of War don’t actually match all that well with the notion that ‘ninja’ were peasants who learned to fight dirty to defend themselves, or that noble samurai hated ‘ninja’ for their low-born, cowardly way of fighting. The Arts of War never actually suggests, in fact, that the peasants themselves are ‘ninja.’ Kagemaru leads them and organizes them into an effective fighting unit, but the distinction between peasant and ‘ninja’ is still fairly obvious. What’s more, Kagemaru himself isn’t the only ‘ninja’ in the story, because there are some working for the other team too. The sister of the evil Lord Sakagami, Hotarubi - literally, Firefly - is in fact a ‘ninja’ herself, and a very effective one. She’s capable of tracking Kagemaru, and also of seriously injuring the young warrior Jūtarō in combat (she cuts his arm off two pages later):

Further reinforcement of this point comes after Lord Sakagami is driven out of his castle by the peasant uprising, at which Hotarubi trains her brother in the ‘ninja’ arts. Sakagami himself then becomes a ‘ninja’ too, jumping up to the tops of trees, clad in chain-mail armor, and throwing shuriken at his enemies. In other words, in The Arts of War ‘ninja’ skills are not directly connected to peasant status at all; in fact, it seems like ‘ninja’ are more of an independent class of their own, capable of fighting both for and against peasants and samurai depending on their inclinations.

So, as politically charged and fun as The Arts of War is, we probably have to look elsewhere to establish where the ‘class warfare’ hypothesis came from. Fortunately we don’t have to look too far, because my money is on another product of the early 1960s, the ‘ninja’ novel Shinobi no mono from 1960 and the smash-hit movie of the same name from 1962.

For next time, then, get your popcorn, and we’ll take a close look at maybe the most influential ‘ninja’ movie of them all.

Because the treaty’s name in Japanese was Nichi-Bei anzen hoshō jōyaku 日米安全保障条約. Modern Japanese likes to shorten things a lot, so the an of anzen and ho of hoshō were smushed together to give us ‘Anpo.’

Nick Kapur, Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. (Harvard UP, 2018), p. 180.

Ozaki Hotsuki 尾崎秀樹 (1928-1999), “Shirato’s View of History and Ninja: The Arts of War” in Shirato Sanpei, Ninja bugeichō (1976), pp. 216-217. Japanese text: 人類の進歩とか歴史の発展なとという言葉は、人間の理性をうつしていかにも美しくひびくが、現実の動きはけっしてそのようなきれいごとですむものではない。進歩と反動は楯の両面であり、生ある者に死が必然であるように、発展にも挫折はつきもので、それだけにまた人間のぎりぎりの生も意味をもつのだ。

安保の体験はそれを世事的状況の中で教えてくれたが、白土三平は「忍者武芸帳」の影丸の動きをとおして、さらに具体的に問題を投げかけたのである。

Stephen Turnbull, Ninja: Unmasking the Myth (2017), pp. 147-48. Almost inevitably there’re some sloppy errors here again; The Arts of War is dated to 1957, two years too early, and Turnbull wrongly claims that The Arts of War is “a ninja manga only in its title” because the characters in the story are not directly referred to as ‘ninja.’ This is a very odd assertion to make, because Hotarubi refers to Kagemaru as a ‘ninja’ (忍者) in vol. 1:246, and the characters 忍者 are explicitly read as ‘ninja’ throughout vol. 4.

As I’ll explore in the next post, I’m not really sure how far Draeger and Adams were able to read Japanese. A lot of subsequent ‘ninja’ historians definitely can’t, or have far more limited skills than they would like you to believe.