The Intellectual Incoherence of 'Ninja vs. Samurai'

In which Stephen Turnbull forgets his own arguments

One of the things you have to be able to do as an academic is to understand what your materials are telling you. Call it pattern recognition, connecting the dots, seeing the big picture, whatever - a good scholar is able to pull together disparate sources and derive from them a coherent argument. The majority of ‘ninja’ writers, it won’t surprise you to know, are bad at this - a lot of the time, they seem not to fully grasp what their own materials are telling them.

The ‘samurai vs. ninja’ thing is a good example of this failing, because as a conceptual tool for understanding medieval warfare it’s completely incoherent, even if we take everything in the conventional ‘ninja’ histories at face value. What’s especially frustrating is that ‘samurai vs. ninja’ is not just incoherent, it’s obviously incoherent. You don’t need a particularly deep background in Japanese language or culture to figure this out - you just need the ability to remember what a book is saying for more than a few pages at a time.

The Art of Obliviousness

Let’s explore this in the works of Stephen Turnbull, starting with his 1991 book Ninja: The True Story of Japan’s Secret Warrior Cult. The book begins with Turnbull presenting the ‘dirty work’ hypothesis:

This was the dark side of the samurai tradition, the world of the warriors called ninja, who delivered victory by a process that reversed all that the samurai stood for. Ninja did not face squarely on to their opponents, nor did they allow them the opportunity of a challenge. In sharp contrast to the samurai ideal, the ninja represent the sole example of the use of paid mercenaries in samurai history, and there was no particular honor attached to being the first into the battle.1

The problem is that this clear statement of a “sharp contrast” between ‘ninja’ and samurai is immediately contradicted by almost all the examples of military operations Turnbull presents to his readers.

Carrying on through Secret Warrior Cult’s introduction, we come to its first chapter, helpfully entitled “The First Ninja.” The second example of supposed ninja-type warfare Turnbull presents in this chapter is that of the celebrated warrior Minamoto no Raikō, slayer of the demon Shuten Dōji in a very famous medieval story.2 Shuten Dōji, a tale first recorded in the 14th century, tells of a flesh-eating demon in the mountains outside of Kyoto who begins kidnapping noblewomen in order to eat, enslave, and/or have sex with them. His reign of terror is ended by the warrior Raikō, who gains access to Shuten Dōji’s palace with a band of stout warriors by disguising themselves as traveling priests. They then get the demon drunk on magical sake and proceed to kill him.

As he segues into this episode, Turnbull notes the importance of:

disguise, a means of deception that was to be found in many ninja stories in the centuries to come. A similar action under the cover of disguise appears in another old Japanese legend: that of General Raikō and the ogre of Ōeyama [i.e., Shuten Dōji].3

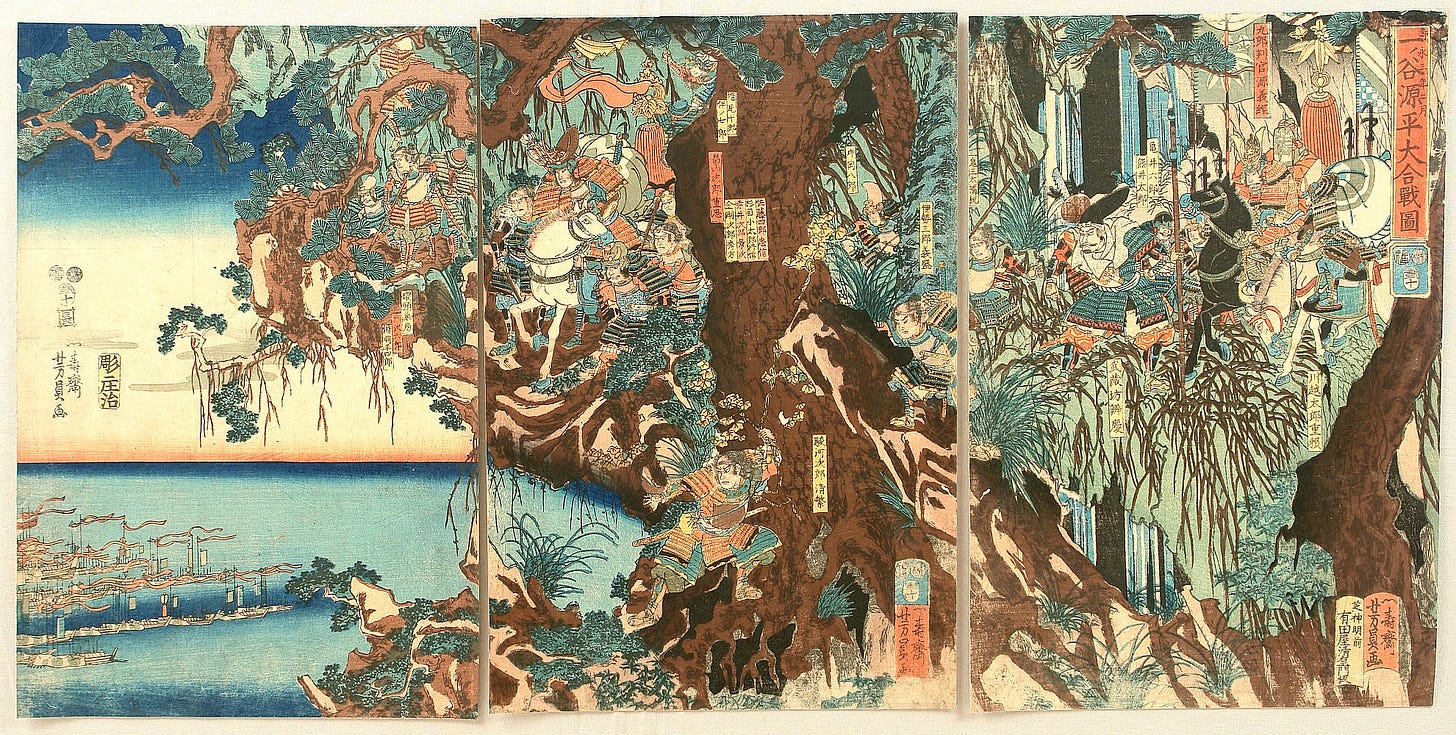

There are any number of prints depicting the Shuten Dōji story; here’s one I found almost at random:

Raikō himself is in the top-right of the print, and as more discerning readers may observe, his weapons and armor make him look distinctly…well, samurai-ish. I might also add that the Minamoto clan was one of the two most prominent warrior clans of the mid-to-late Heian period, and the ancestral line of pretty much every Shogun in Japanese history.

As you can see, we have a problem right from the off. After telling us that samurai would never use underhand tactics and despised ‘ninja’ for doing so, almost all of Turnbull’s next few examples are very obviously ‘samurai,’ doing exactly what Turnbull said the samurai didn’t do.

When is a Samurai not a Samurai? When He’s Like a Ninja

From there, we go on to cover a couple of examples from the famous war tale Tale of the Heike. This is an account of the Genpei Wars of 1180-85 between two prominent warrior clans, the Taira and the Minamoto. The Tale of the Heike remained popular for centuries after its composition, and it provides some of the most celebrated episodes of samurai glory in all of Japanese history. One such episode is the warrior Minamoto no Yoshitsune’s assault on the Taira fortress at Ichinotani in 1184. Yoshitsune, brother of future Shogun Minamoto no Yoritomo, leads his horsemen down what the Taira forces had considered an unscalable cliff, catching the Taira completely by surprise and handing them a crushing defeat.

This assault Turnbull describes as “the only case of anything resembling a ‘ninja attack’” in the Heike. This is nonsense on its own terms - there are plenty of ambushes and the like in the Heike - but I want to draw your attention to the hedge implied by the phrasing “resembling a ninja attack” (emphasis mine). Note that Turnbull isn’t saying that Yoshitsune is a ‘ninja,’ rather than he and his fellow samurai are doing something akin to what ‘ninja’ do. This same hedge is repeated several times over the next few pages:

Kawara Jirō and Kawara Tarō abandoned their horses for a night raid…although they are behaving like ninja…

We will examine in Chapter 9 the ninja-like role of Yoshitsune and his followers…

Kusunoki Masashige, whose use of unconventional and ninja-like tactics…4

We’re barely twenty pages in to the book, and already Turnbull appears to have forgotten his own argument about ‘ninja’ tactics being the antithesis of the ‘samurai way,’ because he’s just given the reader no fewer than four examples of samurai doing exactly what ‘ninja’ are supposed to have done. The use of the hedge phrase “ninja-like” suggests to me that Turnbull was aware on some level that his conceptual map was running into trouble, but where a better historian might have paused to re-assess his project, Turnbull just carries on as if nothing had happened.

The Emperor’s Ninja: A Bunch of Samurai

Turnbull’s next chapter, “The Emperor’s Ninja,” consists mostly of episodes drawn from the Taiheiki, another famous yet heavily-embellished war chronicle from the late 14th century. Much of this chapter focuses on the activities of the famous warrior Kusunoki Masashige, whose unconventional strategies proved very effective against the numerically superior Hōjō forces. As Turnbull puts it:

What is now regarded as Masashige’s ninjutsu was in fact very skillful guerilla warfare, marked by surprise attacks, night operations, and distinguished above all by Sun Tzu’s insistence that warfare was the art of deception. The conditions which governed the conduct of the Nanbokuchō Wars [of 1336-1392] lent themselves particularly well to this mode of warfare, and enable us to see for the first time in samurai history the successful operation of the art of the covert warrior.5

It’s still quite early in the book, but it’s clear that the picture Turnbull is attempting to paint of medieval warfare is a conceptual mess. Thirteen pages earlier, remember, the reader was assured that:

There was no place in this quixotic dreamworld [of samurai values] for a knife in the back, or the destruction of a fortress at dead of night by warriors who were never seen by their victims.6

But now we have Kusunoki Masashige, one of the most famous samurai heroes of all time, engaging in “surprise attacks [and] night operations.”

I also want to draw attention to Turnbull’s claim that studying the Nanbokuchō Wars enables us to see covert warfare succeeding “for the first time in samurai history.” This is an odd claim, as it seems to suggest Turnbull has forgotten about the examples of successful clandestine warfare he provided, uh, two pages earlier in Chapter One.

So, let me see if I have this straight:

Samurai didn’t engage in underhand tactics, except when they did, which was quite often.

‘Ninja’ were the antithesis of the samurai, but Masashige and his allies were “The Emperor’s Ninja,” while also being famous samurai.

The Nanbokuchō Wars of 1336-1392 provide the first successful use of covert warfare by samurai, even though samurai didn’t do covert warfare. The first use, obviously, except for Yoshitsune, Raikō, and all of the earlier examples of covert warfare Turnbull provided in the previous chapter, which apparently we’ve forgotten about or which don’t count, for some reason.

Like I said, a conceptual mess.

Ninja: An Unnecessary Hypothesis?

This just gets weird after a while. It’s a bit like reading a book on French cuisine that insists that the French don’t eat at McDonald’s, and then finding that the next eight illustrations are all of French people eating Big Macs. Or something. You get what I’m trying to say.

The main thing that derails Secret Warrior Cult is that Turnbull cannot reconcile his modern understanding of the ‘ninja’ with the actual content of the historical sources he’s working with. Simply put, his own sources mostly contradict his argument, but where a better historian would take a step back and re-evaluate, Turnbull pushes ahead regardless and ends up with a book that’s conceptually incoherent. I’d argue, in fact, that Secret Warrior Cult would have been a much better book if Turnbull had simply dropped the notion of the ‘ninja’ entirely. Without the ahistorical conception of ‘samurai honor’ or the need to strain to find ‘ninja-like’ activities, we could have had a reasonably decent account of unconventional warfare in medieval Japan.

More recent ‘ninja’ writers do seem to have begun to acknowledge the problem of distinguishing between ‘ninja’ and samurai. Anthony Cummins, for instance, writes in 2012 that:

It is a misconception that the ninja are a separate force outside of the samurai, as they are in fact a subgroup of the samurai […].7

This, to me, raises two important questions. The first would be: why do we need the concept of the ‘ninja’ at all? Wouldn’t we be better off simply revising our understanding of medieval military practice, so that it’s more accurate with regard to what samurai did and didn’t do? But that, I think, is a question that needs its own post and some more time to develop.

The second question would be this: If the idea of ‘ninja’ and samurai as mortal enemies isn’t there in the historical sources, where did it come from, and when did it start?

I have a pretty good idea of the answer to that question, so that’s where we’ll go in the next couple of posts.

Turnbull, Secret Warrior Cult (1991), p. 10.

Secret Warrior Cult, p. 16. I could point out that the Shuten Dōji story is obviously fictional - it features a big red demon whose head flies around after it’s been cut off - but honestly, there are so many things going wrong here that it’s almost overkill to note that.

Secret Warrior Cult, p. 16.

Secret Warrior Cult, pp. 19-21.

Secret Warrior Cult, p. 22.

Secret Warrior Cult, p. 9.

Cummins, In Search of the Ninja: The Historical Truth of Ninjutsu (History Press, 2012), p. 11. Not sure what explains the use of the present tense.

I’m curious if you’re ever crossed paths with Mr. Turnbull, like at a conference, or on a remote forest road at night?

I have been following you for a while and am still trying to figure out the early motivation for the nonsense writing outside of "ninjutsu" teachers doing branding