We saw in the previous post that ninjutsu instructor Hatsumi Masaaki played a major role in shaping English-speaking readers’ ideas of what the historical ‘ninja’ were. We also saw that a significant number of English-language ‘ninja’ writers were misguided enough to rely on Hatsumi’s 1964 children’s book, Ninja Skills Illustrated, as a primary source even though it contains large sections of obviously fantastical material.

Hatsumi has written other books, of course, but I think it’s useful to focus on Ninja Skills Illustrated because its influence is not at all obvious. I can’t really see, for instance, how a non-specialist reader could figure out that Draeger and Turnbull were using a children’s book as a source. Draeger never discloses his sources at all, and even though Turnbull’s 1991 Secret Warrior Cult does have end-notes and a bibliography, you would have to know Japanese for the title Shōnen no tame no ninja, ninpō gahō to be at all meaningful. Even then, you might not realize what the book actually is, because in citing it Turnbull omitted the “for kids” (shōnen no tame no) part of the book’s title:

Luckily for you people, I’m (a) bloody-minded enough to track all of the above down, and (b) have the resources of a major US research library at my fingertips. And so here we are.

The ‘Big Sticky Ball’ Approach to Writing History

Ninja Skills Illustrated also reveals quite a lot about what appears to be Hatsumi Masaaki’s philosophy of history, if that’s not too grand a term.

I don’t know if any of you ever played the mid-2000s Japanese video game Katamari Damacy, but it provides a useful model for thinking about how ‘60s ‘ninja’ lore tended to get made. (Bear with me on this, I know where I’m going. I think.) Katamari Damacy is a very quirky game, in which you play as a giant sticky ball that rolls around the landscape schlooping up all sorts of objects as you roll over them.

I’d like to suggest that this is a fairly good mental model for how Hatsumi went about building much of the supposedly historical ‘ninja’ lore – he rolled around the media landscape of 60s Japan, picking up bits and pieces from whatever fictional works he happened to bump into, and incorporating them into his growing sticky ball of ‘ninja’ lore.

OK, so maybe the metaphor needs some work, but hopefully you get what I’m saying. To make the point in more concrete terms, we can see in Ninja Skills Illustrated that Hatsumi is really leaning into popular ‘ninja’ media from the early 60s, notably the TV series Samurai Detective and the Shinobi no mono series of movies. There are black-and-white stills from both works throughout the first 30 or so pages of the book, for instance, and p. 3, the first bit of copy in the book and the only color plate, is a big splash of actor Ōse Kōichi in his role in Samurai Detective:

Along these lines the second major part of the book, after Hatsumi’s introduction, is in fact a transcript of a sit-down with Hatsumi and the two lead actors of Samurai Detective. Samurai Detective (in Japanese, Onmitsu kenshi) was a hugely popular TV series shown in Japan between 1962 and 1964. The main character, Akikusa Shintarō (played by Ōse), is the secret half-brother of the Shogun during the Edo period, and spends his time traveling around Japan rooting out those who dare to threaten the stability of the Tokugawa government. His sidekick, the second main character, is an Iga ninja named Tonbei, played by the actor Maki Fuyukichi.1

I Think I’ll Try Defying Gravity

On one level this sort of thing is just savvy marketing on Hatsumi’s part, a bit of clever corporate synergy. You can’t blame him for piggybacking on a popular TV show to boost his business; a man gotta eat, after all. But I can’t shake the feeling that it’s more than that, that on a more subtle level Hatsumi is trying to create the impression that these fictional shows are basically accurate accounts of what the historical ‘ninja’ actually did. In other words, he’s engaging in a classic ‘ninja’ history maneuver and using fictional works to support historical claims.

Maybe it’s helpful to look at part of the transcript of the sit-down to get a sense of what I mean:

(Ōse) The character I play, Akikusa Shintarō, is known as a ‘samurai detective’ (onmitsu kenshi), so…does that make him a ‘ninja’?

(Hatsumi) Yes, it does. All of the Tokugawa government’s detectives (onmitsu) were ninja, you see.2

All of them? OK then. This is one example of something that happens a few times in the interview: the ‘ninja’ actors mention things in their fictional show, and each time Hatsumi assures them that yes, the things in the show are indeed things the historical ‘ninja’ did and were. The idea that the Tokugawa secret police were ex-ninja, for instance, is pretty widespread in the English literature, and I can’t shake the feeling that there’s a good chance that that claim owes more to the popularity of the completely fictional Samurai Detective than to any solid historical evidence.

Another example:

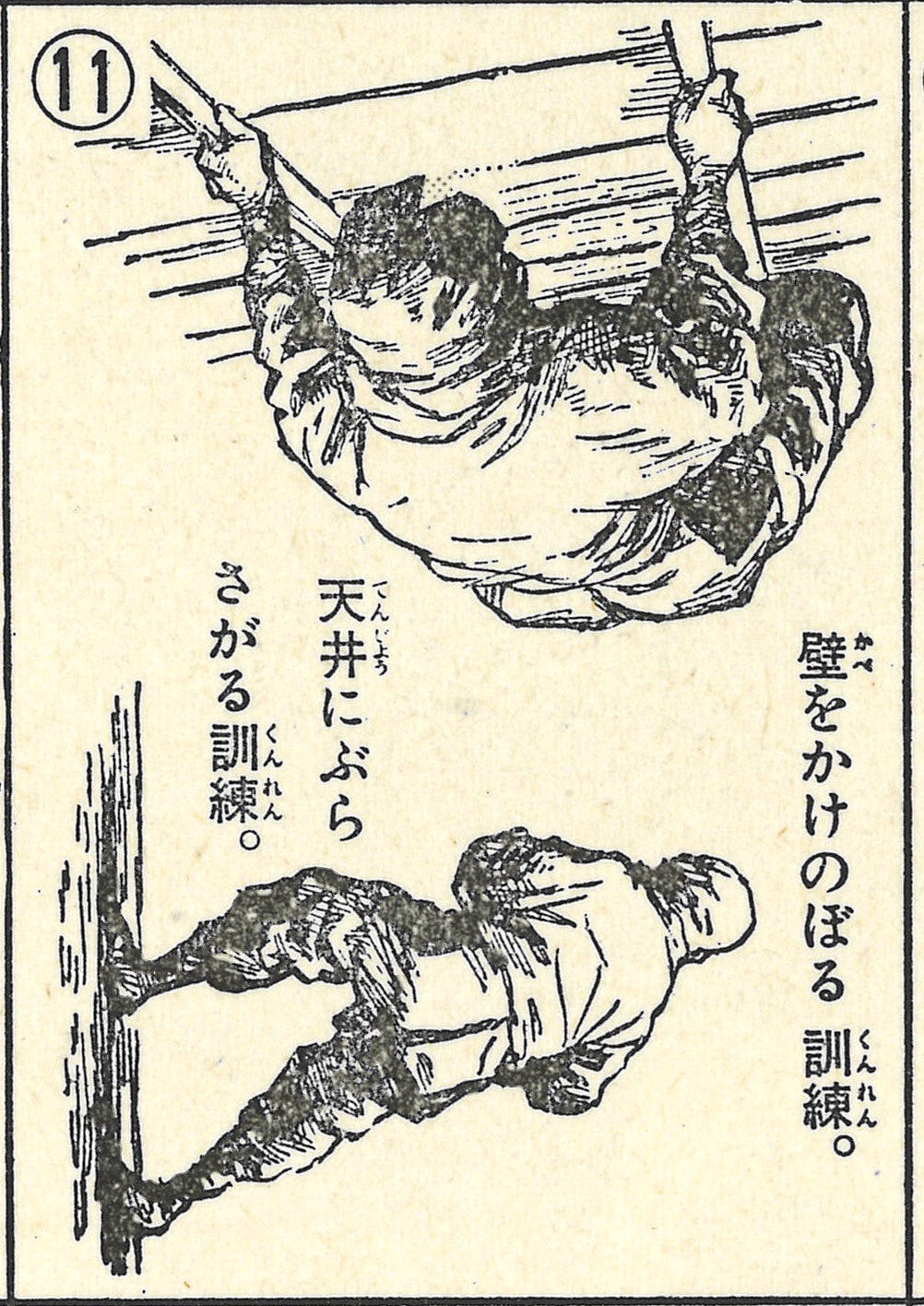

(Maki) We quite often have scenes where ninja sneak in and hang on to the underside of the ceiling. I ran an experiment myself to see if you could actually do that. Obviously I rigged up some points where I could brace my feet and hold on with my hands.

(Ōse) Oh, and on top of that, we put a futon below him, so that he could let go and fall at any time. (laughs)

(Maki) I had myself timed with a stopwatch. Five seconds flat, then THUMP.

(Hatsumi) No, you know, five seconds is quite impressive. The ninja of old were able to hang from the ceiling for extended periods of time because they used miniature tools, you see.

(Ōse) Well, there’s also that the ceiling of a room is the kind of place where you’d be immediately noticed. You hide there, you’d be found.

(Maki) I’d be like, “oh, good evening, my apologies for disturbing you!” (laughs) Guess I’m not cut out to be a ninja.3

As you can see, the closing lines of the quoted exchange suggest that the actors are politely disbelieving of Hatsumi’s claims; Ōse immediately realizes that, as stealth techniques go, hanging from the ceiling in full view of the inhabitants of a room would be less than optimal, and as Maki found, in practice your strength would give out very quickly.

This exchange is particularly interesting when read in conjunction with Turnbull’s attempt to explain the presence of those ludicrous ‘war machines’ in Ninja Skills Illustrated and Stephen K. Hayes’ account of Hatsumi’s explanation for the fantastical elements in the same book, that they were just there to humor the masses. It’s admittedly a small sample here, but it’s striking that most of the people we’re looking at here realized pretty quickly that Hatsumi had a habit of making claims that were implausible. Seemingly even Turnbull and Hayes, both of whom were well-disposed toward Hatsumi, were willing to admit that Hatsumi had put things in print that had a somewhat strained relationship to historical truth. The obvious conclusion would have been that Hatsumi was not a reliable source, but I doubt either writer would have viewed that as a palatable conclusion at the time.

Good History Starts with Fiction

As so often in ‘ninja’ history it’s not just that Hatsumi was unreliable, it’s how he was unreliable that’s most interesting. In reading his work, I’m left with a strong sense that Hatsumi’s methodology of ‘ninja’ history was heavily influenced by contemporary films, TV, and novels. Basically, as far as I can tell, Hatsumi would see something in pop media, and then, without missing a beat, would add it onto his big sticky ball of ‘ninja’ lore as if it were a real thing.

This might seem unlikely, but more recent scholarship in Japan has provided other examples of the the fiction -> history pipeline at work within 1960s ‘ninja’ lore. Both Yamada Yūji and Yoshimaru Katsuya, for instance, have recently argued that shuriken were never a weapon used by the historical shinobi.4 The association, famous as it is, originates in TV shows and movies from the late 50s and early 60s, or so they argue. Hatsumi, by contrast, features shuriken everywhere in his purportedly historical accounts of the ‘ninja.’ In fact, the section in Ninja Skills Illustrated immediately after the one I’ve just quoted contains this gem:

(Maki) So, how many shuriken did a ninja walk around with?

(Hatsumi) Nine. This is because the people of old considered nine to be the supreme number […]5

But Yamada and Yoshimaru say that the historical shinobi didn’t use shuriken at all. Knowing that, we’re left with only a few possible interpretations regarding Hatsumi’s very specific claim about ‘ninja’ carrying nine shuriken:

Hatsumi is correct - there is some historical evidence confirming shinobi use of shuriken of which Yamada and Yoshimaru are unaware.

It’s not possible to tell - the absence of evidence means we cannot decide for certain either way.

Yamada and Yoshimaru are correct - ‘ninja’ use of shuriken is indeed confined to the realms of fiction. It would follow that Hatsumi’s claims about these weapons are, intentionally or not, representing fictional tropes as if they were historical fact.

My own hunch is that #3 is indeed correct, in large part because of what can be seen in other sections of Ninja Skills Illustrated concerning Hatsumi’s approach to history. There’s one section in particular, concerning the fictional ‘ninja’ Sarutobi Sasuke and Kirigakure Saizō, that I want to talk about. This is the section that Turnbull missed when he was using Ninja Skills Illustrated as a source, no doubt to his lasting embarrassment, because it would have made clear to him that the account of Kirigakure Saizō he went on to present as historical in no fewer than four of his books was in fact fiction.6 Leaving that aside, in this section Hatsumi makes the very dubious claim that the well-known Sarutobi Sasuke was in fact based on a real ‘ninja’:

The ninja Sarutobi Sasuke, one of Sanada’s Ten Heroes, is in fact a fictional creation, and in the same way Kirigakure Saizō was not someone who actually existed. However, there was a model for Sarutobi Sasuke. This was a genin [low-ranking ninja] with the nickname Kizaru, who served Momochi Sandayū of Iga, and whose real name was Kōzuki Sasuke, and Sarutobi Sasuke was in fact based on this person. The real Sasuke was from Shimotsuge, so he was called Shimotsuge Kizaru [lit. tree monkey], and was famous for his jumping abilities.7

The bit from “However” onward appears to be referring to a section in Book 1 of the ‘ninja bible’ Bansen shūkai, which lists people who were supposedly skilled in the arts of stealth, among which we find the name Shimotsuge Kizaru. I have no idea what the source is for the claim that the guy’s real name was “Kōzuki Sasuke,” though it’s repeated all over the internet. I do notice that “Kōzuki Sasuke” is strikingly similar to another name that appears in the Bansen shūkai list, Kōzuke Sa[suke?], and it’s possible that that’s where it comes from, a mis-reading or garbled version of another name in the same list.8

But even if we grant Hatsumi’s premise that this Shimotsuge Kizaru was the model for the fictional ‘ninja’ Sarutobi Sasuke - and we shouldn’t, because this is obviously conjecture and Bansen shūkai is not a reliable source - this is still not a compelling argument. The thinking behind it appears confused, something like - OK, yes, the ‘ninja’ exploits of Sasuke and co are fictional, BUT if there was a real person on whom they were based, THEN Sasuke’s stories actually become real, because of the transitive properties of…something.

I’m being a bit facetious in characterizing the argument that way, admittedly, but the “based on” argument is not a strong one. For one, it fails to account for the many possible points of slippage between reality and fiction. When fictional works base their characters on real people they can do so in many different ways, from extremely close to life (think Charles Foster Kane as representation of William Randolph Hearst), to works where the name of a real person is used but the events in the film are pretty much 100% fictional. Abraham Lincoln certainly existed, for example, but I wouldn’t recommend you approach Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter as a historical documentary.

The “based on” thing, in short, is not a serious historical argument, at least not as Hatsumi has made it here. It’s an under-argued and unconvincing attempt to hand-wave the use of fictional stories and characters in place of real historical evidence.

So you see what I mean, I hope, when I say that the fiction comes first, that it’s the novels, TV shows, and movies that are driving the historical claims. This sort of thing is another reason why it’s worth spending time on Hatsumi’s children’s book – it’s a lot more revealing than he might have realized about the disjunction between what he was claiming to do and what he actually was doing.

This extensive confusion between fictional and historical material in ‘ninja’ history is one of the reasons I find the whole field so fascinating, as you will probably have realized. So, in our next post I’d like to explore this topic in a bit more detail by looking at another example of an alleged fictional ‘ninja.’ This is the evil sorcerer Nikki Danjō, star of a mid-Edo play who would enjoy an unexpected afterlife after being re-claimed as a ‘ninja’ a couple of hundred years later.

Kanji: Akikusa Shintarō 秋草慎太郎, played by Ōse Kōichi 大瀬康一 (1937-), and Tonbei 遁兵衛, played by Maki Fuyukichi 牧冬吉 (1930-1998).

Hatsumi et al., Ninja Skills Illustrated, p. 17. Japanese: 大瀬:わたしのやっている秋草新太郎も隠密剣士というんだから、やっぱり忍者でしょうね。初見:そうですね。幕府の隠密はすべて忍者ですからね。

Hatsumi et al., Ninja Skills Illustrated, pp. 17-18. Japanese: 牧:よく、忍者が天井うらに忍んでいる場面がありますね。このあいだ、じっさいにやれるかどうか、わたしが実験したんです。もちろん、足をふんばるところ、手でつかむところをつくりましてね。大瀬:おまけに、いつ落ちてもいいように、下にフトンをしいてね。(笑い)牧:ストップ・ウオッチではかってもらったら、5秒フラットで、ドスン!初見:いや、5秒なら、りっぱなものです。昔の忍者が長時間天井うらにぶらさがっていたのは、小道具を用いたからです。大瀬:それに、天井というのは、よく目につく場所ですからね。あんな所にかくれていてもすぐ見つかるでしょう。牧:見つけられたら「コンバンハ、おじゃましてます」(笑い)これじゃ、忍者にならないね。

See also Yoshimaru, Ninja to wa nani ka (2023), pp. 331-342.

Hatsumi et al., Ninja Skills Illustrated, p. 18. Japanese: 牧:忍者は、手裏剣をなん枚くらいもちあるいていたんですか。初見:九枚です。これは、昔の人は九が最高の数字だと考えられたからです。

It’s this story, and it’s featured in Turnbull, Secret Warrior Cult (1991), p. 54; Ninja: AD 1460-1650 (2003), p. 32; Warriors of Medieval Japan (2008), p. 180; and the children’s book Real Ninja (2008), pp. 33-34. Turnbull’s cited source in 1991 was Hatsumi’s Ninja Skills Illustrated, so he should have known the story was fictional.

Hatsumi et al., Ninja Skills Illustrated, p. 37. Japanese: 真田十勇士のひとり、忍者猿飛佐助は、じつはつくり話で、同じく霧隠才蔵も実在の人物ではなかった。しかし、猿飛佐助のモデルはいた。伊賀の百地三太夫につかえる下忍であだなを木猿、本名を上月佐助、この人をモデルにしてつくられたのが猿飛佐助というわけ。ほんものの佐助は出身地が下柘植なので、下柘植の木猿とよばれ、飛び技で有名だった。

下柘植ノ木猿 - dates unknown, and possibly fictional; the ‘Kōzuke’ name is 上野ノ左. See here for the original text of Bansen shūkai, bottom right of p. 27. To get a bit technical here, a lot depends on the interpretation of the graphs, which is difficult in the absence of any real context. Minami Yoshie’s translation of BSSK (p. 26) renders 上野 as ‘Ueno,’ which is certainly a possible reading, but I think it’s possible that ‘Kōzuki Sasuke’ is actually a garbled version of Kōzuke no sa [something] 上野ノ左. This could well be a slightly garbled title rather than a personal name, since it wasn’t uncommon for people in pre-modern Japan to be referred to by their (often honorary) titles rather than personal names. Possibly 上野ノ左 is a copy error for 上野の佐, meaning something like ‘the deputy commander from Kōzuke Province.’ A lot of the time working with BSSK involves a ton of guesswork, though, so who the hell knows.

When I read about Hatsumi's *Kizaru* (木猿), I can't not think about the word *nokizaru* (often written as 軒猿), mentioned in Bansen shūkai (like only twice?) or in Yamada (2016: 59), without further specification or verification. Is it (from the context) any possible that Hatsumi's "Kizaru" is some sort of garbled "nokizaru"?