One of the things a good historian needs to know is that words can change their meaning over time. We noted this in the previous post with reference to the term wakizashi, which now is usually understood to mean a short-sword but which, as Karl Friday pointed out, in medieval context could mean a weapon of any length.

Much the same point applies to the word shuriken. It’s fairly easy to find mentions of shuriken in both modern and pre-modern Japanese texts that predate the ‘ninja’ thing, usually written with the kanji 手裏剣 (meaning something like ‘sword within the hand’). So we can say right from the start that the word shuriken was used in Japan and was not a total invention, as we might suspect after having spent time around ninja historians.

I’ve looked at mentions of shuriken in various sources extending to about the mid-1960s or so, when the ‘ninja’ thing blew up in Japan. To address the point you all care about the most: I have never found a mention of the classic star-type shuriken outside of 20th century ‘ninja’ sources. This would suggest that the famous ‘ninja death stars’ were basically unknown in Japan until at least the 20th century, and most likely until the mid-1960s.1

In a somewhat odd parallel to the use of the term shinobi, much of the time shuriken appears in an adverbial clause (like, ‘throw as a shuriken’ or ‘use as a shuriken’), suggesting that shuriken was not necessarily a specific weapon but more a method or practice of throwing a blade. That said, in the examples we’ll see below the weapon in question is always a throwing-knife or, in some cases, a regular sword thrown as an improvised weapon, so it’s probable that over time the word shuriken came to be used as short-hand for a throwing-knife.

There are specific references to shuriken as throwing-knives or sword-throwing from at least as early as the mid-Edo period (1600-1867). The 1739 historical chronicle Jōzan’s Tales (Jōzan kidan), for instance, contains a mention from the late 16th century of a warrior named Yoshihiro throwing his sword as an emergency measure after being unhorsed:

He was knocked from his horse, but he drew his sidearm and launched it as a throwing-blade (shuriken ni utsu), striking one of the Inoue archers in the thigh…2

In similar vein, one of the more famous scenes of the fictional kabuki play The Paulownia Crest and the Golden Gate (Sanmon gosan no kiri, first performed 1778) has the thief Ishikawa Goemon launch a throwing-knife at an enemy. The target is the warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi (alias-ed in the play as Mashiba Hisayoshi), but he stops the blade with a wooden water-scoop.3 You can see a modern performance of the scene on YouTube here, with the knife-throwing at 2:40.

By the late 19th century, it appears that ‘throwing knife’ was established as shuriken’s primary meaning. James Curtis Hepburn, the American educator and linguist, includes the word in his 1894 A Japanese-English and English-Japanese Dictionary, defined as follows:

SHURIKEN シュリケン 手裏剣 n. A dirk, used by throwing. — wo utsu4

For those unfamiliar with Scottish terminology, a ‘dirk’ is a dagger. Confirming Hepburn’s definition is a brief note by the Japanese physician Miki Takeji on a performance of the Paulownia Crest play he had watched in February of 1896, where he describes the knife Goemon throws at Hideyoshi as a shuriken.5

It seems that this meaning of shuriken as a thrown knife remained fairly stable across the turn of the century and for the next few decades. The well-known anthropologist and folklorist Yanagida Kunio, for instance, mentions shuriken in his 1925 Life in the Mountains (Yama no jinsei), recording that the father of one of the villagers he interviewed carried a knife for throwing purposes:

Forty years ago the man’s grandfather had gone into the mountains and encountered a very strange old man. The man had white hair and was naked from the waist up, with a canvas-like material wrapped around his waist. The man smiled and came closer, and since he did not look like any normal man of this world, the grandfather grasped the handle of the small knife for throwing (shuriken-yō no chiisai tō no tsuka) he was carrying on his back, placed there as a precaution, and yelled “Come any closer and I’ll throw this at you!” (utsu zo).6

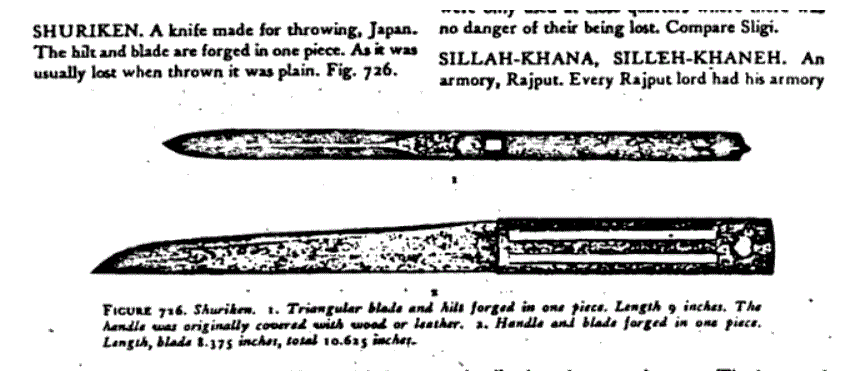

About ten years later in the American collector George Cameron Stone’s amazing A Glossary of the Construction, Decoration, and Use of Arms and Armor in All Countries and in All Times, Together with Some Closely Related Subjects (1934; yes, that’s the full title), we read:

SHURIKEN. A knife made for throwing. Japan. The hilt and blade are forged in one piece. As it was usually lost when thrown it was plain. Fig. 726.7

Fig. 726 is shown below, by the way. In case you can’t read the caption to the image, it says:

Shuriken. 1. Triangular blade and hilt forged in one piece. Length 9 inches. The handle was originally covered with wood or leather. 2. Handle and blade forged in one piece. Length, blade 8.375 inches, total 10.625 inches.

It’s worth noting that if Stone’s description of the shuriken as ten and a half inches is accurate, that would be a substantial weapon. For comparison, it would be around the length of a modern kitchen knife, much larger than the star-shaped shuriken we’re familiar with. It’s not hard to imagine that a blade that long could cause fatal wounds if thrown correctly.

We can still find examples of shuriken being used to mean ‘throwing knife’ in the postwar era and into the 1950s. Sakaguchi Ango’s serialized detective novel Meiji Enlightenment: Ango’s Detective Case Files (begun 1950), for instance, features a killing carried out with a shuriken:

Shinjurō examined the body. There was a small knife sticking out of Gohei’s gut. It had been thrown as a shuriken (shuriken ni mochiiru mono da). It had gone in all the way up to the base of the blade, but there had been little bleeding. […]

“So the shuriken just carved right through ‘im, all the way to the hilt, eh? - that kinda thing. I mean, a human belly’s pretty soft, but then again, it’s a bit harder than tofu, isn’t it?”8

The mention of the weapon going in “all the way up to the base of the blade” and “to the hilt” makes it clear that this is a throwing knife, not a star, because star-type shuriken don’t have hilts.

By the late 1950s the modern ‘ninja’ as we now know him had begun to take off in Japan, and by the early 60s we see movies like Yamamoto Satsuo’s surprise hit Shinobi no mono (1962) that feature unmistakable ‘ninja’ using the star-type shuriken we all know and love.9 From this point onward, accounts of shuriken are likely to reflect the influence of this newly-popularized ‘ninja’ lore, so they’re of little value to our discussion here.

Now, the texts surveyed above are quite a mix, comprising history, folklore, and outright fiction. Bearing in mind our warning from last time about not being misled by depictions of weapons in pictorial art and fictional texts, a critical reader might point out that showing shuriken in detective fiction might give us a sense for what the general understanding of the term shuriken was, but - what about some evidence that shuriken throwing-knives were actually used in real-world Japan?

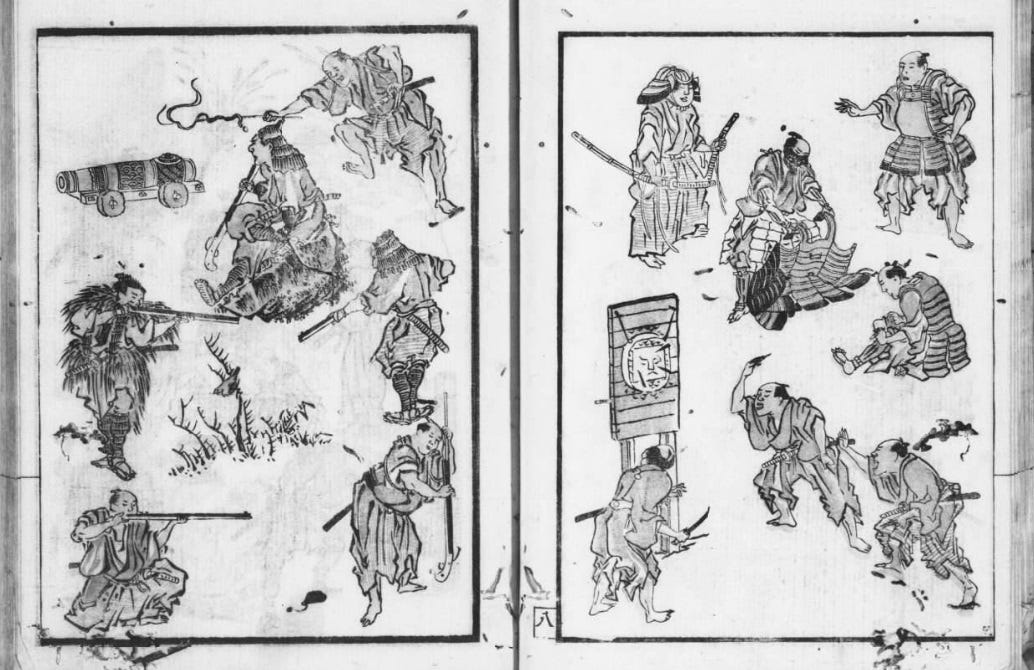

I’m not sure whether we can definitively state that throwing-knives were regularly used in life-or-death situations in Japan, but I think it’s likely that they were at least a training weapon in early modern martial arts. The image at the top of the page with the guys in the bottom-right throwing knives at a target, for instance, seems to suggest that knife-throwing may have been part of Edo-era warrior training in general. Elsewhere in the picture you see other guys practicing with muskets or putting on armor, and the guys throwing the knives are all wearing swords, which marks them as members of the Edo-era warrior class.10

But let’s keep the discussion focused on our main topic of the historical shinobi and sum up what we’ve found:

The word shuriken definitely can be found in texts predating the idea of the modern ‘ninja’. However:

As far as can be determined, it almost never refers to star-shaped throwing weapons. Rather, it seems to denote the throwing of a straight blade, whether designed for that purpose or not.

It’s probable that the word shuriken also came to be used by extension as a kind of shorthand word for a throwing-knife.

There is never any suggestion in any of the texts surveyed that shinobi routinely used or specialized in shuriken, whether star-type or knife-type, or that the weapon was associated with them. In fact, knife-type shuriken seem to have been a generally available and widely-known weapon that almost anyone could use.

All of this, of course, raises one giant question: if shuriken weren’t throwing stars and they had no connection to shinobi, then where did the idea of star-shaped shuriken as the classic ‘ninja’ weapon come from?

That, dear reader, is what we’ll look at in the next post.

I should qualify this by noting that Stephen Turnbull suggests in his 2017 Unmasking the Myth that a few star-shaped shuriken do appear to have existed (see Turnbull, Ninja: Unmasking the Myth, pp. 168-69). However, these were probably novelty or display items, and as we’ll see below, there’s no evidence that they were ever actually used, or that they were what most people in Japan understood by ‘shuriken.’

Yuasa Jōzan 湯浅常山 (1708-1781), Jōzan kidan 常山紀談 (Hakubunkan, 1909), p. 704. Japanese text: 馬より突き落とされしが、脇差を抜いて手裏剣に打つ、井上が弓手の股に中る. You can read the text for yourself courtesy of the National Diet Library here.

Sanmon gosan no kiri 樓門五山桐. Kabuki play titles are weird and often don’t seem to match the ‘normal’ readings of the graphs, so don’t worry if you’re studying Japanese and couldn’t figure out the reading. I can’t half the time either.

James Curtis Hepburn (1815-1911), A Japanese-English and English-Japanese Dictionary (Z.P. Maruya and Co, 1894), p. 598. Available through Google Books here. Hepburn was the dude who came up with the system of romanization for Japanese that most of us outside of Japan use today, by the way.

Miki Takeji 三木竹二 (1867-1908). Text and full citations can be found at the wonderfully useful Aozora Bunko. To save time, I’ve used the Aozora Bunko text for several of the below examples.

Yanagida Kunio 柳田国男 (1875-1962), Yama no jinsei 山の人生 (first pub. 1925). Text from Aozora: 同君の祖父某、四十年ばかり以前に、山に入って不思議な老人に行逢うたことがある。白髪にして腰から上は裸、腰には帆布(ほぬの)のような物を巻きつけていた。にこにこと笑いながら此方を向いて歩んでくる様子が、いかにも普通の人間とは思われぬ故に、かねて用心のために背に負う手裏剣(しゅりけん)用の小さい刀の柄(つか)に手を掛け、近く来ると打つぞと大きな声でどなったが、

George Cameron Stone (1859-1935), A Glossary - you know what, I’m not writing that out again. Just A Glossary (Southworth Press, 1934), p. 564.

Sakaguchi Ango 坂口安吾 (1906-1955), Meiji kaika Ango torimonochō 明治開化 安吾捕物帖 (First serialized 1950). Text available through Aozora here. Japanese text is: 新十郎は死体をしらべた。五兵衛の脾腹(ひばら)に突きささっている一本の小柄(こづか)。手裏剣に用いるものだ。刃の根元まで突きこんでいるが出血は少い。and 「手裏剣が柄の根元までブスリ突き刺すものか、ということさ。人の腹はやわらかいが、豆腐にくらべてはチトかたいなア」

Yamamoto Satsuo 山本薩夫 (1910-1983), dir., Shinobi no mono 忍びの者 (Daiei, 1962). Believe me, I will have a LOT to say about Shinobi no mono going forward.

I must credit Stephen Turnbull for giving the provenance of this image in his 2017 Unmasking the Myth. The image had previously appeared in cropped form and without any provenance, described simply as an “old book illustration,” on p. 17 of his 2003 Ninja: AD 1460-1650, and I had been trying to track it down for a few years without success. I’ll say more about Turnbull’s 2003 use of the image in the next post or two, when I’ll cover the unfounded claims made about shuriken by modern ‘ninja’ historians.