The existence of this Substack notwithstanding, I am not really a full-time scholar of ‘ninja’ nonsense. Covering this stuff is a relatively recent development in my academic career; before that, I published a book on Japanese poetry in the late 19th century, as well as a number of articles discussing the uses of literary Chinese in Japan (a topic I’ll expand on a bit below) and intellectual exchange between Japan and China.

Before a general lack of moral fiber led me into writing about ‘ninja’ a few years back, my main scholarly project was a translation of a gigantic 19th century history of Japan entitled An Unofficial History of Japan (in Japanese, Nihon gaishi).1 The Gaishi, as I’ll refer to it, is essentially a history of the rise of the samurai in medieval Japan. It was written by a scholar, poet, and man of letters named Rai San’yō, and completed in 1827.2 The text itself begins by covering the rebellion of the warrior Taira no Masakado in eastern Japan in 939-940, and more or less ends seven hundred years later with the supremacy of the house of Tokugawa at the end of the Warring States period in the early 1600s.3 Along the way the Gaishi covers almost all of the major warrior houses of Japanese history, such as the Taira, Minamoto, Hōjō, and Ashikaga; the notable Warring States clans Mōri, Takeda, Uesugi, and Later Hōjō; and then the three great unifying houses of Oda, Toyotomi, and Tokugawa.

I started translating the Gaishi in the autumn of 2016, and the project is only now approaching completion. As of right now I basically divide my research time between working on the Gaishi and writing the ‘ninja’ stuff, but the two projects do in fact intersect in some some surprising ways, so what I want to do in this and the next few posts is first to introduce the Nihon gaishi itself, then to give some examples of how it’s potentially useful in thinking about the ‘ninja’ issue, or at least the issue of unconventional warfare in medieval Japan.

Nihon Gaishi: Kind of a Big Deal

The first thing to know about the Gaishi is that it was huge, in a variety of senses. Its 700+ years of Japanese history fills twenty-two volumes in the original, and the complete English translation is going to weigh in at about 750,000 words (seven hundred and fifty thousand - that wasn’t a typo). For comparison, a standard academic book in English these days is maybe 90-100,000 words and 220-odd pages. The point is that Nihon gaishi is gigantic, and this is a large part of the reason why it’s taken me almost ten years to even near completion.

Nihon gaishi was also huge in terms of reception and popularity. Between about 1844 and 1900, almost everyone in Japan who could read the Gaishi did - which is to say, almost every reasonably literate man and quite a few women. The Japanese scholar Andō Hideo has estimated that during the period in question the Gaishi sold somewhere between 300-400,000 copies, which would be pretty impressive in 2025 but which is absolutely stunning by late 19th century standards.4 The number of people the text actually reached would be several times that 300-400K figure, by the way, because we’d have to account for lending libraries, resale, or for the reasonably common practice in Japan of reading books aloud to a group as a social activity (rather than silent reading, which is now the default). There’s also plenty of anecdotal evidence from publishers, educators, scholars, and Western visitors to Japan to support the claims for its ubiquity. Basically, the Gaishi was a 19th century blockbuster.5

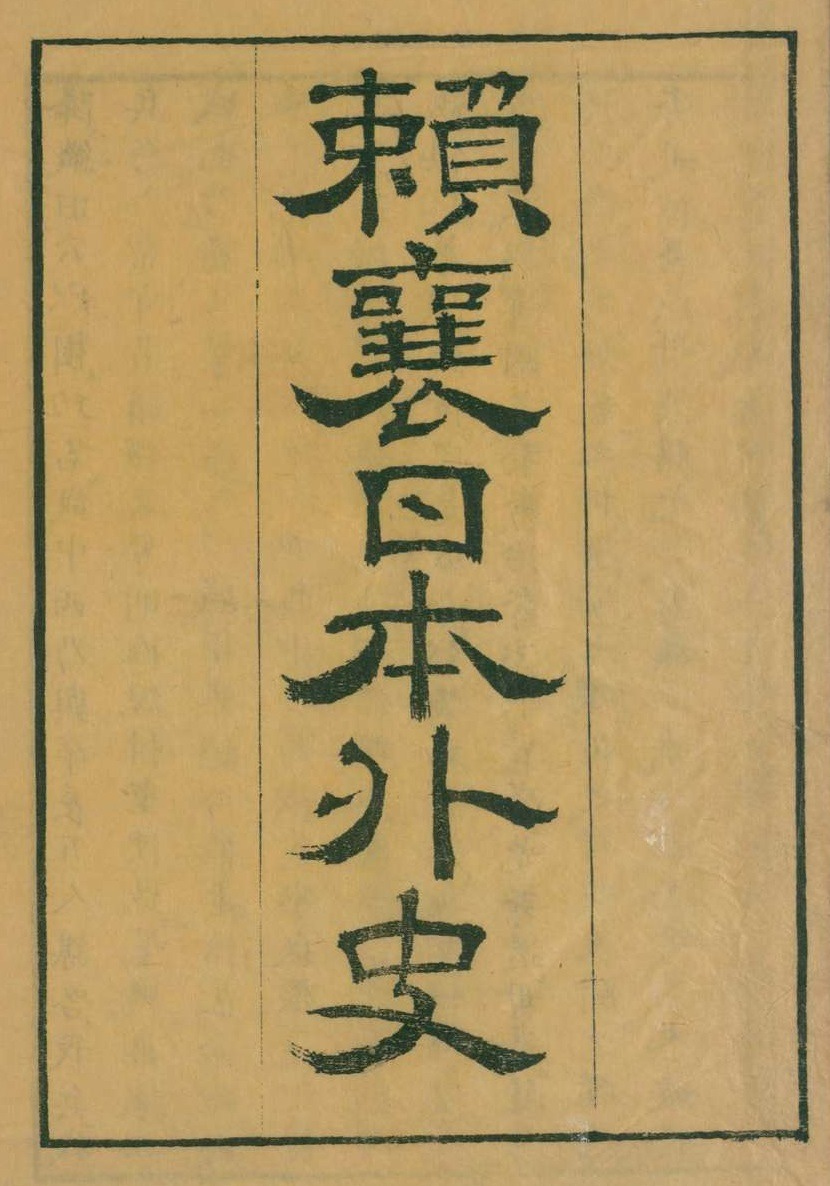

All of this raises the question, then - why has it not previously been translated, if it’s such a big deal? Well, there’s a few things going on here. One is that, as noted above, it’s really big, and not everyone wants to take on a long-term project of that size. Another is that the Gaishi isn’t written in Japanese, at least not in the strict sense. It’s written in what’s called kanbun, which is basically classical Chinese used by Japanese writers.6 Anyone with even basic knowledge of the Japanese language can tell as much by glancing at almost any page of the text, because neither of the syllabic scripts of hiragana or katakana are used at all, just kanji:

So…this is a history of Japan, written in Japan by a Japanese scholar, but he didn’t actually write it in Japanese? Yes, exactly, and if you’re a bit confused by that, you’re not alone: the early 20th century Japanese linguist Haga Yaichi recalls finding, to his considerable annoyance, that a copy of Nihon gaishi had been shelved under “Chinese Literature” in what was then the Royal Library in Berlin.7

In actual fact, though, using kanbun was not all that unusual for serious formal writing across much of Japanese history. The easiest way to explain this is to say that kanbun held a status in Japan very similar to that of Latin in medieval Europe, as a prestigious language of scholarship and intellectual activity. So there wasn’t anything particularly odd or surprising about Rai San’yō’s choice of kanbun, because history was a serious intellectual activity, and quite a few other contemporary histories of Japan, such as the even more gargantuan Great History of Japan (Dai Nihonshi) were written in kanbun too.8 This choice was more than purely linguistic, since in the mind of Rai San’yō and other historians like him, writing in kanbun made their histories a continuation of a much larger tradition of famous histories in East Asia, notably the legendary Chinese chronicles Records of the Grand Historian (Shi ji) and Zuo Tradition (Zuo zhuan).9

Practically speaking, the fact that the Gaishi is in kanbun would in time prove a bit of an obstacle to its being translated, because until about twenty years ago it was relatively unusual for scholars of Japanese literature to also be trained in reading kanbun and/or classical Chinese. The field shifted, though - nowadays almost every PhD student in Japanese studies is expected to be proficient in at least one additional Asian language, so kanbun works have seen a lot more focus in the last few years, which is all to the good.

The last reason why the Gaishi hasn’t previously been translated, and also why you’ve most likely never heard of it, is that it was fairly comprehensively pushed out of the picture after the Pacific War. I did a survey of published editions of the Gaishi a few years back, and found that while there had been over a hundred editions published between 1844 and 1945, since 1945 there’s been a grand total of three. It also isn’t included, even in excerpt, in any of the many authoritative anthology editions of classical Japanese literature published in Japan during the postwar period.10

There are probably a few reasons for this de-canonization, but I think the main one is pretty simple: the Gaishi is primarily about war, and that was not what postwar Japan wanted to be about. It wanted to be about peace, progress, and technology, and so tales of samurai proclaiming their undying loyalty to the Emperor before going off to hack people’s heads off in blood-soaked combat were, frankly, a bit embarrassing. There’s an interesting comparison to be had here with Japan’s major contribution to world literature, the Tale of Genji. Like the Gaishi, the Tale of Genji was widely used in wartime Japanese propaganda, but the Genji suffered no particular change in status after the Pacific War; in fact, it remains probably the representative work of Japanese classical literature to the present day.

Coming Soon to a Bookstore Near You

I’ve wanted to translate Nihon gaishi ever since I first came across it in a kanbun seminar in grad school in 2008, and you know what, the cool thing about my job is that I actually get to do these kinds of passion projects and get paid for them.

If I can digress for a moment here, the bit of Nihon gaishi that got me hooked was a very famous exchange in Book Eleven between the two warlords Takeda Shingen and Uesugi Kenshin, in most respects deadly rivals in central Japan:

Shingen’s domains had no coastline, so they relied on a supply of salt from the Tōkaidō region, the eastern and southern coastline of Honshū. The rival warlords Imagawa Ujizane and Hōjō Ujiyasu then conspired to secretly cut off the supply of salt, causing great consternation in the province of Kai.

Salt was needed to preserve food, and the lack of it could have resulted in starvation in Shingen’s domains, especially given the long winters in the mountains.

When Uesugi Kenshin learned of this, he sent a letter to Shingen, which said, “I hear that Ujiyasu and Ujizane seek to use salt to inconvenience you. Cowardly and unrighteous! I may be your rival, my lord, but our rivalry is of the battlefield, not of the store-cupboard. I ask that from now on you supply yourself with salt from my domain; take as much or as little as you may wish.” And he gave orders to the merchants of his domains to supply Shingen at a fair price.11

This is a well-known example of supposed honor among fellow samurai; Nitobe Inazō included it in his widely-misinterpreted book Bushido, for instance.12 Given this passage to translate in our 2008 seminar, I, of course, screwed up, interpreting the verb 仰 (which should be ‘supply’ or ‘obtain’) to mean “worship,” so I had the people of Shingen’s domains “worshipping salt.”13

So, obviously, that left me with a point to prove to the rest of the seminar, and…well, here we are.

Anyway, the translation proper is basically done as of October 2024, though there’s still a fair bit of work remaining on annotation, making maps, checking personal names, and so on. The one stumbling block in academic publishing would normally have been finding a publisher willing to take on the entire project - it is, as I have noted, huge - but luckily, we don’t have to worry about that, because the translation is currently under contract with Oxford University Press’s Hsu-Tang Library of Classical Chinese Literature. It’s expected to comprise four full volumes of around 450 pages each, and I’m hopeful it will begin to appear by the end of 2027. I’d like to think that, once published, the translation will be useful to anyone wanting a primary source work covering the samurai era and the Warring States period in particular.14 To be honest, there really aren’t that many primary sources covering the Warring States period available in English; for all that the ‘ninja’ guys are really into, say, the chronicle of the Takeda clan The Military Annals of Kai (Kōyō gunkan, c. 1616), it still isn’t available in English translation.

On the topic of sources, then, I want to note that one of the quirky things about Nihon gaishi itself is how San’yō went about writing it. Its contents are drawn from a very wide variety of Japanese historical chronicles, and a lot of the time San’yō reproduces the original content in close paraphrase or even verbatim. San’yō’s use of the late 14th century Chronicle of Great Peace (Taiheiki) in Books Seven through Nine of the Gaishi, for instance, is so close to the original that Andō Hideo, quoted above, describes this part of Nihon gaishi as basically a “re-dubbing” of Taiheiki into kanbun.15

This sort of thing would be probably be considered inappropriate use of sources nowadays, but the rules were different in Tokugawa Japan. More importantly, it means that Nihon gaishi provides us with more or less proxy access to a very wide range of interesting and useful Japanese historical documents. And that, to bring us back to talking about the ‘ninja’ stuff, is very useful indeed, because what Nihon gaishi is therefore doing is synthesizing all of these sources into a kind of panoramic picture of a lot of aspects of medieval warfare. It’s a little bit like a treasure map, in that it’s very often possible when reading Nihon gaishi to identify the original source that San’yō himself was using. Such sources often contain interesting descriptions of both conventional and unconventional warfare in the medieval period, and the advantage of that is that it allows us to put together a picture, based mostly on primary sources, of how spying, assassination, sabotage - all the things the ‘ninja’ are supposed to have done - actually worked in medieval Japan.

So, that’s what we’ll start to do in the next post. I’d like to showcase how useful the Gaishi can be in terms of the ‘treasure map’ function I’ve just described, so what we’ll do is to focus on an episode of military espionage from Book 10 of Nihon gaishi, involving warriors from the rival Later Hōjō and Uesugi clans in eastern Japan.

Nihon gaishi 日本外史. Literally an ‘outside’ history, hence the translation of ‘unofficial.’

Rai San’yō 頼山陽 (1780-1832).

Taira no Masakado 平将門 (?-940). I say “more or less” because technically the last chapter covers the Tokugawa Shoguns all the way up to San’yō’s own lifetime (late 18th/early 19th century). There’s very little detail on any of the more recent Shoguns, though, probably because San’yō didn’t want to run the risk of pissing off some extremely powerful people.

Andō Hideo 安藤英男, Rai San’yō Nihon gaishi 頼山陽日本外史 (Kondō Shuppansha, 1982), p. 1.

If anyone’s interested I wrote an academic article about the Gaishi a couple of years ago, mostly focused on its worldwide reception during the late 19th century but also with plenty of general detail: Robert Tuck, “Nihon Gaishi Goes Global: A Translation History of a Nineteenth-Century Blockbuster” Monumenta Nipponica 76-1 (2021).

Kanbun 漢文, literally ‘the writing of Han China.’ It’s normally translated as “literary Sinitic” these days, for reasons I won’t go into here. It isn’t quite the same thing as standard classical Chinese as used in China proper - there are some unusual or unique elements to Japanese kanbun - but for our purposes today we don’t really need to make the distinction.

Haga Yaichi 芳賀矢一 (1867-1927).

Dai Nihonshi 大日本史. This history was presented to the Tokugawa bakufu in 1720, but work continued on it until the 20th century. Dai Nihonshi is so comically enormous - more than 400 volumes - that I suspect it will never be translated, but you never know.

The two ancient Chinese historical chronicles Shi ji 史記 (‘Records of the Grand Historian’; ca. 91 BCE), by Sima Qian 司馬遷 (ca. 145–ca. 86 BCE), and Zuo zhuan 左伝 (‘Zuo Commentary;’ late fourth century BCE) are the absolute grand-daddies of basically all premodern history writing in East Asia. They’re incredibly famous and served as models for both historians and prose stylists for, like, 1500+ years. Their influence on San’yō’s Gaishi is considerable, too.

Yes, I’m citing myself: Tuck, “Nihon gaishi Goes Global,” p. 107.

Kanbun: 信玄國不濱海。仰鹽於東海。氏真與北條氏康謀。陰閉其鹽。甲斐大困。謙信聞之。寄書信玄曰。聞氏康氏真困君以鹽。不勇不義。我與公爭。所爭。在弓箭。不在米鹽。請自今以往。取鹽於我國。多寡唯命。乃命賈人平價給之。

Nitobe Inazō 新渡戸稲造 (1862-1933). If you’re interested in how and why Nitobe’s book has generally been misinterpreted, I recommend allowing G. Cameron Hurst III to yell at you for about 20 minutes in his article “Death, Honor, and Loyalty: The Bushidō Ideal” Philosophy East and West vol. 40 no. 4 (October 1990).

In my defense it usually does mean that, at least in modern Japanese. We were all young and stupid once…

Given my point about San’yō’s historical approach below, though, it’s kind of debatable whether the Gaishi is really a primary source in the strict sense. It’s arguably more a compilation of paraphrased primary sources. Kind of a 1.5 source, maybe?

Andō, Rai San’yō Nihon gaishi, p. 14.

Exciting (and impressive) project indeed, something like this I'd probably pre-order if/when possible!