If there’s one thing that everyone knows about ‘ninja,’ it’s that they were assassins. They killed people, in other words. High-status people, such as warlords, Shoguns, or the equivalent, whose deaths would be politically significant and who would be heavily guarded. So not only did ‘ninja’ kill people, they were uniquely good at it, reaching targets that no other group could be expected to deal with.

The idea that ‘ninja’ were assassins is so deeply embedded in the pop-culture image that it’s almost unnecessary to argue the point, but I’ll give a few examples anyway from the English-language pop literature. In the early 1960s, when James Bond author Ian Fleming visited Japan and encountered the notion of the ‘ninja,’ he definitely understood them to be assassins, as we see in this cartoon strip adaptation of You Only Live Twice published in the British newspaper Daily Express in 1964:

The title of the first major book on ‘ninja’ in English, Andrew Adams’ 1970 Ninja: The Invisible Assassins, speaks for itself:

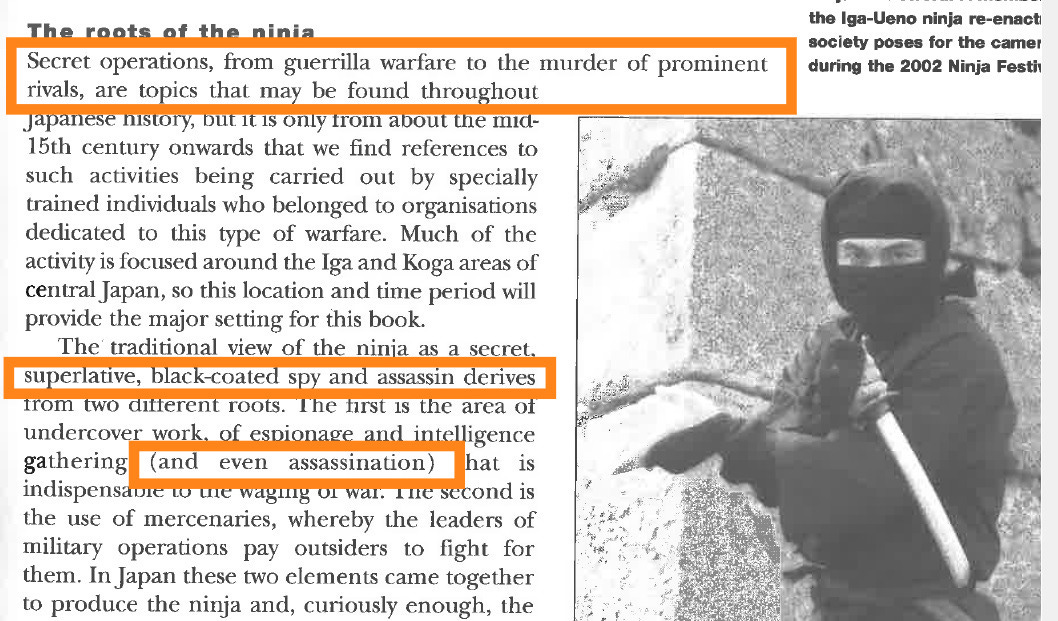

Donn Draeger’s best-selling Ninjutsu likewise contains numerous mentions of ‘ninja’ as expert killers - some of which mentions, as Draeger admitted in the book itself, he believed to be fictional. Stephen Turnbull’s widely-read books between 1991 and 2008 all contain sections on purported examples of historical ‘ninja’ assassination attempts, too:

It wasn’t just the English-speaking guys, of course - both the martial arts master Hatsumi Masaaki and the alleged ‘historian’ Okuse Heishichirō spilled quite a bit of ink on the notion that ‘ninja’ were uniquely skilled assassins.

Guns Don’t Kill People, Ninja Kill People

So is there any hard evidence to support this idea? Did clans of trained assassins regularly kill high-status people in medieval Japan?

Uh, no. Doesn’t look like it, anyway. As far as I can tell, in all of Japanese history there doesn’t appear to be a single verifiable case of a successful assassination carried out by a figure we can clearly show to be a ‘ninja’ in the usual sense of the word.

The “assassins” claim is very difficult terrain for ‘ninja’ history, because by definition assassination produces an obvious end product. When someone as prominent as a warlord dies, people tend to notice, and they generally record it. This means that we know when most major warlords died, often to the precise day, and usually we also have a pretty good idea how they died. Right from the start, a discipline as flaky as ‘ninja’ history is going to have trouble with this, because it means that claims of assassination will be easy to verify. No death, no assassination.

This, I think, is why so many claimed ‘ninja assassinations’ fail to kill their target, but that’s a point I’ll explore in a subsequent post. A good starting point for now is to look at some verifiable examples of assassinations in Japanese history, and see if we can find any patterns, or if any of them seem like they fit with the ‘ninja’ idea. What we might expect, if we grew up on the pop-culture version of the ‘ninja,’ would be cases of lone assassins sneaking into heavily guarded castles by night, dispatching their hapless victims by blade or poison, and making their escape before anyone could sound the alarm.

What Part of Noh Don’t You Understand?

So let’s get one thing out of the way - people were assassinated in medieval Japan all the damn time. It absolutely was an occupational hazard for any reasonably high-status warrior, and many warlords, especially in the turbulent Warring States period (1467-1600), were justifiably paranoid about the possibility.

But one major pattern in historical assassinations in Japan is that you were just as likely to be assassinated by your own guys as you were by someone from outside. Let us ditch once and for all the image of the ‘loyal samurai,’ because betrayal and literal backstabbing were extremely common. So many warriors were murdered by men they had trusted that again, it seems almost unnecessary to give examples, but let’s do so anyway. For convenience, I’m drawing the textual evidence here from the late 18th and early 19th century scholar Rai San’yō’s Nihon gaishi, a massive late-Edo period history of Japan I’m in the process of translating.1

A lot of the time, the preferred method was to wait to strike until the target had made himself vulnerable, rather than forcing the issue. In 1441, for instance, the 6th Ashikaga Shogun Ashikaga Yoshinori was murdered by his vassal Akasaka Mitsusuke after the two had been on bad terms for several years.2 Mitsusuke invited the Shogun to his house to enjoy a banquet and some cultural pleasures such as a Noh performance, then ambushed and killed him:

[The Shogun] Yoshinori duly came to Mitsusuke’s residence, but he left his armed guard outside the gate, going in with only a few nobles and some of his commanders. When the festivities were at their height, the guests watched a performance of sangaku [i.e., Noh] theatre. By the time the repertoire of plays had reached the performance of the play Cormorant Fishing, it was dusk and the light was fading. There came a shout from within the residence, “The stables! The horses are going to get out!”

The gate was closed in great haste, and as soon as it had been closed, armed men poured forth. Yoshinori made to rise, but [Mitsusuke’s relatives] Noriyasu and Norisuke came forth together, grabbing his arms from either side. Pushing him down to the ground, they said, “What is about to happen today, my lord, you have brought on yourself.”

From behind a screen [Mitsusuke’s retainer] Atsumi came forth, brandishing a sword, and beheaded Yoshinori. Those in the room drew their swords and leapt to their feet, but all who did so were quickly dispatched, with several dozen killed in all.3

Rather like the infamous Red Wedding in Game of Thrones, there’s no need to sneak into the victim’s castle when you can have him come to you.

Baths Are Bad for Your Health. Here’s Why

Baths also seem to have been a popular venue for assassination, for obvious reasons. The intended victim would, if bathing, likely be alone or with only one or two attendants, and without weapons or armor.

This is what happened to the powerful warlord Hosokawa Masamoto in 1507.4 After causing chaos in his clan’s succession plans by failing to produce a biological heir and then adopting, then changing his mind about three potential other heirs, Masamoto was murdered in his bath at the behest of two of his own vassals, who hoped to thereby seize control of the Hosokawa clan for themselves:

So then [Masamoto’s vassals] Yakushiji Tomotsugu and Kōsai Mataroku bribed Masamoto’s trusted personal attendants, Fukui and Togura, to spy on him and look for an opportunity to present itself. During the sixth month of that year [1507], Masamoto was observing a ritual of purification, and went into his bath-house one evening, at which Togura went in after Masamoto and stabbed him to death. When Masamoto’s trusted attendant Hahakabe ran for help he too was stabbed, though the wound was not fatal and he escaped to Awa Province. Kōsai Mataroku and his co-conspirators thereupon welcomed [the first adopted heir] Sumiyuki to the capital from Tanba Province, and installed him as Masamoto’s heir. There was nothing the Shogun Yoshizumi could do to prevent any of this.5

So again, you really don’t need ‘ninja’ to sneak into the target’s residence when you can just bribe the guys who are already there.

Or consider another Shogunal assassination, that of the 13th Ashikaga Shogun Ashikaga Yoshiteru in 1565.6 As Nihon gaishi tells it, Yoshiteru’s vulnerability was that he had moved to a new palace and there had been some delay in getting the doors installed. Yoshiteru’s enemies thereupon sent a large force of a thousand or so men to gain entry by deception and murder Yoshiteru:

In the fourth month of the eighth year of Eiroku [1565], the Shogun Yoshiteru moved into the newly renovated Nijō residence. The doors for the building’s gate, however, had not yet been put in place, and [Yoshiteru’s enemies] the Miyoshi Triumvirate said to one another, “We cannot let this opportunity slip!”

So then in the fifth month the Triumvirate, along with [their ally] Matsunaga Hisahide and his son Yoshimichi, took command of a thousand or so of their men, giving each man a bamboo pole with an insignia flag attached to it that declared they were making a pilgrimage to the Kiyomizu-dera Temple, and moved into the capital. A further element of their plan was to strike when the Shogun was off his guard, and so they also brought with them a false petition of complaint, which they brought before Yoshiteru through the offices of Shinji Haruie, a trusted vassal of the bakufu.7

The false petition was because one of the functions of the office of Shogun was supposed to be judicial, which meant deciding lawsuits and dispensing justice. The idea here in claiming to present a petition was to sow confusion about the attackers’ intentions and delay the defenders’ response, and it works superbly. The attackers storm in, catching the defenders off guard and cutting a swathe through them. Yoshiteru does his best, but his position is hopeless:

At the last, even when every one of the warriors loyal to him had fallen in battle, Yoshiteru still fought so furiously that no rebel dared approach him. But then a rebel by the name of Ikeda leapt out from behind a door and slashed the Shogun on the leg, felling him. Gathering around him, the rebels placed a fallen shōji screen over Yoshiteru, then stabbed him to death with their spears.8

So in this case the assassination is carried out with a large conventional force, but the basic principles are the same. Wait for the target to make himself vulnerable, use deception and betrayal to get there, and then kill him.

Work Harder, Not Smarter

There are many more examples I could have used, but I think the picture is clear enough. Medieval warriors were perfectly capable of coming up with effective plans to kill their political rivals without any need to hire ‘ninja’; in fact, hiring a lone assassin to force his way into the castle past dozens of armed guards would have been doing things very much the dumb way. You simply didn’t need to do that; if you were smart, patient, and ruthless enough, you could work on the intended victim’s own vassals or wait for him to let his guard down, then send him shuffling off this mortal coil when the moment was right, all on your own initiative.

The point I’m making is that the ‘lone hired assassin’ thing doesn’t really fit with much of what we know about how assassination worked in medieval Japan. It’s a lot more dramatic to envision a black-clad figure moving silently through the night, sure, but we can see from the above examples that such a plan would have had a much higher risk of failure, and quite often there would have been no need to resort to such measures in the first place. There were usually plenty of other ways to get at the target if the would-be killer was willing to be patient and engage in a little deception. Even if ‘ninja’ assassins had been available to hire in the medieval period, it’s not clear why a rival warlord would bother to do so.

Now of course, none of the above rules out the idea that there might have been skilled assassins floating around. In fact, if you look at the pages of the best-selling English-language ‘ninja’ histories, you’re going to see breathless mentions of maybe a dozen or more supposedly real historical ‘ninja’ assassinations. What’s up with them?

Very well then. In the next post, let’s take a critical look at the ‘ninja assassinations’ that English-language authors have offered up, and see what we find.

Let me acknowledge that Nihon gaishi is not necessarily all that reliable as history; its own sources are often medieval war tales, which are themselves romanticized or embellished. I’m using it here because I personally am very familiar with it, and for convenience, because it’s got lots of tales in one easy-to-use source. If seriously challenged on this point I would argue that in broad outline its accounts of what happened (who killed whom, and how) are more or less usable to illustrate some general ideas about how assassination happened.

Ashikaga Yoshinori 足利義教 (1391-1441); Akasaka Mitsusuke 赤坂満祐 (1381-1441).

Kanbun text: 義教卽往。置隨兵于門外。獨與朝貴諸將入。置酒高會。觀散樂。樂至鵜飼。時已薄暮。第中有呼曰。廐馬逸矣。因急關門。門關而甲發。義教將起。教康教祐耦進。執其左右手。伏之曰。今日之事。公自取之。渥美自屏後出。揮刀斬其首。一座拔刀起。起者輒見殺。From Kōbunsha Editorial Committee, eds., Nihon gaishi kōgi (Kōbunsha, 1913), 2:298.

For those wondering why the above text doesn’t ‘look’ like Japanese: until the late 19th century, historical and other formal writing quite often used kanbun 漢文 (literally, ‘the writing of Han China’) which is more or less a variant form of classical Chinese. It was, I suppose, similar to the way in which educated men used Latin for a lot of serious writing in medieval and early modern Europe. Nihon gaishi was originally written in kanbun, so that’s what I’m quoting here, though over time it was often translated into classical, then modern Japanese for larger readerships.

Hosokawa Masamoto 細川政元 (1466-1507).

Kanbun text: 乃賂政元近士福井戶倉等。伺察政元。是年。六月。政元齋戒。夜入浴室。戶倉就而刄之。近士波波伯部走救。亦爲所刄。不殊。奔阿波。香西等乃迎澄之於丹波。立之。義澄不能制。Nihon gaishi kōgi 2:361.

Ashikaga Yoshiteru 足利義輝 (1536-1565).

Kanbun text: 八年。四月。義輝已徙新第。門扉未成。三黨相謂曰。時不可失也。五月。三黨與久秀及其子久通等。率千餘人。人佩一竹枝爲號。宣言詣清水寺。以入京師。又謀紓其備而逼之也。佯奉訴狀。因幕府近臣進士晴舍納之義輝。Nihon gaishi kōgi 2:380-81.

Kanbun text: 而我兵終皆死之。義輝猶奮戰。賊不敢逼。賊池田某。自扉陰跳出。刈義輝足踣之。賊堆集。仆障於其上。攢槍弒之。Nihon gaishi kōgi 2:382.

“What Part of Noh Don’t You Understand?”

Maybe that’s a common joke in Japanese history circles, but you totally caught me off guard on that 😂