Lethal AND Low-Cholesterol: The Strange Case of the "Ninja Tofu"

Exploring the "piggybacking" technique in 'ninja' history

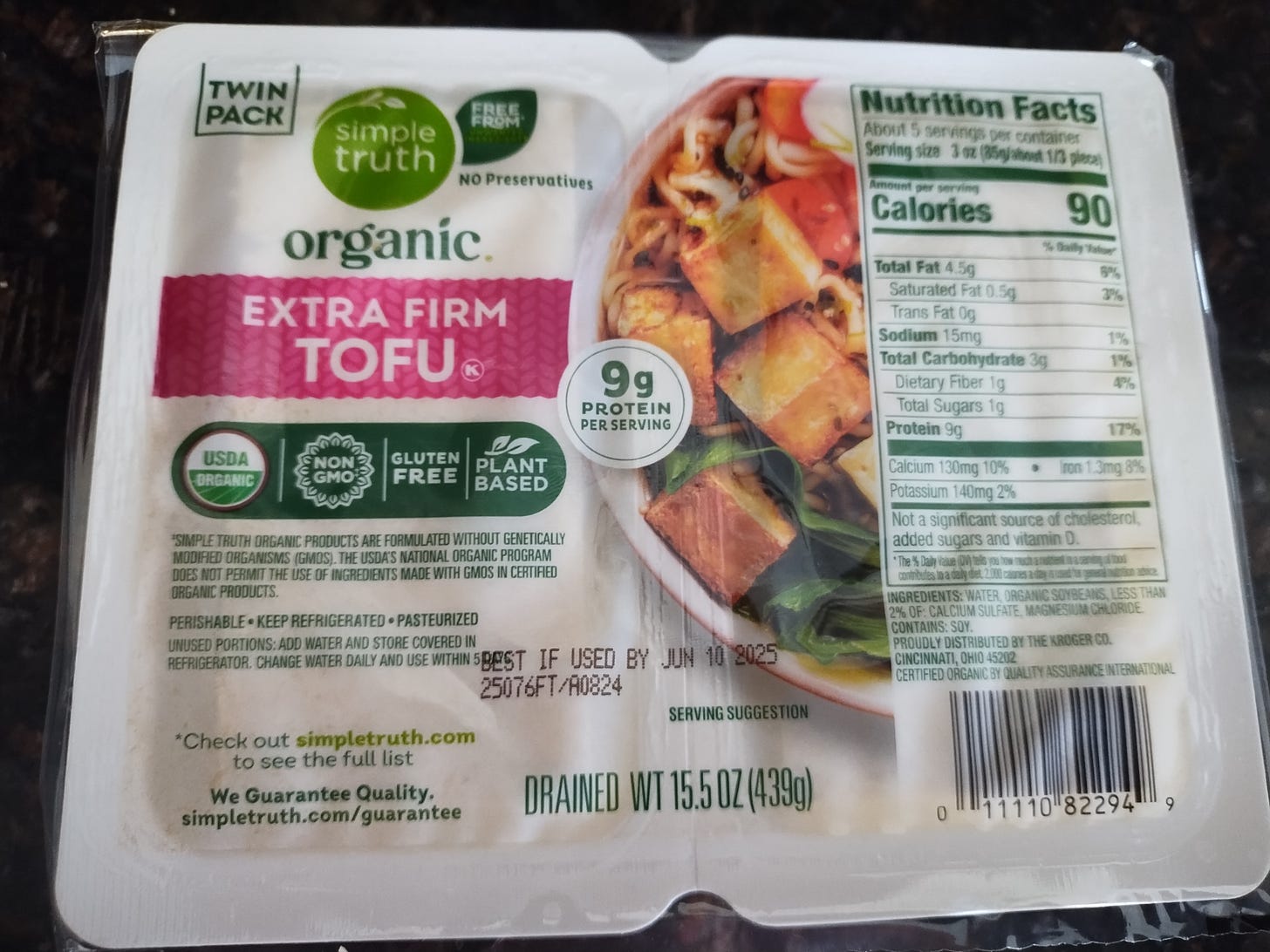

Pictured above is some tofu, also known as bean curd. Tofu is an exceedingly common foodstuff across almost all of East Asia, made from soybeans and widely admired for its health benefits, if maybe not its taste.

Pictured below is a kusari-gama or chain-sickle, a Japanese weapon consisting of a sharp sickle with a weighted chain attached to the handle. Seemingly emerging in the late medieval period, use of the kusari-gama appears to have involved tangling the enemy’s weapon with the chain while striking with the sickle blade:

So, what do the two things above have in common? Both of them, allegedly, were favorites of the historical ‘ninja.’ Or at least, that’s what you’re likely to read in the ‘ninja’ literature.

They Also Ate A Super-Secret Food Called “Rice”

The “ninja tofu” thing comes from Kuroi Hiromitsu, an author who’s written a couple of books on ‘ninja’ in English. Towards the end of Kuroi’s 2003 Secrets of the Ninja: Their Training, Tools, and Techniques, we’re given an informative lesson on the supposed diet of the ‘ninja,’ including a recipe for “tofu just like the Grand Master used to make”:

This is not a ‘ninja’ thing. It’s simply a recipe for making tofu. The same one that’s been used by basically everybody in East Asia for a couple of thousand years, which you can find today in dozens of East Asian-focused cookbooks or any number of vegan or healthy living websites. The “Other Ninja Foods” in the bottom left are also common items in the premodern Japanese diet, eaten by everyone across the country.

So, “ninja tofu,” or as the rest of us know it…“tofu.”

This certainly isn’t one of the ninja’s “secrets” - it’s not remotely secret and has nothing to do with ‘ninja’ specifically - so what’s it doing in the book?

I think there’s a couple of things going on here. One is that to an embarrassing degree, ‘ninja’ writers working in English often seem to struggle to find enough actual ‘ninja’ material to fill their books. This would explain why Donn Draeger and Stephen Turnbull (to name but two authors not entirely at random) both resorted to writing their own fiction alongside the alleged history, apparently with a view to padding out their page count. The second thing, and the one I want to focus on for the next couple of posts, is that what we’re seeing here in Kuroi’s book is the application of an historical approach I term “piggybacking,” which ‘ninja’ historians use a lot.

That Thing Over There? Totally A Ninja Tool.

“Piggybacking” works like this: You start with something in common use in premodern Japan - let’s say a wooden bucket - and then you loudly proclaim to all and sundry that yeah dude, the ‘ninja’ totally used wooden buckets all the time, they were known for it, absolutely a ‘ninja’ tool. In this way, you can invent a whole range of lore about the ‘ninja’ and their distinctive tools and weapons, and your job is made easier by the fact that wooden buckets definitely existed in premodern Japan, so you can show everyone photos of wooden buckets to support your case. The complete absence of any documented connection between the historical shinobi and wooden buckets doesn’t matter; you just have to assert it loudly and often.

Put this way, “piggybacking” is obviously ludicrous, but it’s a fundamental element in how ‘ninja’ history is written. It appears to explain basically the entirety of the association between ‘ninja’ and star-shaped shuriken, for instance. As I showed a while back, shuriken did exist in premodern Japan, though the term usually referred to straight knives rather than star-shaped weapons, and shuriken seem to have been widely used across a variety of Edo-period schools of martial arts. But as Mie University’s Yoshimaru Katsuya wrote in 2023 and his colleague Yamada Yūji confirmed in a public lecture in 2024, there’s no documented association between the historical shinobi and shuriken weapons, straight or star-shaped.1 In essence, 60s ‘ninja’ writers took a reasonably common weapon which had no connection to ‘ninja’ and built a whole range of lore on top of it, to the point where the ninja-shuriken association is about as ironclad as any you can think of.

So Kuroi’s “ninja tofu” above is useful because it’s a clear and blatant example of “piggybacking” - almost everyone in East Asia made and ate tofu, and it has no specific connection to ‘ninja.’ Hatsumi Masaaki, of Bujinkan ninjutsu fame, also does the same thing quite frequently. Let me give just a couple of examples from his 1981 English-language book Ninjutsu: History and Tradition:

What’s specifically ‘ninja’ about the matchlock pistol? I have no idea, and Hatsumi doesn’t say.2 As for the Tanegashima rifle, “used by Warring States Period ninja” - well, yes, them and just about everybody else in the late Warring States period (1467-1600). There’s zero reason to believe that these weapons had anything at all to do with ‘ninja.’

Ninja Snow Job

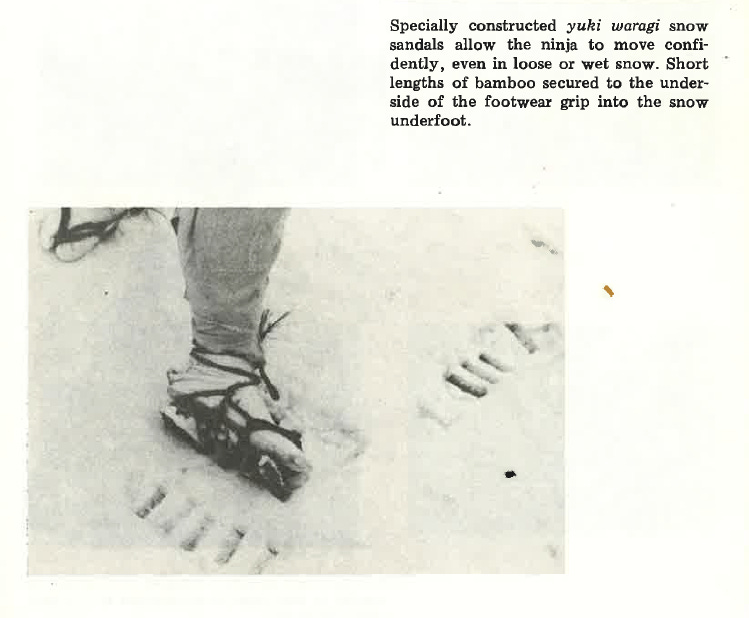

Much the same applies to Hatsumi’s account of ‘ninja’ snow gear:

OK, but…everyone in Japan used straw snow sandals. Large swathes of Japan are mountainous and quite a bit of the country, especially the western coasts of the northern regions of Japan, gets heavy snowfall in winter. To give just one example, the city of Towada in Aomori Prefecture, in the far north of the main Japanese island of Honshu, has a whole brochure on its website for an exhibition in 2019 about the history of footwear in the far north, including snow gear. The brochure is quite image-heavy, so you can look it over for yourself even if you don’t know any Japanese:

Maybe ‘ninja’ did use straw sandals to cross snow, but if so they were doing exactly what everyone else did.

No Evidence? Borrow Someone Else’s!

To frame this slightly differently, imagine you picked up a book entitled Secrets of CIA Assassins. On opening it, you learn the following nuggets of rare wisdom about these legendary killers:

They ate HAMBURGERS.

They travelled around in CARS.

They sometimes used a weapon called a GUN (picture below).

You see what I mean? Reading this, you might reasonably conclude that the author is full of shit, that he doesn’t really have much in the way of specific or unique information about the topic, so he’s padding out the pages with stuff that could apply to almost anybody in the time and society in question. In short, you learn nothing very important or useful about CIA assassins as a specific thing.

In the most charitable sense, “piggybacking” might be viewed as allowable conjecture; we know shinobi existed, so here are some things we think they might have done. Less charitably, piggybacked history is basically just fluff and padding, of the kind an undergrad might add to a paper half an hour before the deadline to try to reach the required page count. In the least charitable view, it’s a kind of intellectual hijacking - you’re taking an unrelated slice of history, sticking a ‘ninja’ label on it, and proudly proclaiming it evidence for your thesis in the hope that nobody will notice what you’ve done.

This would be one way to view what happened with shuriken, which appear to have existed as weapons in various Japanese martial arts for centuries before anyone ever thought of the idea of the ‘ninja,’ but whose history was then almost entirely subsumed by the ‘ninja’ mythos as it blew up from the 1960s onward. And as we’ll explore next, it’s also what seems to have happened with the kusari-gama chain-sickle. This distinctive weapon appears to have been its own thing in Japanese martial arts for perhaps four hundred years until it was ‘claimed’ by ninja historians in the 1960s. So, in the next post or two, we’ll take a dive into the evidence regarding the kusari-gama, and see what we can find out about it.

Yoshimaru Katsuya, “Shuriken to ninja [Shuriken and Ninja]” in Ninja to wa nani ka [What is a Ninja?] (Kadokawa Sensho, 2023), p. 330-31: “Shuriken were never weapons of the shinobi at all; the idea that ninja used them comes about through works of fiction.” (Japanese: 手裏剣はもともと忍びの武器ですらなく、創作を通して忍者が使うようになった.)

It might be worth noting that ‘60s ninja ‘historian’ Okuse Heishichirō called bullshit on the pistol thing in 1964, writing that matchlock pistols did not exist in Japan until after the Warring States period (Okuse, Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei (Shinjinbutsu Oraisha, 1999; first pub. 1964), p. 254), so the idea of this as a “ninja pistol” is anachronistic. I don’t know enough about the history of Japanese firearms to say whether he’s right or not, but if he is that would simply reinforce my point about “piggybacking.”

Yeah, right. Next you’ll try to tell us “ninja motorcycles” are just plain old Kawasakis 🙄

Seriously though, this is what I love about substack…when I clicked on the title, I legit thought it was from one of the cardiologists I follow 😂