'Ninja vs. Samurai': Vibe-Based History From About 1963

Time to put this one to bed once and for all

To put it as simply as possible, the ‘ninja vs. samurai’ thing is a product of the zeitgeist of early 1960s Japan. It has little or no support from Japanese historical sources, which is why none of the authors we’ve been looking at - Draeger, Adams, Hatsumi, Okuse - support their claims with documentary historical evidence. The one author to attempt to do this, to reconcile ‘ninja vs. samurai’ with accounts of medieval warfare, was Stephen Turnbull, and as we saw a few posts ago, the result was a conceptual mess.

Vibing with the Ninja

Because its basis in documentary evidence is so tenuous, ‘ninja’ history is extremely flexible; it can be re-invented and manipulated more or less as an individual author wishes. In that sense it’s much closer to literary creation than history, a gonzo form of fan fiction that allows for the author to work through their own particular pet themes using the extended universe that is medieval Japan. This was what we saw with the left-wing politics of the ‘ninja’ authors Shirato Sanpei and Murayama Tomoyoshi, both of whom used their ‘ninja’ works to present medieval Japan as they thought it was (or maybe should have been).

So if ‘ninja vs. samurai’ is a product of the anti-authority vibe of the early 1960s, of the Anpo riots and a general sense of a culture rising up against the man, we’d expect that ‘ninja’ claims before the early 1960s wouldn’t feature the ‘ninja vs. samurai’ thing very much, or even at all. This is indeed what we find; the two most notable prewar ‘ninja’ writers, Itō Gingetsu and Fujita Seiko, don’t seem to mention the idea. Rather, they seem to have understood what they called ninjutsusha as being simply a part of most warlords’ overall military structure, rather than despised outcasts or specially trained peasants.

The ‘ninja-samurai’ thing isn’t obviously there in the handful of ‘ninja’ materials available after the war but before the release of Shinobi no mono in 1962, either. This one-page 1957 article, from from the English-language Japan Magazine, says nothing about ‘ninja’ being opposed to samurai:

Nor does Hatsumi Masaaki’s big debut, a splashy photo-shoot in the US pulp magazine Argosy in 1961:

Nor does an article by Donn Draeger in the magazine This is Japan in September 1961, which I believe James Bond author Ian Fleming read and which inspired parts of Fleming’s 1964 novel You Only Live Twice:

The sentry struggled helplessly, almost silently, unable to cry out in alarm - he was a victim of the dreaded ninja.

Feudal Japan was full of such incidents, when violence and mayhem, systematically and scientifically operated, played a bloody role in the political events then shaping Japan’s colorful history. Rival political leaders trained and used a small, select group of spies called ninja (“stealers-in”) to obtain intelligence about the enemy and to perform other acts of espionage or violence.1

Note that a little over a year before the cinematic release of Shinobi no mono, Draeger’s understanding of ‘ninja’ appears to be substantially the same as the prewar writers Gingetsu and Seiko, in that ‘ninja’ are here seen as part of the larger military structure of feudal warlords, not as independent peasant clans or families despised by the socially superior samurai.

Jay Gluck Goes Out on a Limb

A further interesting example of how ‘60s vibes conditioned views of the ‘ninja’ comes from martial arts writer Jay Gluck. Gluck was a fascinating character - seriously, read his Wikipedia page - who wrote extensively on a whole range of topics relating to Asian and Middle Eastern art and culture. He was, it appears, in Japan during the early 1960s, right as the ‘ninja’ thing was blowing up, and like a lot of Americans in Japan during that time became very interested in the whole martial-arts-as-mystical-Asian-wisdom thing.

The concrete result of this was his 1962 book Zen Combat and the Secret Power Called Ki, a survey of lots of different Asian martial arts and philosophical thought. It contains a short section on the ‘ninja,’ as you might expect, and that section contains a claim about ‘ninja’ that, if you know anything about modern Japanese history, is really quite explosive:

Most ninja specialists were eta, or untouchables, but many samurai, or warrior class, were adept at the tricks of ninjutsu.2

In this one line, we can almost see the idea of ‘ninja’ morphing between its pre- and post-Shinobi no mono forms. The second half acknowledges that many samurai were adept at ninjutsu (Gingetsu et al’s version), but the first half is the version we’re more immediately familiar with, the suggestion that there was significant social differentiation between ‘ninja’ and other people in medieval Japan.

Actually, “significant social differentiation” doesn’t begin to cover it, because the claim that ‘ninja’ were eta is…wow.

Let me explain why Gluck’s claim is so remarkable, especially in the context of the 1960s. The term eta is an historical one meaning literally “full of filth,” and is now considered extremely offensive. It was used to refer to what Gluck terms “untouchables,” the group now known in Japan as Burakumin (literally, ‘hamlet people’).3 Burakumin are the descendants of outcast groups whose ancestors performed various jobs considered polluting or unclean, like butchery, grave-digging, leather-working, and so on during the Edo period (1600-1867). Though outcasts, Burakumin people did at least have an economic niche in that they performed socially necessary tasks. When the Meiji period (1867-1912) came, however, the social system that gave them their niche was done away with, but the prejudice against them didn’t disappear. Well into the 20th century it was not unheard of for businesses or potential marriage partners to do background checks and hire private detectives to make sure that someone was not from a Burakumin background.

What makes Gluck’s claim so potentially explosive is that the early 1960s were precisely the point at which Burakumin civil rights groups had begun to mobilize to protest discriminatory treatment in Japan. One year after Gluck’s book, in fact, there would be a high-profile legal case, the Sayama Incident of 1963, which involved a Burakumin man convicted, on flimsy evidence, of the rape and murder of a teenage girl. The conviction was widely believed to have been down to the accused’s Burakumin status, and it became something of a cause célèbre for the Burakumin Liberation League and other allied organizations.

So Gluck’s claim that most ninja were Burakumin, though casually tossed out there in Zen Combat, was potentially explosive in ways that Gluck himself may or may not have realized. I’m curious to know where he got this idea from, though again, since Gluck passed away in 2000 we’ll probably never know. Perhaps Gluck was aware of the broader Burakumin civil rights movement in the ‘60s in Japan and put two and two together in his own mind, or perhaps someone in Japan very quietly suggested it to him - I can’t imagine Okuse or Hatsumi making that claim themselves.

Needless to say, Gluck gives no evidence to support his assertion, and I am not aware of any credible evidence suggesting that the historical shinobi had any specific Burakumin connections.

Ninja History After Shinobi no mono

If we check back in on the usual suspects a couple of years later, in 1964, we find that ‘ninja vs. samurai’ does seem to be on the way to becoming a standard trope. In his 1964 children’s book Ninja and Ninja Skills Illustrated, for instance, Hatsumi Masaaki writes that:

Ninja were low-status (iyashii), and the arts of the ninja (ninpō) were considered to be skills for cowards, so ninja were not treated as fully human.4

In his 1980 Ninjutsu: History and Tradition, published in English, Hatsumi likewise writes:

Ninjutsu developed as a highly illegal counter culture to the ruling samurai elite, and for this reason alone, the origins of the art were shrouded by centuries of mystery, concealment, and deliberate confusion of history…5

It’s clear that Hatsumi wants to differentiate ninjutsu from samurai warfare somehow here, but the idea that ninjutsu was “highly illegal” makes little sense - illegal under which laws, and of which period? Were there, like, convictions for second-degree ninjutsu or something?

Okuse Heishichirō also got in on the act in 1964, writing in his widely-read book Ninja Arts: Secret Teachings and Real Examples that the one of the supposed ‘ninja’ commandments was “to endure shame in carrying out his mission.” Of this, Okuse remarks that “it is fascinating that this exhorts the ninja to reject the Bushido-like conscience” of, one assumes, the samurai.6 I have no idea where Okuse got these supposed ‘ninja commandments’ - he gives no source, naturally - but this claim also makes little sense as a matter of history, not least because Bushido itself is mostly a 20th-century invention.

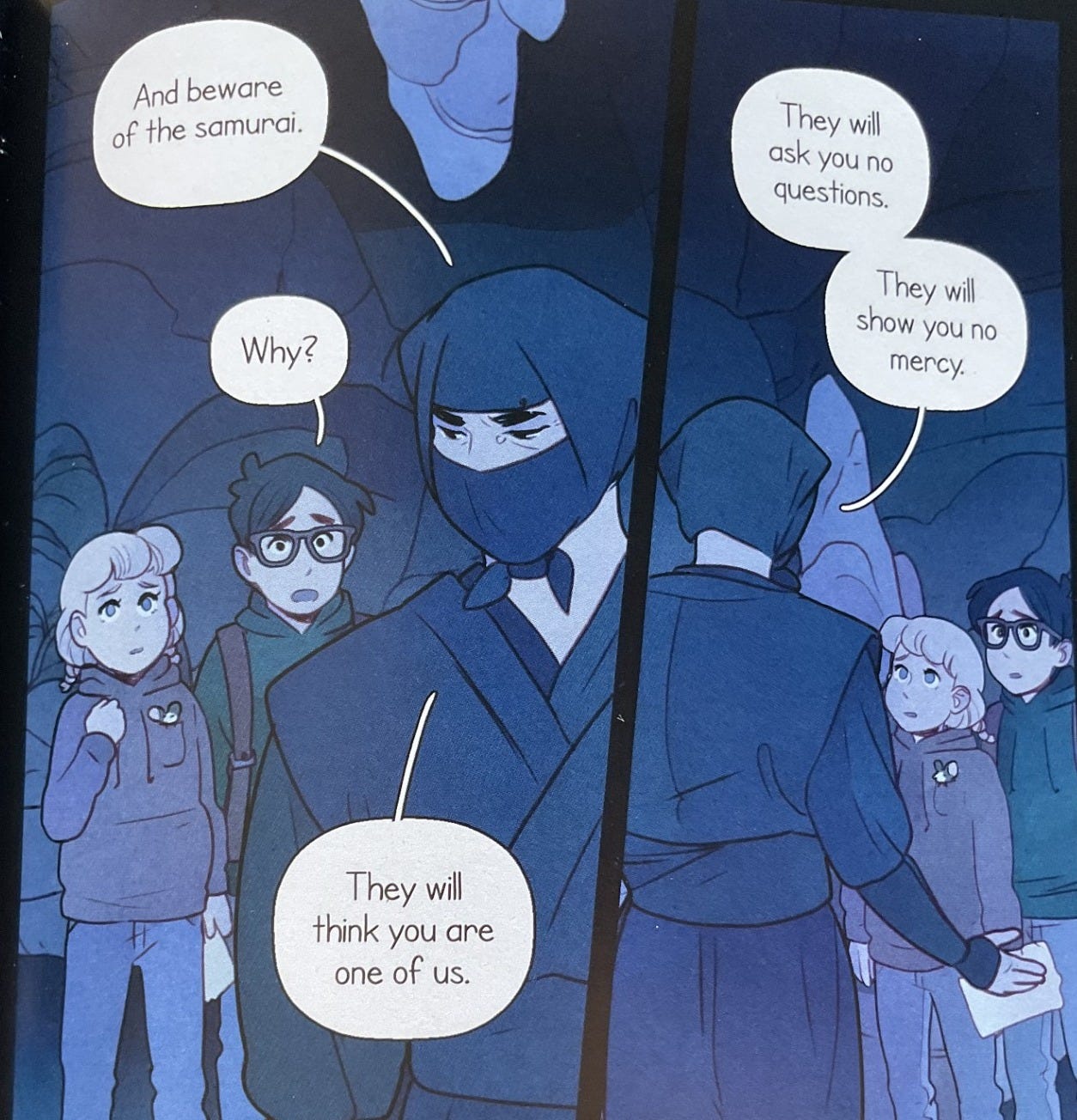

Funnily enough something similar to this idea of ninja rejecting the samurai’s sense of shame is voiced in Shinobi no mono by the Koga ninja master Fujibayashi (who is, of course, also secretly working as the master of the Iga clan):

So it looks very much as if something changed between about 1961 and 1964 in Japan, something that changed the discourse on who and what ‘ninja’ were. I strongly suspect that that ‘something’ was in fact the film Shinobi no mono, or at least a combination of the Anpo riots, Shinobi no mono, and Shirato Sanpei’s manga Ninja: The Arts of War. In other words, the cultural vibes of early ‘60s Japan shifted, and that prompted ‘ninja’ writers to adopt the fictional premises of works like Shinobi no mono as elements in their pseudo-historical writings.

It’s probably not as neat and simple as “Shinobi no mono gave us ‘ninja vs. samurai’” - we can see with Gluck and with Shirato Sanpei that the idea of ‘ninja’ as fighting for peasants or as social outcasts wasn’t totally unknown before Shinobi no mono - but my best guess is that Shinobi no mono tipped the balance, so to speak, by popularizing the idea of ‘ninja’ as clans of peasants defending themselves against the bullying of the higher-class samurai. The failure of the Anpo riots to achieve their objective would have made Japanese readers very receptive to that idea, and things just kind of snowballed from there; the ‘ninja-samurai’ idea was picked up and repeated over and over by the usual suspects, to the point where it acquired the status of something everyone ‘just knows.’

If this is what did happen it would be a bit ironic, because reading Shinobi no mono (novel or film) as being about ‘ninja vs. samurai’ is a simplistic and reductive reading of what Murayama was trying to get across. One of the points Murayama makes over and over, in fact, is that lower-ranking ninja like Ishikawa Goemon get screwed over by everybody, including their own ‘ninja’ superiors - it’s definitely not as simple as ‘ninja vs. samurai.’

Anyway, I think we’re done with the ‘ninja-samurai’ thing for now. Moving on, I’d like to do something I promised to do at the end of last year and give a rundown of Japanese scholar Yoshimaru Katsuya’s dissection of the historical case for the only supposed historical kunoichi to have a name, the famed spymaster and miko Mochizuki Chiyome.

Donn F. Draeger, “Invisible Men with Secret Weapons” This is Japan (1962 ed; published September 1961), p. 209.

Jay Gluck, Zen Combat and the Secret Power Called Ki (Weatherhill, 1962), p. 110.

Burakumin 部落民.

Hatsumi, Ninja, Ninpō gahō (Akiyama Shoten, 1964; my copy, 1977), p. 30. Japanese text: それは、忍者はいやしいもの、忍法は、ひきょう者の技術と思われたからで、忍者は人間あつかいをされなかった。

Hatsumi, Ninjutsu: History and Tradition (Unique Publications, 1981), p. 7.

Okuse Heishichirō, Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei (Shinjinbutsu ōraisha, 1964; my ed., 1995) pp. 30-31). Japanese text: (3)事を行うに恥を忍ぶべきこと (‘endure shame’), of which Okuse remarks (3)の戒律は、忍者に武士道的良心を去れと教えている点で、甚だ面白い。

Isn't Kamui in the manga of the same name by Shirato Sanpei burakumin?

I believe Ninjitsu would have been "highly illegal" because only samurai were allowed to own swords, and I would imagine in a highly class-restrictive society like Tokugawa Japan, it was probably illegal for non-samurai to learn or practice any special martial arts. (and also most of what they were hired for was for illegal activities of course - assassins, spying, burglary, etc. - unless of course it's on the victor's side ;) )

Always a welcome diversion from my increasingly political timeline…

…unless there’s any historical support for ninja vs neo-fascist?