One Ninja Film to Rule Them All: Shinobi no mono (1962)

How a single film inspired half a century of bad history

The last few posts, we’ve been considering where the idea of ‘ninja’ and samurai as mortal enemies - what I’ve termed the ‘class warfare’ hypothesis - might have come from. We started by looking at Shirato Sanpei’s popular manga series Ninja: The Arts of War, but although the broad outline of peasants fighting samurai is there in the manga, the details aren’t quite right, because ‘ninja’ are more an independent faction than farmers themselves. I think we’re on the right track in looking at 1960s Japanese pop media for the origin of the trope, though, so for today’s post we’ll consider another massive popular depiction of ‘ninja,’ the 1962 film Shinobi no mono by Yamamoto Satsuo.1

Made on a relatively limited budget by a new-ish director, Shinobi no mono proved to be an unexpected hit with Japanese audiences. It gave birth to an entire franchise, in fact, with seven further Shinobi no mono films over the next few years, and the sequence of films would probably have kept on going if not for the untimely death of its leading man, former kabuki actor Ichikawa Raizō the Eighth, from cancer at the age of thirty-seven.2

Film Realism and the Ninja

The Shinobi no mono franchise, and the first film in particular, were immensely influential in shaping the contours of the modern ‘ninja’ myth. In fact, I’d argue that it’s only with the coming of the Shinobi no mono films that we finally see the modern ‘ninja’ in his completed form. By this I mean that basically every aspect of the pop-culture ‘ninja’ as most of us understand him - black hoods, shuriken, assassinations, ‘ninja’ clans of peasants with ‘ninja’ masters, kunoichi, opposition to samurai - is present in these films, and so post-Shinobi no mono we can clearly say that the modern ‘ninja’ is out there as a cultural and media icon.

What makes the Shinobi no mono films even more interesting is that a lot of Western ‘ninja’ writers and enthusiasts have read them as essentially historical documentaries, assuming that the details we see in these fictional films represent things that the historical shinobi actually did. The Amazon blurb for Animeigo’s 2007 DVD of Shinobi no mono, for instance, praises the first film for being “realistic,” while other English-language critics tend to echo this, assessing the film as containing “more realistic depictions of the ninja arts” than previous films that emphasized magical powers.

“Realism” is a tricky word, especially in a film context. The Shinobi no mono movies are undeniably “realistic” in one very specific sense, in that they don’t depict anything supernatural. Shinobi no mono’s ‘ninja’ don’t have the ability to, for instance, magically turn themselves into women, like they do in the works of Yamada Fūtarō. The tricky bit is, though, that “realistic” can mean different things to different people, and I think that in practice a lot of viewers understand “realistic” to mean that Shinobi no mono depicts the historical shinobi as they really were in the Warring States period.

Needless to say, this is a highly debatable claim, and even if it were true, it should be obvious that it’s unwise to base your understanding of Japanese history on historical fiction - which is what the Shinobi no mono franchise is, despite the claims for its “realism.” In fact the situation is even worse than it initially appears, since I can show that multiple early English-language ‘ninja’ writers straight-up used Shinobi no mono as an historical source - that is, they took things they had seen on the screen in Shinobi no mono and presented them to their readers as if the events in the film were documented historical fact.

This might sound incredible on first hearing. Writers like Donn Draeger and Andrew Adams are some of the most respected ‘ninja’ authors of the last sixty years, and certainly among the most widely read. It strains credibility to think that these guys could have been so sloppy and irresponsible as to use a 1962 ‘ninja’ film as a basis for making claims about ‘ninja’ history. Surely nobody would be so stupid as to do that?

If that’s your reaction, you clearly haven’t been here very long.

The Ninja Gets Political: Murayama Tomoyoshi

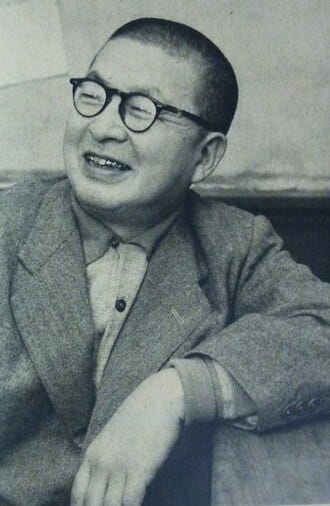

Let’s look now at the background to the film Shinobi no mono itself and how it came into being. The 1962 film itself is based on a novel first published in serialized from 1960 onward by the prominent playwright and left-wing activist Murayama Tomoyoshi.

Like Shirato Sanpei, Murayama was heavily involved in left-wing politics, and being about 20 years older than Shirato Sanpei, Murayama had been active during the 1930s and 40s, when anything with even a sniff of Socialism or Communism could get you in potentially lethal trouble with the Japanese Secret Police. Murayama was in fact arrested on several occasions between about 1930 and 1942 for various political crimes, including joining the Communist Party and speaking out against Japanese militarism.

After Japan’s defeat in August of 1945, Murayama more or less returned to his previous activities in Japanese experimental theater, no doubt very happy to take advantage of the postwar constitution’s guarantees on freedom of speech and conscience. His politics, so far as I can tell, didn’t really change, and it’s no surprise to find that the venue where Murayama began his serialization of his novel Shinobi no mono was The Red Banner (Akahata), the official newspaper of the Japan Communist Party.

By now, I imagine, you’re getting the point: A lot of the people responsible for the most prominent ‘ninja’ works of the early 1960s had politics that were left of center, and this inevitably shaped their presentation of what they thought ‘ninja’ were, as well as his role in Japanese history and culture. As far as I can see, though, none of the early English-language ‘ninja’ writers appear to have realized this fact, or if they did, they appear to have ignored its implications.

Anyway, a year or two after its serialization Murayama’s novel was adapted into a film by the director Yamamoto Satsuo, who was at the time a new arrival at Daiei Films, one of the biggest film studios in Japan. Yamamoto would go on to have a fairly distinguished career as a filmmaker until his death in 1983, but Shinobi no mono was his first film for Daiei, and he had to tread carefully. Yamamoto, you see, also had Communist leanings - in fact, in his autobiography he records that senior figures at the studio had not wanted to hire him for that very reason - and so, when he pitched a film version of Shinobi no mono to the studio head as his first project, Yamamoto strategically neglected to mention that the novel had been serialized in The Red Banner.3 Fortunately the studio head, Nagata Masaichi, had Yamamoto’s back, and so the film did indeed get made, proving to be an unexpected hit.4 Yamamoto then directed the sequel, Shinobi no mono 2 (Zoku Shinobi no mono), the following year, before other directors were given a crack at the franchise for the remaining films.

Ishikawa Goemon: Thief, Legend, Ninja

The action in Shinobi no mono centers on the warlord Oda Nobunaga’s campaign of conquest in central Japan between about 1573 and 1580. As the film begins, Nobunaga is fighting his rivals, the Azai and Asakura clans, in the area north-east of Kyoto:

The men of Iga Province, a way to the south, realize that if Nobunaga defeats the Azai and Asakura there’s a high chance Iga will be next on the list. Nobunaga must therefore be dealt with before he can become too powerful, and the men of Iga vow that they will find a way to remove him from the picture. Iga Province is, as every ‘ninja’ enthusiast knows, the supposed heartland of the historical shinobi, so it’s no surprise to find that the warriors of Iga Province who take on the task are unambiguously identified using the specific word ‘ninja’ throughout the whole film:

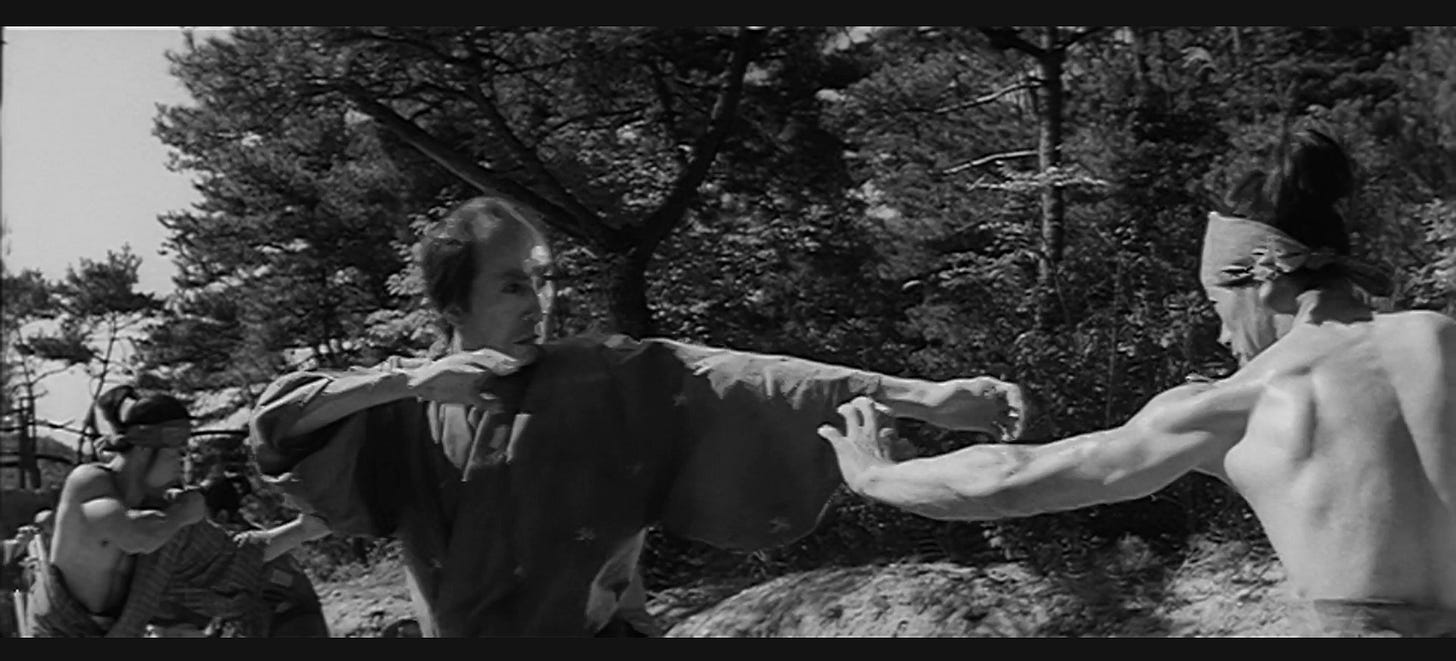

The younger man on the right is our protagonist Ishikawa Goemon, played by Ichikawa Raizō VIII. Goemon, for what it’s worth, probably was a real person, a robber active in the Kyoto region during the 1590s.5 His main claim to fame is that he was executed in spectacularly gruesome fashion by being boiled alive in a large cauldron. After this nasty end, Goemon went on to become a frequently-used character in any number of Edo-period theatrical plays and prose works, morphing over time into a righteous thief figure not dissimilar to Robin Hood. Here, though, he’s re-imagined not so much as a thief but as a warrior who has undergone lifelong training in the arts of stealth, assassination, and covert warfare - which is to say, a ‘ninja.’

Unlike the manga Ninja: The Arts of War, ‘ninja’ in Shinobi no mono are indeed a cohesive social group - a ‘ninja clan,’ if you will. They are at one and the same time lethal assassins and farmers, a point made several times throughout the film. We see one of Goemon’s fellow ‘ninja,’ named Yohachi, at work in the fields as the film opens:

This appears to be Goemon’s life, too - growing crops on the one hand and training in those sweet ninja skills on the other:

Right off the bat, Shinobi no mono is much better fit for the ‘class warfare’ hypothesis, because the ‘ninja’ are basically all peasants, training in the art of ninjutsu both to defend themselves and so that they can hire out their services to warlords. To further strengthen our case, we’d want the film to show the ‘ninja’ way of war to be clearly contrasted with that of the samurai in ethical or social terms. This we get, as the ‘ninja master’ Momochi Sandayū explains:6

Within the first 15 minutes or so of the film, then, the viewer has seen many of the key elements in the ‘class warfare’ hypothesis - ‘ninja’ as primarily peasants, who train in forms of unconventional warfare that are clearly distinguished from the noble and ethical samurai. We maybe haven’t seen the idea yet that samurai despised ‘ninja’ and brutally tortured them if they were captured, but that too will not be long in coming.

I’ll stop here for today, because I’m running out of space. For next time I’ll finish up recapping Shinobi no mono, and then go on to show that early writers Andrew Adams and Donn Draeger were not only demonstrably aware of the film franchise, but also that several of their historical claims about ‘ninja’ exactly replicate moments in Shinobi no mono itself. These observations will, I think, support the case that a large part of the methodology of the 20th century’s most prominent ‘ninja’ experts was to watch 1960s ‘ninja’ movies and then tell everyone that the stuff on the screen had, like, totally happened, for real, dude.

Yamamoto Satsuo 山本薩夫 (1910-1983).

Ichikawa Raizō the Eighth 市川雷蔵八代目 (1931-1969). So-called because quite a few famous kabuki actors passed on their stage names to successors over the generations. The first Ichikawa Raizō had been active two hundred years earlier during the mid-18th century.

Per recollections in Yamamoto Satsuo, Watakushi no eiga jinsei 私の映画人生 [My Life in Film] (Shin Nippon Shuppansha, 1984), pp. 212-14.

Nagata Masaichi 永田雅一 (1906-1985).

Ishikawa Goemon 石川五右衛門 (?-?1594).

Momochi Sandayū 百地三太夫. No dates, because he probably didn’t exist - as even the Iga Ninja Museum admits, noting that there is no historical evidence for anyone of that nomenclature having existed.