The Japanese journalist and critic Itō Gingetsu is, as we’ve just been discussing, probably the originator of the modern concept of the ‘ninja’ as we know it today. I’ve used the last few posts to suggest that Gingetsu’s approach to writing the history of the ‘ninja’ had some rather odd aspects to it, notably that he was using works of fiction to support his case rather than the kind of documentary historical evidence that modern historians might work with. The examples of ninjutsu that Gingetsu uses, for instance, are from the 1777 play The Precious Incense and Autumn Flowers of Sendai, the hugely popular fictional series The Eight Dog Chronicles (1817-1842), and the almost-as-popular Chronicle of the Regent Hideyoshi (Taikōki, first pub. 1626 but widely adapted and read thereafter).

In today’s post, then, I’d like to explain some of the things that I think might have been in the background to Gingetsu’s odd methodology, and which perhaps make it easier to understand why Gingetsu made the choices he did. For some readers this discussion may be a bit abstract, so if you’re not too interested in the intellectual climate that spurred Gingetsu’s thinking feel free to take a pass, and on Saturday we’ll move on to a new topic.

The History Boys

In the 20 or so years before Gingetsu wrote his 1909 Shadow Magic and Illusion Magic, there’d been a significant set of changes in the way that history was written and thought about in Japan. The main figures driving these changes were a small group of historians at Tokyo University, who had been trained in new, modern, and primarily German-inspired approaches to writing history. These approaches, among other things, insisted on a rigorous critical assessment of textual evidence, and the need to attempt to find corroboration from a variety of sources.1 This meant, in many cases, basically discarding or seriously limiting the use of a lot of popular works such as the 14th century war chronicle Taiheiki (‘Chronicle of Great Peace’) on the grounds of unreliability.

Most serious historians nowadays would concede that the Taiheiki and other similar war chronicles aren’t 100% reliable, but in the late 19th century the suggestion that some of the heroes of these works might not have done or said everything the text says was considered unsettling at best. As one example, take the warrior Kojima Takanori (dates unknown), a staunch supporter of the Emperor Go-Daigo against the Hōjō and Ashikaga clans between about 1331 and 1337. Kojima Takanori’s loyalty and bravery in support of the Emperor became legendary; one of the things he did, for instance, was single-handedly track a detachment of Hōjō troops as they carried the Emperor Go-Daigo off to his place of exile, having captured him in 1331. As he was tailing the Emperor, one night Takanori slipped into the Hōjō camp and carved a poem in literary Chinese on a tree to let Go-Daigo know that help was coming:

This is so ninja-ish, I’m actually a little surprised nobody’s ever tried to claim him as one.

Anyway, Kojima Takanori was quite a guy, and was especially useful for the Meiji government, which was trying very hard throughout the late 19th and early 20th century to indoctrinate its citizens in the idea that they too should be loyal subjects of the Emperor. So it’s not hard to imagine how it went down when one particular academic historian, Shigeno Yasutsugu, suggested that Takanori never actually existed.2 Shigeno’s argument was essentially that the Taiheiki was the only known text that mentions Takanori, and since his existence could not be corroborated by other sources, the odds were that Takanori was a literary embellishment rather than a real person.

Shigeno was probably overplaying his hand, for what it’s worth, since subsequent research would uncover a range of circumstantial evidence suggesting that the Kojima were in fact a real warrior clan in exactly the area Takanori is supposed to have been active, and most historians now accept that he likely existed. Still, the gauntlet had been thrown down; Shigeno Yasutsugu and his colleagues were going to significantly raise the standard of proof they were going to accept for historical claims. This would, in time, land Shigeno himself with the nickname “Professor Obliterator” (massatsu hakase), which sounds like a Marvel supervillain but was intended to capture his apparent determination to erase various beloved figures from what everyone had thought was the historical record.3

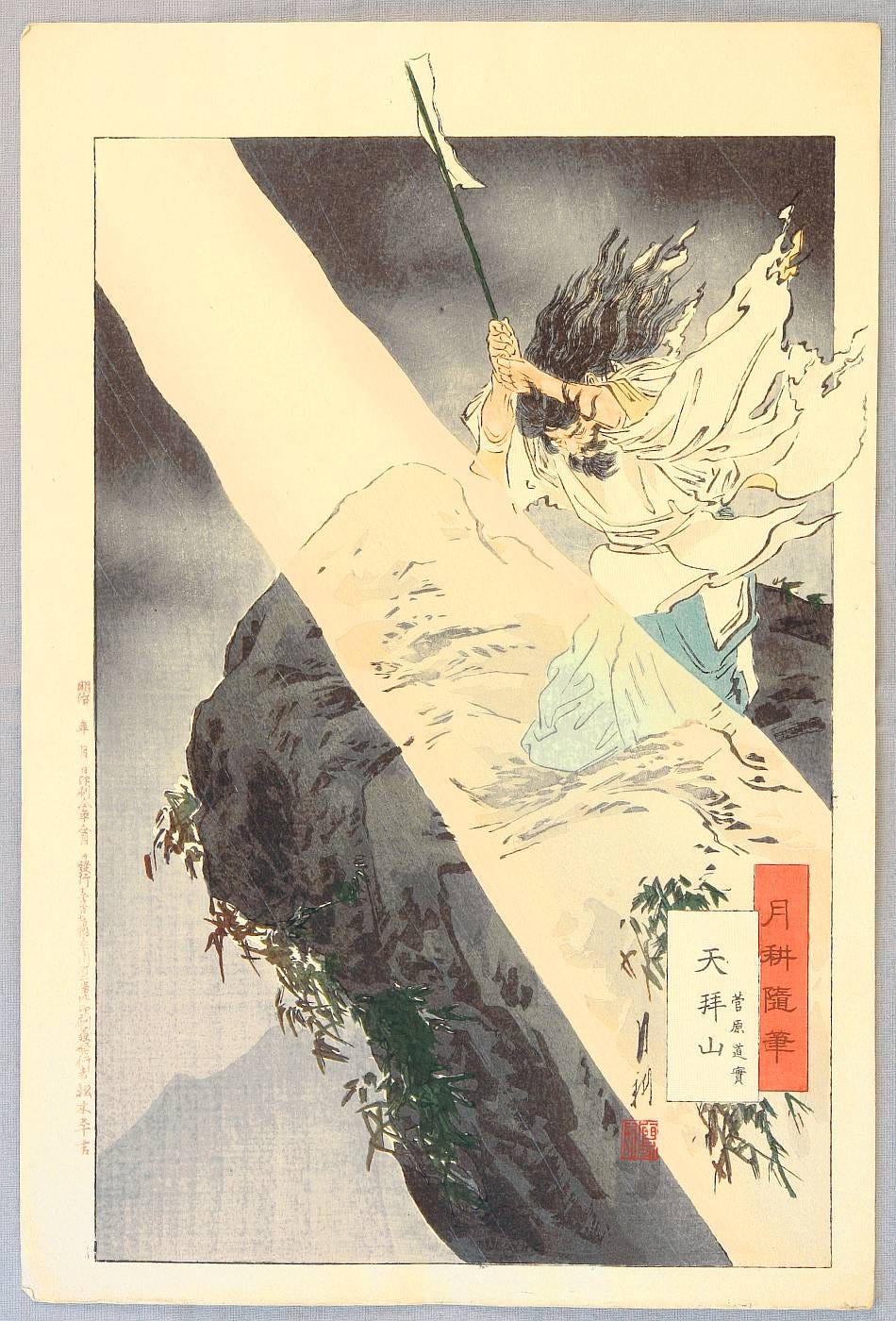

In 1892, Shigeno’s colleague Kume Kunitake took a swing at another famous Japanese hero, the Heian-era legend Sugawara no Michizane.4 Michizane, in life, was a prominent noble, poet, and politician of the late 9th and early 10th century. Caught up in court intrigue, his enemies managed to have him exiled to Kyushu, where he passed away. Legend has it, though, that after his death his spirit returned to kill almost everyone who had screwed him over, most notably by zapping them with a big-ass bolt of lightning:

The only way to stop the smiting, so the story goes, was to lay Michizane’s furious spirit to rest by honoring him, and this was done by making him into the god of learning and scholarship, Tenjin. Anyway, in a pair of journal articles in early 1892, Kume Kunitake laid out his views on all of the stories about Michizane’s ghost and supposed lightning-based vengeance: they were all bullshit. “Total nonsense,” as he put it, “the sort of stuff you should never bring up in front of any reasonably sane individual.”5

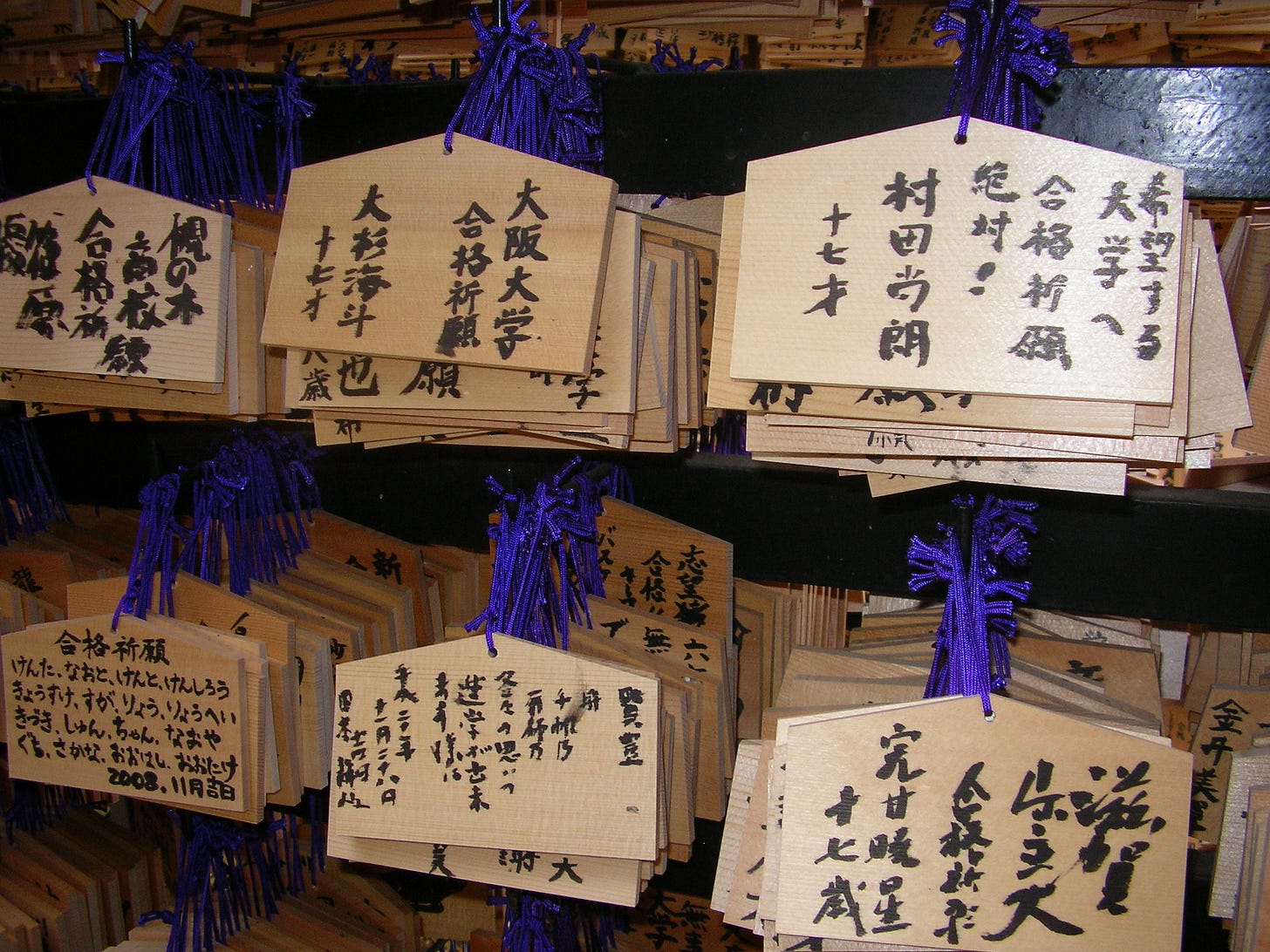

This too pissed off quite a few people, since Michizane’s story was a widely-known one, and he was also regarded as something of a hero. Shrines to Michizane’s deified form of Tenjin are found all over Japan to the present day, in fact, and are very popular among those dealing with the Japanese educational system. People often offer prayers to Tenjin for success in examinations, as I found in Kyoto a few years back:

There are other examples I could give - Kume, in particular, got himself into some real hot water by attempting a critical analysis of Shinto - but hopefully the main point is clear.6 Academic history in Japan had, by the early 20th century, attempted a fairly radical and controversial overhaul of its rules of evidence, moving to exclude - if you’ll allow the legal metaphor - a whole bunch of stuff, like the Taiheiki, that almost everyone had read, enjoyed, and accepted as basically historical in nature. The late Edo-period poet and historian Rai San’yō, whose famous An Unofficial History of Japan (Nihon gaishi, finished 1827) I’m translating, based several whole chapters of his magnum opus on the Taiheiki, for instance.

What does this have to do with Gingetsu or ‘ninja’? Simply put, my strong sense is that Gingetsu really didn’t care for this attempt to upgrade historical methodology. He would, after all, have grown up on semi-historical works like Chronicle of the Regent Hideyoshi or total fiction like The Eight Dogs Chronicles, and I think he wasn’t ready to simply relegate them to the drawer marked “no historical value.” I suspect, in fact, that he was very uncomfortable with the bright line between history and fiction that Kume, Shigeno and their colleagues had attempted to draw, and sought a way to blur that line, or even find a way to use such works to make claims about things that had happened in the real world.

Superstition Ain’t the Way

The way Gingetsu found to get around the problem I’ve just described, of how to bring works like The Precious Incense back from the dustbin of serious history, would - somewhat paradoxically - be the presence of magical powers in the works in question, which is precisely what we’ve just been discussing with relation to ‘ninja.’

It’s worth noting, given how weird some ‘ninja’ writers can get, that Gingetsu never attempts to argue that the magical powers in Edo fiction are literally real. You might have been able to argue that mystical powers were real in premodern Japan, before the Meiji Restoration of 1867, but you couldn’t by the time when Gingetsu was writing in 1909, at least not if you wanted anyone to take you seriously. To be clear here, when I use the terms “premodern” and “modern” I’m not just talking about a range of dates; in Japan Studies, when we use these two terms, we’re talking about two pretty fundamentally different ways of understanding the world and everything in it. The modern way of thinking about the world, for instance, is supposed to be scientific and rational; modern thinking, with a few notable exceptions, doesn’t accept the existence of genuine supernatural powers like the ability to fly, change shape, or turn invisible.

Instead, modernity tends to insist that what might appear to be done by magic always has some kind of logical explanation. So to return to a couple of examples we used a few posts ago, because Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes story The Hound of the Baskervilles is a modern realistic novel, the phantom hound can’t literally be a glowing phantom. There has to be some kind of real-world explanation, and that duly appears when we find out that the spectral apparition is in fact a real dog covered in phosphorescent paint. In a premodern work such as Macbeth or The Precious Incense and Autumn Flowers of Sendai, by contrast, there isn’t necessarily anything problematic about a character having literal magical powers; the author is under no pressure to provide us with a real-world explanation, because a decent chunk of the audience probably does accept that such powers could exist.

These are obviously not completely iron-clad rules (consider the popularity of Harry Potter, for instance), but they illustrate the point that there were some very big differences between modern and premodern Japan in terms of how each thought about the world. The historian Gerald Figal, who teaches at Vanderbilt, has a fascinating book on the cultural ructions this transition caused during the Meiji period, which I want to briefly quote from here. The passage I’m interested in comes from a famous 19th century oral storyteller and performer by the name of San’yūtei Enchō (1839-1900) who was well-known for his ghost stories up to the end of the Edo period (1600-1867) and for a few years after.

Figal quotes Enchō as expressing frustration later on in his career that, with the coming of “civilized” modernity, he now needed in effect to add a disclaimer to his stories, to the effect that what he presented as ghosts in his stories were really the effects of psychological imbalances:

What are called “ghost stories” [kaidan-banashi] have greatly declined in recent times; there is hardly anyone who does them at the variety halls [yose]. That is to say, since there are no such things as ghosts and they all have come to be called neurosis [shinkeibyō], ghost stories are unseemly things to the professors of civilization [kaika senseikata] ...By saying that it's a neurosis because there's no such thing as fox-possession and goblin [tengu]-abduction, they completely fob off any and all frightening things on neurosis.7

The point Enchō is making here is that in the good old premodern days, you could simply tell a ghost story and not have to worry about what it really was. Now that we’re all modern, however, you have to maintain that ghosts aren’t real and that what appear to be ghosts are all in the beholder’s head, the result of what was at the time called “neurosis.”

This notion, that apparent magic might actually be a mental effect produced by the mind of the beholder, is one that I think Gingetsu found very interesting. It explains why he devoted an entire chapter of his 1909 book to the topic of hypnotism, for instance, since on the surface hypnotism - at least, as it was described in Japan at that point in time - seemed to offer the potential to alter the recipient’s consciousness and allow for the perception of seemingly mystical things. This echoed down into other ‘ninja’ writers too, by the way; it probably explains why Oda Hidehisa tried to use “group hypnotism” to explain the story of Katō Danzō swallowing a bull, and Stephen K. Hayes has a whole chapter about how ‘ninja’ used hypnotism in his 1985 The Mystic Arts of the Ninja: Hypnotism, Invisibility, and Weaponry. I think the attraction is that hypnotism, rather like the “grain of truth” argument, is a superficially plausible way of explaining how the apparently magical might actually be real. That said, Gingetsu actually denied the connection, writing that “Ninjutsu is not a type of hypnotism, or anything like it; ninjutsu is simply ninjutsu.”8

So this is what I think was going on with Gingetsu - basically a form of nostalgia. I think he wasn’t ready to let go of the idea that the stories he’d enjoyed so much in his childhood weren’t in some sense real, and he found a way to make that argument by creative application of the modern epistemic logic that magical powers have to have some kind of rational explanation. I suspect that Gingetsu himself would probably be shocked if he could see what his work would later bloom into, but there we are.

Anyway, I think it’s time for a new topic. Since I promised to do so a while back, how about we take an in-depth look at one particular 60s ‘ninja’ move, the extremely off-beat 1964 kunoichi movie Kunoichi Ninja Magic?

If you’re interested in a more detailed discussion of the new historical approach and some of the controversies surrounding it, there’s some pretty good coverage in two English-language books: Margaret Mehl, History and the State in Nineteenth-Century Japan (New York: St Martin’s Press, 1998), and Michael Brownlee, Japanese Historians and the National Myths (Vancouver: University of British Columbia Press, 1997).

Shigeno Yasutsugu 重野安繹 (1827-1910).

Massatsu hakase 抹殺博士. This was not supposed to be a compliment.

Kume Kunitake 久米邦武 (1839-1931); Sugawara no Michizane 菅原道真 (845-903).

Kume Kunitake, “Tenmangū wa ikanaru kami zo,” [What Manner of Deity is Tenjin?] Shigakkai zasshi [Journal of the Historical Society] No. 27 (February 1892), p. 24. Japanese: 精神の全き人の前には陳べ難きうわ言. Wouldn’t you know it, I wrote a whole article about Michizane’s Meiji-period reception a while back (unfortunately paywalled).

Basically Kume argued that Shinto was a primitive and outdated religion that had no place in modern Japan, and you can imagine how that was received. For a full discussion, see “Scholarship and Ideology in Conflict: The Kume Affair, 1892,” Monumenta Nipponica 43.3 (Fall 1993): 337–57.

San’yūtei Enchō, Shinkei Kasane ga fuchi, in Enchō zenshū, ed. Suzuki Kōzō; Sekai bunko, 1963-64), 1:1-2; quoted in Figal, Civilization and Monsters: Spirits of Modernity in Meiji Japan, Duke University Press, 2000, p. 28.

Gingetsu, Ninjutsu to yōjutsu (1909), p. 67. Japanese: 催眠術の一種でもなく、催眠術のやうなものでもなく、忍術は唯だ忍術で […]

I admit that actually the history of ninja is just a history of pop culture, but what about traditions like ryuha or schools, such as iga, koka, togakushi, are they all made up history?

Another excellent contribution with high educational value and relevance that goes far beyond the boundaries of "ninja studies." The clash between the modern and premodern is rarely emphasized in our context when interpreting Japanese history. The attempt to understand supernatural phenomena in a "modern" way—that is, through rationality and modern science—is also mentioned in Yamada's History of the Ninja in connection with the boom of interest in hypnosis during the Meiji period. In this context, one also encounters the term ninjutsu. In the 1910 book Hypnosis at your will (催眠術自在), there is a chapter on wizardry (senjutsu 仙術) and "shadow magic" (ninjutsu 忍術), where ninjutsu, of course, has nothing to do with martial arts. Even as late as 1917, the Tokyo Society for the Study of Hypnosis published Secret tradition of Ninjutsu and Kiaijutsu (忍術気合術秘伝). It would likely be interesting to observe how rapid and widespread Gingetsu Itō’s influence was in shaping the image of ninjutsu.