What's Up With The Illustrations in Zoughari's "Ancient Shadow Warriors"?

In which we find an author who appears not to look at his own material

In the previous post I documented what appears to be substantial plagiarism in Dr. Kacem Zoughari’s 2010 book The Ninja: Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan: The Secret History of Ninjutsu, published by Tuttle. The apparent plagiarism is only the most serious of many problems with Ancient Shadow Warriors, unfortunately, so in this and the next post I’ll explain some of these other problems that combine to make the book so catastrophically bad (“Other than that, Mrs. Lincoln, how was the play?”).

Today we’re going to take a brief look at the use and abuse of pictorial evidence in Ancient Shadow Warriors. I’ve written about this topic previously, making the point that ‘ninja’ writers are appallingly careless in their use of Japanese prints and other pictorial evidence. It’s clear on closer examination that many ‘ninja’ authors have only the haziest idea as to what the prints they include in their books actually depict and are using the prints essentially for decoration. Unfortunately, Dr. Zoughari’s book exemplifies this tendency in spades, as it contains numerous illustrations or prints that its author appears to know little or nothing about, despite his authoritative-seeming captions.

The Answer is Noh

Let’s start with an easy one. On p. 28 of Ancient Shadow Warriors, we’re presented with a reproduction of this document:

As you can see, the caption says that this is Kōyō gunkan (‘The Military Annals of Kai Province’).1 Kōyō gunkan is an account of the life and times of the legendary warlord Takeda Shingen of Kai. It’s a popular text among ‘ninja’ enthusiasts, since it contains a lot of information about Shingen’s practices of clandestine warfare.

Not that that matters, because the document is not Kōyō gunkan.

It is in fact a guide to effective acting in Noh drama by the famous playwright Zeami, entitled Fūshi kaden (‘Transmission of the Flower of Acting Style’).2 Finished in 1418, Fūshi kaden predates Kōyō gunkan by almost two hundred years and has no connection whatsoever to “the Takeda family’s tactics and strategies.” So it’s a foundational text in Noh drama, but it has nothing at all to do with any of the topics discussed in Zoughari’s book. Maybe he just thought it looked pretty.3

Simply looking at the Japanese title on the right-hand side would be enough for anyone who can read Japanese to tell what the document is - the graphs are 花伝第六花修云, which means: “A Quote from Volume 6 of Fūshi kaden,” and the remainder of the text matches the text of Fūshi kaden, as you can confirm here if you have the language ability.

I honestly don’t get how this error came about; it beats me why Fūshi kaden would be in the mix in the first place, given its utter irrelevance to Zoughari’s topic. All Zoughari had to do to avoid the mistake - and we’ll be saying this a few times - was to look at his own illustration.

The Greatest Village Temple the World Has Ever Seen

A page or two on, we have this photo:

This is certainly a very impressive structure for a lowly village temple! Or it would be, if it actually was a village temple. It’s not - it’s the famous Tōdai-ji Temple in the nearby city of Nara, about 15 miles west of Yagyū Town in Nara Prefecture. You can confirm this for yourself by checking Zoughari’s image above against depictions of Tōdai-ji on Google Images.

The Tōdai-ji is one of the most renowned Buddhist temples in Japan, founded in 738 AD and designated as a UNESCO World Heritage site, so this mistake is just plain bizarre. It’s a bit like putting up a picture of Notre Dame and claiming in the caption that it’s a church in rural Georgia. Again, I honestly can’t understand how this could have happened; I assume Zoughari went to Yagyū himself, so I wonder how he could have failed to notice that the picture he put up wasn’t of the village temple.

The City of Tokyo, Population 2,500

A similar, even more bizarre example:

I…what? “The entrance to Yagyū Castle?” This is the entrance to the Imperial Palace in Tokyo, as almost anyone who’s spent time in Japan’s capital would know. It’s a view of the famous ‘Double Bridge’ (Nijūbashi) that leads into the palace precincts; you can see it from several different angles through Google Images, again, or go there virtually through Google Maps and see for yourself. The lamps and the bridge are very distinctive and instantly recognizable.

Tokyo is a bit under 300 miles from Yagyū village, and the Imperial Palace is one of the most famous landmarks in the city. Unless someone in Yagyū took it upon themselves to build an exact replica of Nijūbashi in the village, I honestly have no idea how this mistake could have happened.4

PSA: How to Identify Women

And then there’s this:

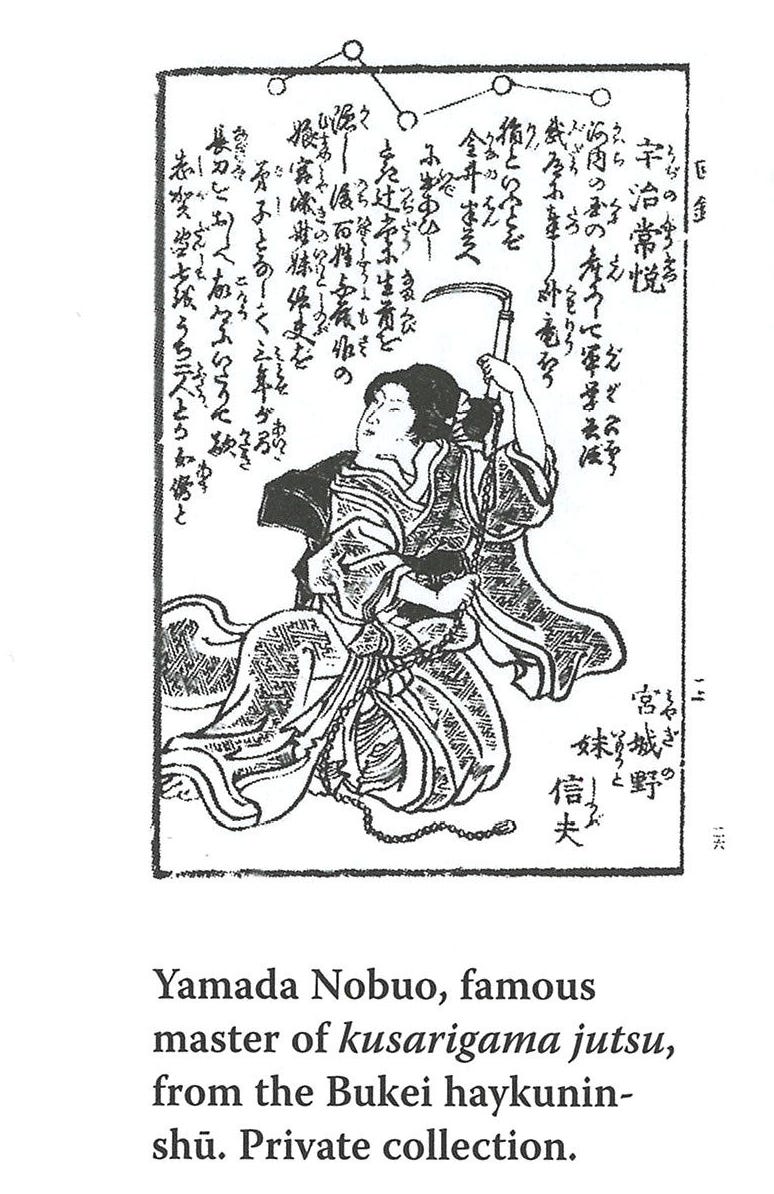

I’m not sure which ‘Yamada Nobuo’ Zoughari is referring to - I can’t find a reference to any historical figure by that name. But the figure very obviously isn’t ‘Yamada Nobuo,’ because Nobuo is a male name, and the figure is clearly a woman, as you can tell at a glance from her kimono and hairstyle. In fact, as the Japanese text in the bottom-right says, this is Shinobu, one of the two sisters Miyagino and Shinobu. They’re well-known as the heroines of an Edo-era story in which the two sisters secretly trained in the martial arts to avenge the murder of their father.

Again, all Zoughari had to do was look at his own print, and he would have realized that the figure in the print is a woman.

A Grave Error

Next:

Uh, no. This isn’t the grave of Hattori Hanzō Masanari (1542-1597). It’s the grave of Hattori Masayoshi (1845-1886), his descendant three hundred years later. I didn’t have to do any specialist research to figure this out, by the way - I just had to look at the picture. Masayoshi’s name is right there in the image on the front of the memorial marker, and his date of death - Meiji 19, or 1886 - is plainly visible on the right hand side.

Again, how did Zoughari get this wrong? Did he, like, shuffle his illustrations and deal them out blindfolded, or something?

The Ninja Art of Stylish Yet Cozy Headwear

Other examples suggest that Zoughari is simply guessing as to what his images depict. Here, for instance, is a perfect example of a warrior wearing a ‘ninja’ hood, or so Zoughari tells the reader:

It took me about thirty seconds of Googling to ID this print. It’s a man called Mutsu Munemitsu, a fairly high-ranking samurai who rose to become Foreign Minister to the Meiji government. So…not a ninja. In any way.

And the hood? That’s a garment known as a Sōjūrō hood (Sōjūrō zukin), a piece of headgear for men that was popularized by a kabuki actor in the 1730s and which, you will not be surprised to hear, has absolutely nothing to do with ‘ninja.’

Not so much the uniform of the feared and lethal assassin as a chic accessory that keeps your ears warm in winter.

A Common Source?

I find the range and nature of the mistakes show above to be truly baffling. I genuinely don’t get how you end up putting illustrations into a book without knowing what those pictures are or without noticing that your captions are obviously wrong.

On reflection, though, I do have a theory as to what may be going on here. One of the things that I’ve noticed in reading through the major English-language ‘ninja’ writers from the 70s onward - Adams, Draeger, Stephen K. Hayes, Turnbull, and now Zoughari - is that they’re all using more or less the same fairly limited set of Japanese prints and photos. I’ll write more about this in a future post, but here’s a quick example: the below print of the fictional sorcerer Nikki Danjō from the mid-Edo kabuki play Meiboku Sendai hagi appears in Adams (1970), in altered form in Draeger (1971), and in its original form in Hayes (1985):

It strikes me as highly unlikely that all of the above ‘ninja’ writers are actually doing original research in art history; that is to say, doing their own searches through archives of Japanese pictorial art. I think they’re all getting these pictures from one main source, and I think that that source is probably ninjutsu master Hatsumi Masaaki himself, the Iga ninja museum, or some other similar party with an interest in promoting ‘ninja’ lore to foreign writers. I suspect that the party in question has a big collection of Edo and Meiji prints and photos, and that they provide these to English-language ‘ninja’ writers with assurances that these materials are pictorial evidence for the historical shinobi. The writers in question take these assurances at face value, stick the prints in their books without bothering to check for themselves, and voilà - that’s how this happens.

I have no direct evidence for the above, but it seems like a reasonable explanation. It would also explain why, as you may have noticed while reading the captions above, almost every image in Zoughari’s book is attributed to “Private Collection.” I suspect that “private collection” is Hatsumi’s, and that this may explain how it was possible for Dr. Zoughari to include a lot of prints in his book without knowing what a lot of them are: He was given them by Hatsumi or some other “private collection” and just stuck them in the book, without taking the time to check them.

I’ve chosen to focus on the illustrations not because they seriously affect the book’s argument, but more because of what they say about the general level of care and attention that went into Ancient Shadow Warriors. The book falls far below the standard you would normally expect from any publisher, let alone one as prominent as Tuttle. It is an appallingly slipshod and careless book, and I think Tuttle’s readers have a right to expect better quality than this in return for their hard-earned cash.

I’m not done yet, by the way. If the mis-attribution of all the images is annoying but not particularly serious, the next issue I want to tackle is far more significant. That issue is the mis-representation of sources in Ancient Shadow Warriors. Simply put, on more than one occasion Dr. Zoughari’s cited sources do not say what he claims they say.

Kōyō (not “Koyō, btw”) gunkan 甲陽軍鑑. Written c. 1615.

Zeami 世阿弥 (?1363-?1443); Fūshi kaden 風姿花伝.

If you’re interested, there’s an English translation of Zeami available from William Scott Wilson.

There are really a lot of cases like that. On p. 37 the description says "The entrance of Mochizuki’s ninja museum in Iga’s Ueno city, Mie prefecture, private collection." Of course it isn't. On the left pillar it says 甲賀流忍術屋敷 (Kōga-ryū ninjutsu yashiki), so it's in Kōka-shi, Shiga pref. (https://www.kouka-ninjya.com/la_en/). And many more (as you've mentioned).

The overall editing is terrible, including the transcription of Japanese terms. I wonder what you make of note 28 on page 183—how on earth does "hata" become "Hastened"?

I have a hypothesis about the whole thing: In the Acknowledgments, Zoughari thanks a certain Mr. Ray A. Letter. Given the "Mr.", I would guess this person is not involved in Bujinkan, Japanese Studies, or anything related. Maybe he was in charge of the final version. Perhaps Zoughari told him something like, "Find an image of the Yagyū villa here," and the collaborator thought, "OK, seems like we need a picture of some typical traditional Japanese building. Any should work..."—and voilà. Just a conspiracy theory, I know.

That said, the entire work is a terrible advertisement for INALCO graduates' academic integrity, meticulousness, etc. The repeated use of "Dr. Zoughari" everywhere is a clear attempt to establish credibility through academic titles—a weak argument, if you ask me. In effect it casts doubts on other people from INALCO as well. I'm looking forward to your take on Pierre Souyri's work (if you're thinking of it).

Thanks for all the great work. I'm a big fan.