Let us continue, then, with our discussion of Nakajima Sadao’s 1964 ninja film Ninja Lady Magic (Kunoichi ninpō). Where we’d left it last time was that in the closing moments of the film, Tokugawa Ieyasu’s daughter Lady Sen has made it to Final Girl status; she’s escaped the blades of the Iga ninja assassins sent to kill her unborn child, and her son is duly born (although not from her body - it’s a long story).

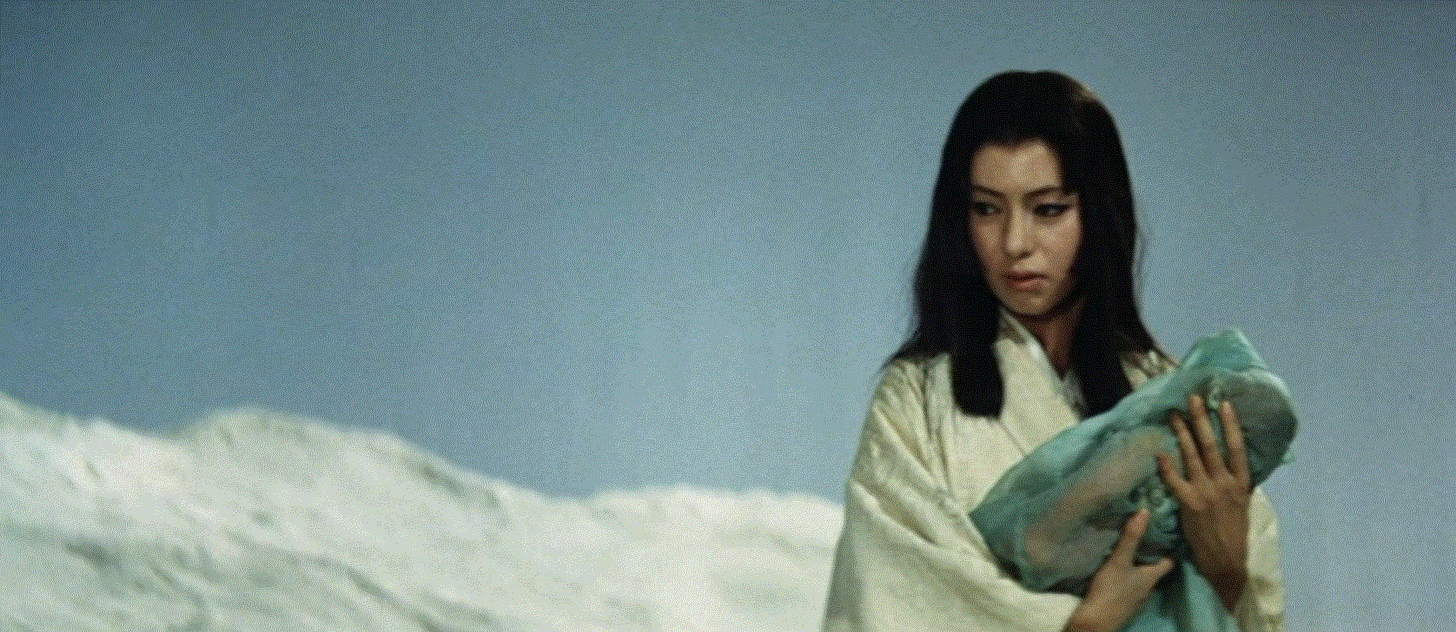

So as we wrap up the film, Lady Sen holds her newborn baby in her arms, as seen in the splash image above, and greets the rising sun:

The sun then dissolves into…actually, I’m not entirely sure. It looks like one of those color-blindness tests. Anyway, this image is overlaid with our two ghost-narrators, Sanada Yukimura and Sarutobi Sasuke, who decide that their work is now done and they can depart for the next life. Or try to, anyway, as Yukimura apparently takes a wrong turn:

The very final twist comes the following year in 1616, as Tokugawa Ieyasu lies dying (as he did in real life). Priests are summoned to attend on him, only to divine that:

Yes indeed - this is Lady Sen’s doing, for we see that her final act of the film is to somehow avenge herself on her father for treating her less as a human being and more as a walking womb. The last shot of the film, which I seem to have forgotten to screenshot, is Lady Sen walking dangerously up to the camera and smiling into it, leaving no doubt who was really responsible for Ieyasu’s death.

What Did I Just Watch?

At this point you’re probably entitled to ask: What the hell, Rob? What are you doing walking us through this lunatic fever dream of a film that no one’s ever heard of anyway?

So I’d say two things in response. The first is that, as ridiculous as many of them are, pulp ninja films are a fairly big part of what the ‘ninja’ phenomenon really is and was. The idea of ninja purely as an historical reality, which is what you mostly get in the English-language literature, captures only a very small part of the whole cultural phenomenon as it developed from the 60s to the 80s and beyond. What’s more, since it’s often the case that the fictional works influence or give rise to the historical claims, we can’t simply wall off the fictional works and pretend that the historical stuff has nothing to do with it.

The second thing is that as I was digging into the story of how Ninja Lady Magic came to be made, I turned up a fair bit of stuff that’s really interesting in terms of Japanese film history. Parts of the story of how the film got made are freaking hilarious, even more so than the film itself, and I think the story is worth sharing. All the more so because pulp films like Ninja Lady Magic almost never get any coverage in conventional academic studies; to the best of my knowledge, no serious academic working in English or Japanese has ever written anything about the film or shared any of the info available about it in Japanese.

And so, ladies and gentlemen, that solemn duty falls to me.

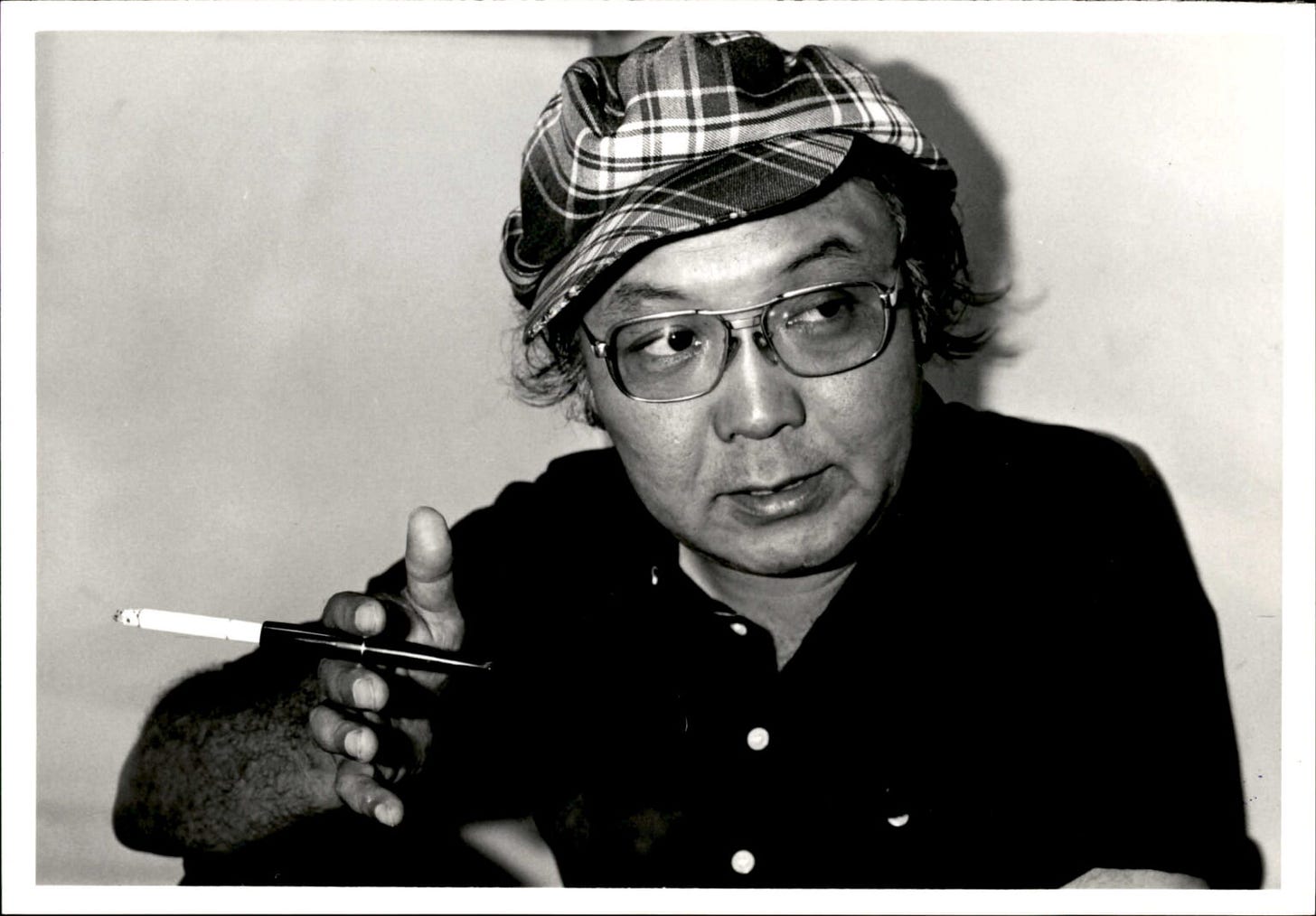

“At First We Tried to Do It As A Comedy”

It’s probably helpful to know that Ninja Lady Magic was in fact director Nakajima Sadao’s directorial debut. He’d joined Tōei Studios in 1959, straight out of college, and probably would have been very happy about landing the position. Tōei was (and is) one of the largest film and media companies in Japan, so on balance Nakajima had done well for himself. The way that Japanese film studios worked in those days was that you were expected to serve a fairly long apprenticeship before being allowed to direct a film for yourself. The legendary Kurosawa Akira, for instance, worked in various minor roles or as assistant director for seven years before being allowed to take full charge of his first film, so when Nakajima was given his solo directorial debut after only five years with Ninja Lady Magic in 1964, he was therefore ahead of the curve and probably pretty happy about getting his shot.

Or perhaps not. You see, although the 1950s and early 60s had been a true golden age of Japanese cinema, giving us such immortal classics as Tokyo Story, Rashōmon, The Seven Samurai, and Ugetsu (the latter one of Martin Scorsese’s favorite films of all time, apparently), things had changed by the mid-1960s. The ‘64 Tokyo Olympics had caused a boom in TV ownership in Japan, with people buying boxes to watch the athletes, and TV was starting to eat the lunch of a lot of the major movie studios. The movie studios were therefore under a fair bit of pressure to find things they could do that TV couldn’t, in a bid to keep people interested.

In a much later interview at a film festival in Kyoto in 2016, Nakajima takes up the story:

So then were told by the producer Okada, the head of the Kyoto studio, to “stop bitching and come up with a plan to fix this [decline in viewers].” What we put forward, pretty much as a joke, was [Yamada Fūtarō’s novel] The Ninja Lady Magic Scrolls, because there was no way they’d ever let that through.

But the thing was, as soon as Okada figured out that Yamada’s original novel had been pretty popular, he said, “Right, we’re doing it. You’re directing. Nobody else’ll be willing to do it.” So that’s how I got saddled with the director’s job.

Normally for a director’s debut work you’d get a low budget and have to work in black and white, but Ninja Lady Magic was color and we got a generous budget to work with. Around that time my classmate from university Kuramoto Sō had just packed it in as a writer for radio and started working on movie scripts, so I got him to write the script.1

I love everything about this. Basically the film was made almost as a dare - half joke and half shock project, to do something a bit racier than was possible on TV.

Anyway, given the benefit of half a century of hindsight, how does Nakajima assess his debut work?

Watching Ninja Lady Magic now, I’d have to say it’s not so much a ninja movie as it is a film exploring psychological hang-ups about mother figures (mazakon eiga). At first we tried to do it as a comedy, but the way we chose to do it, it ended up a bit heavier.

[Takahashi Kenji, the interviewer] There’s the scene where Lady Sen appears holding the baby in her arms and states that “It’s not about Toyotomi versus Tokugawa, it’s about men versus women.” So we end with the idea that ‘motherhood is stronger than anything,’ right?

This exchange helps answer the question of why Ninja Lady Magic is so confusing. Basically, nobody working on the film was entirely sure what they wanted the film to be, seemingly unable to decide among making it an historical drama, a comedy, soft porn, or an exploration of 1960s gender issues.

Takahashi, the interviewer, also calls attention to another confusing aspect of the film, which is the ninja magic and all of its effects. He notes that the film is very abstract in its presentation, which makes it difficult to tell what’s happening at times, particularly if you haven’t read the novel on which it’s based. Nakajima responds:

The thing is that a lot of ‘ninja magic’ is basically impossible to film. We didn’t have much in the way of special effects in those days, you see. The final scene [in the snowy mountains] is filmed on a set, and I don’t think you could actually film it against a realistic background. And then there’s the switching of the baby from one womb to another, which is just pure fantasy (kisō tengai).

Speaking of ninja magic:

[Takahashi] And as we’ve come to expect from ninja, they always call out the name of the magic they’re using. Like “Ninja magic: Evaporating Dew” (tsuyu-garashi).

[Nakajima] Yes, it’s supposed to be “withered stalk” (tsutsu-garashi), but the film censorship people told us to change it, so we went with “evaporating dew.” I actually think that one’s more vulgar (laughs).

[Takahashi] You also have a setup whereby the ghosts of Sanada Yukimura and Sarutobi Sasuke watch what the female ninja are doing. What was the purpose of that?

[Nakajima] They’re there to explain what’s going on. And also, we used a lot of high angle shots, because we wanted to make the film seem like a traditional Japanese narrative picture scroll (monogatari emaki), but it didn’t really come off quite right. There are scenes where it seems like someone is peeping in through a paper screen, but I guess we weren’t able to properly communicate to the artistic staff that we wanted it to look like a picture scroll.2

And so Takahashi wraps up the interview:

[Takahashi] It’s often said that a director pours his very essence into his debut work, isn’t it?

[Nakajima] Yeah, and mine was a film about ninja sex magic, which didn’t exactly do me any favors career-wise. You don’t wanna know how many project proposals I had to submit after that before they’d let me shoot anything set in the contemporary world.

So there you have it. A film that started out as an attempted joke by a rookie director, only for his producer to take him seriously and put him in charge, and for the director then to realize that he didn’t really know which of four or five different genres he wanted his movie to be. This is simply brilliant, I have to say.

Anyway, so with all this stuff going on, surely Ninja Lady Magic must have been a bomb for the ages, right? Total disaster critically and financially?

Well, about that…

The full Japanese text of the interview is readable here (after a Captcha) for anyone to check if they’re inclined, so I won’t include the text in the post itself to save space.

I updated the previous post to reflect this. The sub-titler heard the first word right, but confused two different meanings of tsuyu (‘monsoon’ 梅雨 vs. ‘dew’ 露). For what it’s worth, the word tsuyu in Japanese does in fact have erotic overtones dating back at least to the classical period.

I think this (in the interview) is really interesting: そもそも忍術が、映像化するには無理のあるものばかりなのです。 [Afterall, ‘ninjutsu’ is mostly about things you just can’t make to get on screen.] (my poor alternative translation) This shows, what Nakajima considered - and still does - to be ‘ninjutsu’. If it was ‘just a martial art’ he wouldn’t think so, I guess. Perhaps, Hokusai felt something similar when drawing ‘ninjutsu’ as one of the Bugei 18pan…