In Which I Publish a Peer-Reviewed Article About Ninja

Time for a spot of shameless self-promotion

I am, for my sins, a professional academic, and as such am expected to publish in peer-reviewed venues once in a while. As fun as this Substack is, these posts won’t count for much when the time comes to apply for promotion to full Professor here at ASU. So I figured I’d better get on that, and here’s the result:

“The Fiction of the Ninja: Ishikawa Goemon, Shinobi no mono, and English-language Popular History,” Japanese Language and Literature Vol. 59 No. 1 (April 2025), pp. 43-78.

The journal is Japanese Language and Literature, which I chose for a couple of reasons. One, it’s a good journal, and two, it’s open access, which means that the article itself is freely available to anyone who’s interested rather than locked away behind an academic paywall. This latter point matters, by the way; the abysmal quality of work on the ‘ninja’ in English is a matter of public concern, and I don’t think you can begin to fix that if you’re publishing stuff that general readers can’t access.

That said, I realize that academic writing isn’t necessarily everyone’s cup of tea, and that some of us don’t have the time to plow through a 30-page article. Today, then, I’ll give you the TL:DR version, and you can read the full thing at your leisure if you really want to. I’ll also, in the next couple of posts, add some material that didn’t make it into the final article, concerning the practicalities of the poison-thread technique, then some fun with Roald Dahl - yes, that Roald Dahl - and the 1967 James Bond film You Only Live Twice.

“The Fiction of the Ninja” - TL:DR Version

The article itself is about one of the most famous ‘ninja assassinations’ in the English-language literature, the attempt by the thief Ishikawa Goemon to kill the warlord Oda Nobunaga by dripping poison down a thread into Nobunaga’s mouth as he was sleeping. I wrote about this claim a month or so back, contending that (a) this never happened, and (b) the point of origin for the claim was ‘ninja’ writer Andrew Adams, who in his 1970 book mistook a scene from the 1962 film Shinobi no mono for a real historical event. So if you’ve been following my stuff here lately, the basic point of the article will already be familiar.

The poison-thread thing, for the record, is everywhere in the English-language ‘ninja’ literature; if you check footnote #2 to my article, you’ll see I counted at least fifteen separate publications that mention it, none of which say what the source evidence for the claim actually is. This struck me as odd, because I’d come across the alleged ‘ninja,’ Ishikawa Goemon, in my work on Edo-period literature, but I’d never heard of the poison-thread thing. So, I set out to try to identify what the source for the claim might be.

To start with, someone named Ishikawa Goemon probably did exist. He appears to have been a robber or bandit active in the Kyoto region in the mid-1590s, and is most famous for the manner of his death. Captured by the authorities, he was executed in 1594 by being boiled alive in a large cauldron:

This is probably one of the most famous (and gruesome) deaths in Japanese history, and for centuries thereafter in Japan a metal bath-tub would be known as a ‘Goemon Bath’ or Goemon-buro in its honor.1

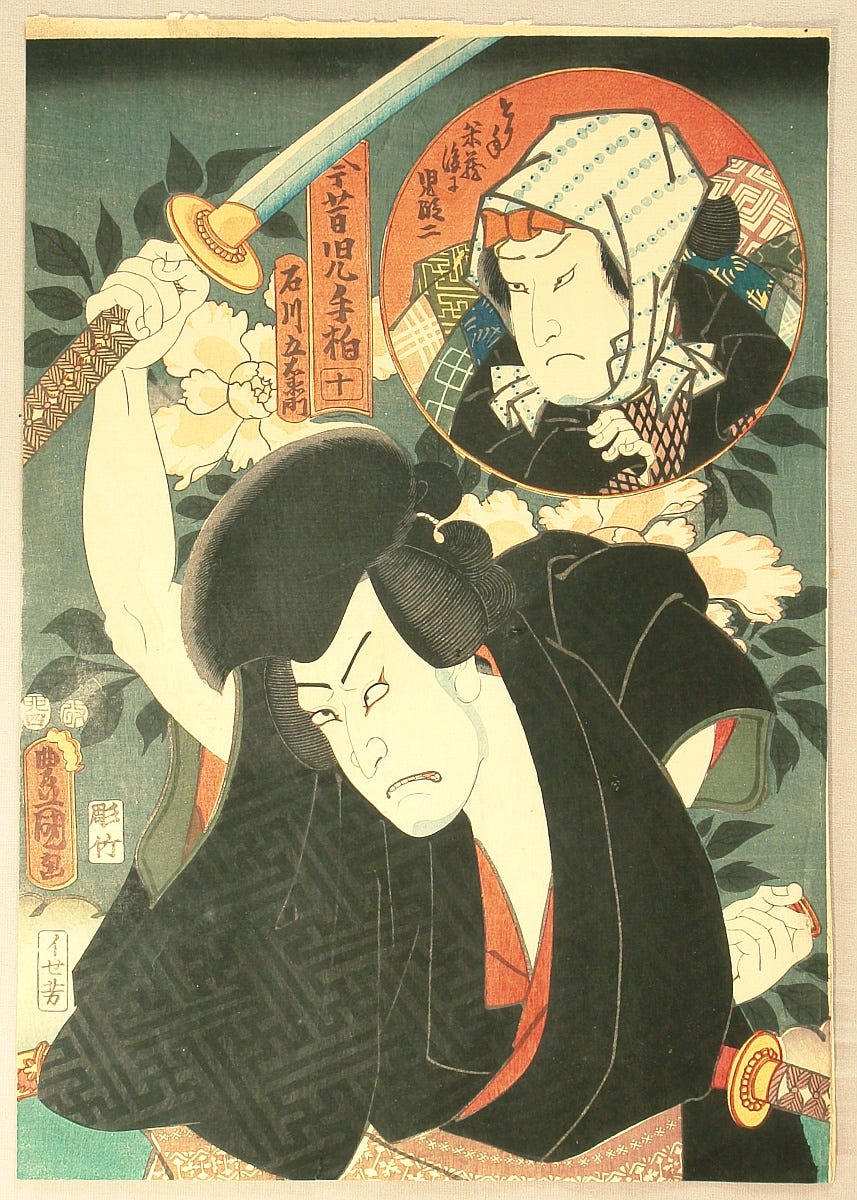

The documentary evidence concerning Goemon is fairly limited; a couple of near-contemporary sources mention a band of thieves being boiled alive in the summer of 1594, and the name Ishikawa Goemon seems to have come to be associated with this event some time afterward.2 So it seems likely that an Ishikawa Goemon existed, that he was a robber, and that he was executed by being boiled alive; but the problem is that almost everything about Goemon’s life beyond that is at least uncertain and in most cases probably fictional. You see, in the centuries that followed Goemon became an incredibly popular character for works of stage drama and prose fiction. He appears in dozens of kabuki and puppet plays and a number of widely-read fictional narratives as well, usually portrayed as a rival and antagonist to the conquering warlord Toyotomi Hideyoshi during the 1590s.

As you might expect, many English-language accounts of Goemon don’t seem to realize that most of the supposed details about his life are wholly or semi-fictional. The English-language Wikipedia page about Goemon, for instance, contains several “facts,” such as the idea that Goemon’s son was executed along with him (as in the Kunisada print shown above), that are in reality plot points from much later stage works.3

The Stalker in the Attic → Shinobi no mono

I spent a fair bit of time, then, trying to see if I could find the Goemon poison-thread story in the Edo-period literature. From the start it struck me as unlikely that this was an Edo-period story, because it has Goemon trying to kill Nobunaga, and Goemon’s enemy in almost every Edo-period story is Hideyoshi, who came after Nobunaga. The setup for the story, in other words, seemed wrong for Edo-period literature; it’s a bit like having Robin Hood fight King Richard I rather than his traditional antagonist the Sheriff of Nottingham.

Not finding the story in the Edo-period literature, I decided to look at the one venue I knew for certain had Ishikawa Goemon using the poison-thread method of assassination, which was the 1962 ‘ninja’ movie Shinobi no mono, and see if we could work backward from there. So I went and read the 1960 novel Shinobi no mono by the playwright and prominent Communist Murayama Tomoyoshi, since that’s what the film’s screenplay was based on. To my slight surprise, I found that the poison-thread thing isn’t in Murayama’s novel, and so must have been added during the transition from novel to screenplay. This suggested that in all likelihood the Goemon poison-thread story itself was no older than 1962, but the question remained as to where the poison-thread thing had come from in the first place.

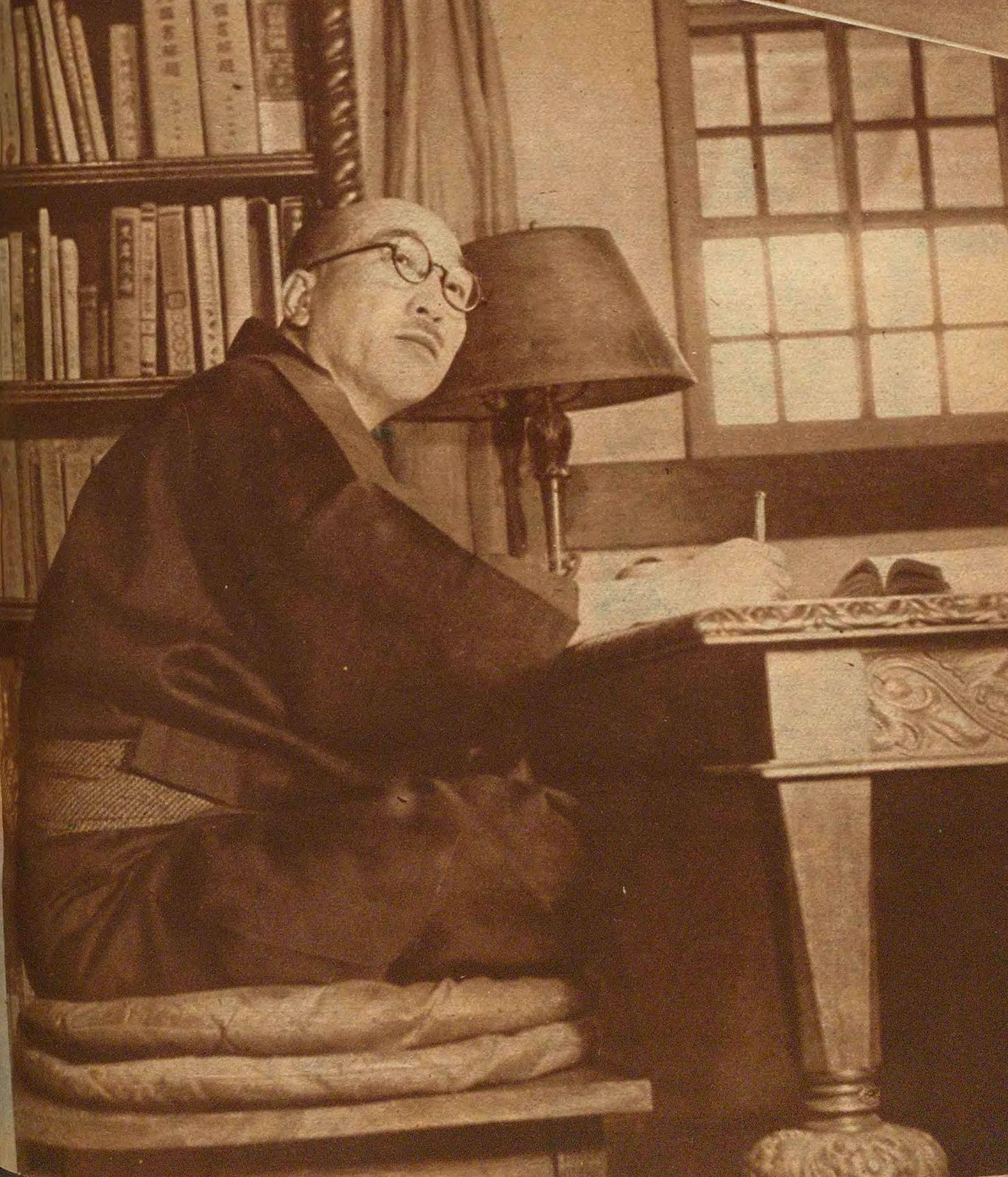

The answer, I realized, was that it had been taken from an earlier novel, The Stalker in the Attic (1925), by the Japanese mystery writer Edogawa Ranpo.4 Ranpo’s real name was Hirai Tarō; “Edogawa Ranpo” is a pen name, consciously intended to sound like a Japanized version of Edgar Allen Poe, whom Ranpo greatly admired.

The Stalker in the Attic, for the record, has nothing at all to do with ‘ninja.’ It’s a murder mystery set in prewar Japan, and the killer is an alienated loner named Gōda Saburō who, having nothing better to do with his time, takes to wandering around the open ceiling vaults of his lodgings and spying on the other inhabitants from above.5 Eventually, for reasons I won’t go into, he decides to murder one of the other lodgers. You can see the relevant moment in this 1986 anime version of the story, around the 11:30 mark:

The parallels with the climactic sequence of Shinobi no mono are striking, as you can see here if you wish to refresh your memory. The connection became even more iron-clad when I found that the screenwriter for Shinobi no mono, a guy named Takaiwa Hajime, was extremely familiar with Edogawa Ranpo’s work. In fact, Takaiwa had worked on a number of film adaptations of Edogawa Ranpo’s novels over the preceding fifteen years and met him in person on at least one occasion, in May of 1946, to discuss their collaboration.6

The Adventure of the Speckled Band → The Stalker in the Attic

So the connection seems pretty much undeniable: Goemon’s poison-thread thing isn’t an historical shinobi technique at all, but Takaiwa’s addition during the transition from novel to screenplay, borrowed from a novel by Takaiwa’s frequent collaborator Ranpo. In fact there’s probably yet another layer here, because Ranpo himself may well have taken the basic motif of poison-from-above from an even earlier source, the 1892 Sherlock Holmes story The Adventure of the Speckled Band. The Speckled Band is a classic ‘locked-room’ murder mystery, in which the victim is killed by the villain slipping a poisonous snake into the room through the hole in the ceiling used for the bell-pull.7 Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes mysteries were just as popular in Japan as they were elsewhere, and The Speckled Band had been translated into Japanese as early as 1899, so it’s almost certain that Ranpo was aware of it when he wrote The Stalker in the Attic in 1925. If he wasn’t then he definitely was four years later, because Ranpo published his own Japanese translation of The Speckled Band in an anthology of world detective fiction published in Japan in 1929.

What this means is that the claim that Ishikawa Goemon tried to kill Nobunaga by dripping poison down a thread is fiction from start to finish. It’s a scene from a 1962 movie, in turn inspired by a 1925 novel, which was itself borrowing from an 1892 Sherlock Holmes story.

I’ve made this point before, but I’ll make it again: everything I’ve laid about above is why I argue that the ‘ninja’ thing isn’t really an historical discourse, or at least not primarily so. It’s much better understood as a literary phenomenon, and once we grasp that point, figuring out why ‘ninja’ history works the way it does becomes much easier. This is also why you need literary scholars (like me) involved, just as much - or even more so - than conventional historians. Document-based historical study has basically nowhere to go when faced with claims like the Goemon poison-thread story; the only way to track them down and figure them out is to work with plays, novels, films, and the like, which are precisely what literary scholars know and are trained to handle.

Fictional though it might be, the poison-thread thing is undeniably cool, and it’s not surprising that it’s popped up in quite a few other venues in the decades since, most famously in You Only Live Twice. So, for the next post, I’d like to share some of the material I dug up concerning the poison-thread thing that didn’t make it into the published article, just by way of fleshing out the history of the motif and its subsequent circulation.

In case you’re wondering, this was probably the inspiration for the gruesome scene in the first episode of Hulu’s remake of Shogun, where a shipwrecked foreign sailor is boiled alive by the Japanese authorities.

Hey, I get to cite myself! Tuck, “The Fiction of the Ninja,” pp. 48-49.

The “Talk” page to the Wikipedia article is revealing; the bottom entry says:

“This article doesn't mention which story or stories are the source of the Goemon legends. All of the citations are for modern works. The earliest story mentioned in the article is the kabuki play from 1778. Surely the Goemon legend is older than that. Does anyone know which story is the original source of the Goemon legends? --49.192.183.210 (talk) 07:45, 28 March 2020 (UTC)”

Perhaps I should volunteer to edit the page.

The Stalker in the Attic (Yaneura no sanposha 屋根裏の散歩者); Edogawa Ranpo 江戸川乱歩 / Hirai Tarō 平井太郎 (1894-1965). “The Stalker in the Attic” is Seth Jacobowitz’s translation, and the story is available in his English translation if you’re interested.

Gōda Saburō 郷田三郎.

Takaiwa Hajime 高岩肇 (1910-2000). See Tuck, “The Fiction of the Ninja” Footnote #54, p. 72.

For this connection I have to give the credit to one of the anonymous reviewers for the article, who suggested that there might be a link between The Speckled Band and Ranpo.

Re: footnote 7, is there historical precedence for Reviewer #2 being actually helpful? 😂

I also now what sources to reference if I ever write a short story about an exasperated parent dripping a kale smoothie on a thread into a sleeping toddler’s mouth! (Prepared, naturally with an Ninja brand blender.)