Mis-Representation of Sources in Kacem Zoughari's "Ancient Shadow Warriors"

Zoughari's quotations aren't always what he says they are

Today’s post is the third part of my review of Dr. Kacem Zoughari’s 2010 book The Ninja: Ancient Shadow Warriors of Japan: The Secret History of Ninjutsu, published by Tuttle. My previous two posts documented what appears to be substantial plagiarism in the book’s second chapter, as well as an amazingly sloppy approach to the use of pictorial evidence. The third major problem and the one I want to address today is the book’s mis-representation of certain primary sources, which is arguably just as serious as the apparent plagiarism.

What is This and Why Does it Matter?

Mis-representation of sources is when you quote from or otherwise use a primary source document, but your presentation of that document’s content to the reader is inaccurate or misleading. As a very simple example, imagine that you’re writing a book about a guy called Bill Thomson, and you’re reading Bill’s diary for information about what he was doing on Wednesday. The diary says that Bill had spaghetti for lunch on Wednesday; you, however, then tell your reader that Bill had a sandwich for lunch that day. That’s not what the primary source says, and in telling your reader that Bill had a sandwich, you are mis-representing your source. Maybe it’s unintentional and you’re just sloppy in your note-taking. Maybe it’s fully intentional - you have an agenda to make sandwich-eating seem more common than it really was, or something - but either way, this is really, really bad.

The sandwich/spaghetti thing might seem like a pretty trivial example, but mis-representation is in fact a big honking deal in non-fiction writing. In a recent case that almost all of my academic readers will know about, a junior professor of Chinese history at Yale was accused of doing exactly this in a book she published in 2022, and the case got a ton of attention in large part because of how explosive that allegation is. Mis-representation of sources undermines the relationship of trust between writer and reader, because you can no longer be certain that the sources the author is quoting do in fact say what they appear to say. And if you can’t trust that the sources say what they appear to say, the underlying evidence, then you can’t trust the book, period.

Mis-Represented Source #1: Kōyō gunkan

Let’s dive straight in and explain what Zoughari’s Ancient Shadow Warriors does that’s so bad. Here’s our first example, found on p. 47:

The framing of this passage - “one finds the following in the chronicle Kōyō gunkan” and the indenting of the text, as is commonly done with longer quotes - leads the reader to believe that the text presented is a direct quote from the early 17th century military chronicle Kōyō gunkan (‘The Military Annals of Kai Province’).

This is not from Kōyō gunkan. There is no text matching Zoughari’s block quote in any edition of Kōyō gunkan that I have been able to access.

That much is obvious just by looking at the presented text itself; it’s incredibly unlikely that a 17th century Japanese writer would use phrases like “industrial exploitation” or “what one would call today an aptitude for mathematics.” These are very clearly 20th century phrasings, and my overwhelming suspicion is that the actual text being quoted in reality by a 20th century ‘ninja’ author.

So what is the actual source of the text presented, then? I don’t know. Normally, we would simply turn to the back of the book and check the corresponding end-note to citation #49. Unfortunately, Zoughari’s end-notes in this chapter are not properly aligned with the citations (editing issue, again), so it can be difficult to figure out which citation is meant to correspond to each source.1 Citation #49, as far as I can figure, should properly lead to endnote #50, which contains a description of Kōyō gunkan but - and this is the crucial point - no direct reference to any actual source text of the military chronicle. The only direct textual reference in end-note #50, as you’ll see, is in the last line, to historical novelist Tobe Shinjūrō’s Ninja and Ninjutsu, p. 110:

The thing is, I’ve checked Tobe’s book, and as far as I can see there’s nothing resembling the text Zoughari quotes on p. 110 or any of the nearby pages. So…there’s no way to confirm where the quoted text is actually from. The one thing we can say for sure is that the text is not what Zoughari claims it to be, as it’s not from either of the sources, Kōyō gunkan or Tobe Shinjūrō, mentioned in Zoughari’s endnote.

The discussion of citations is a bit nerdy, I admit, but the take-home point is this: Kōyō gunkan does not say what Zoughari tells the reader it does. I think what probably happened here is that Zoughari read this (rather weird) idea about ‘ninja’ being miners and metallurgists in some postwar author’s book, perhaps supported in that book with some vague reference to Kōyō gunkan. Possibly he intended to check Kōyō gunkan itself but never got around to it - that would explain the lack of any actual citation from Kōyō gunkan - and then got his notes so badly mixed up that he quoted the original secondary source by mistake.

That’s my best guess, because honestly Ancient Shadow Warriors is such a colossal mess that it’s very difficult to tell. For what it’s worth I suspect that the mis-representation wasn’t intentional; I don’t think Zoughari meant to mislead the reader. I think he’s just extremely careless and badly out of his depth in working with this much material in Japanese, so he can’t keep his sources straight and didn’t bother to check the primary text for himself. And while a competent editor might have caught some of these errors, all signs are that no such editor reviewed Ancient Shadow Warriors before publication.

Mis-Represented Source #2: The Taiheiki

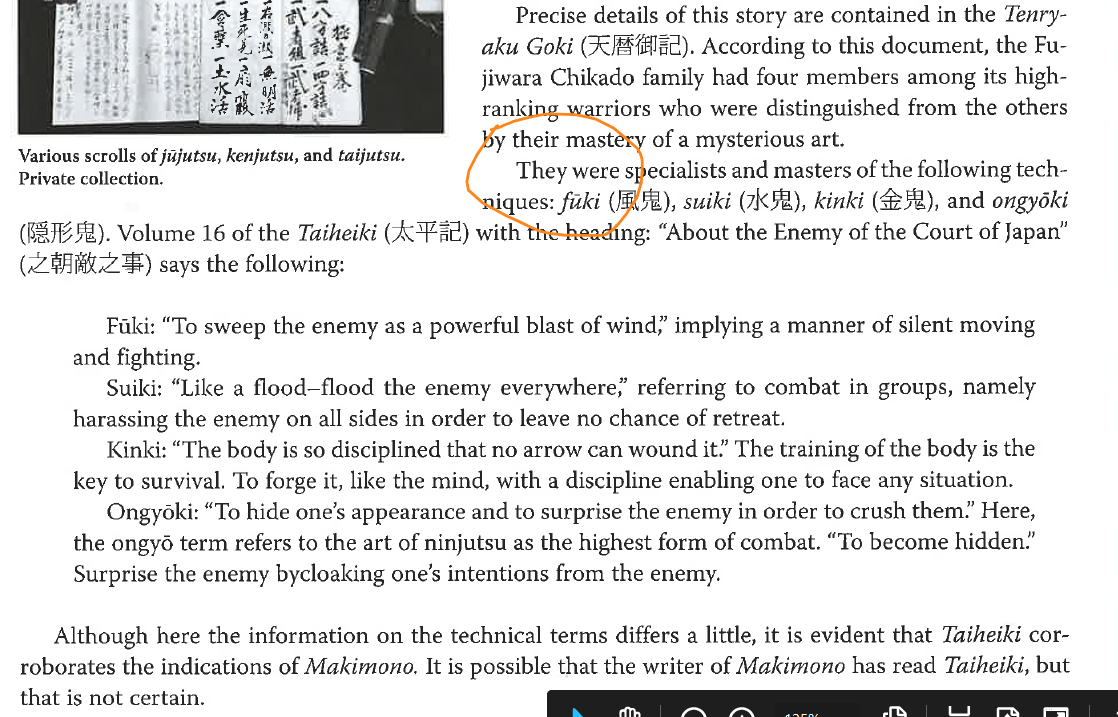

There’s another case of mis-representation in Chapter 3, “The Private History of Ninjutsu” (p. 78). It comes in the second paragraph, beginning “They were specialists”:

For context, Zoughari is discussing what he says are accounts of four “warriors” during the ancient period of Japanese history who were masters of “a mysterious art” - the implication being that these warriors were in fact early examples of ‘ninja.’

The point I’d like you to focus on is the central block quote. If you look directly above the block quote, you’ll see that Zoughari leads you to believe that this account of warrior techniques is from the Taiheiki (‘Chronicle of Great Peace’), a famous 14th century war chronicle we’ve discussed a few times in these pages.2

You may notice, if you’re really sharp-eyed, that Zoughari gives no citation to the Taiheiki itself. On checking the relevant section, it’s pretty clear why: the Taiheiki does not say what Zoughari says it does. The corresponding passage from Taiheiki actually says this (my translation):

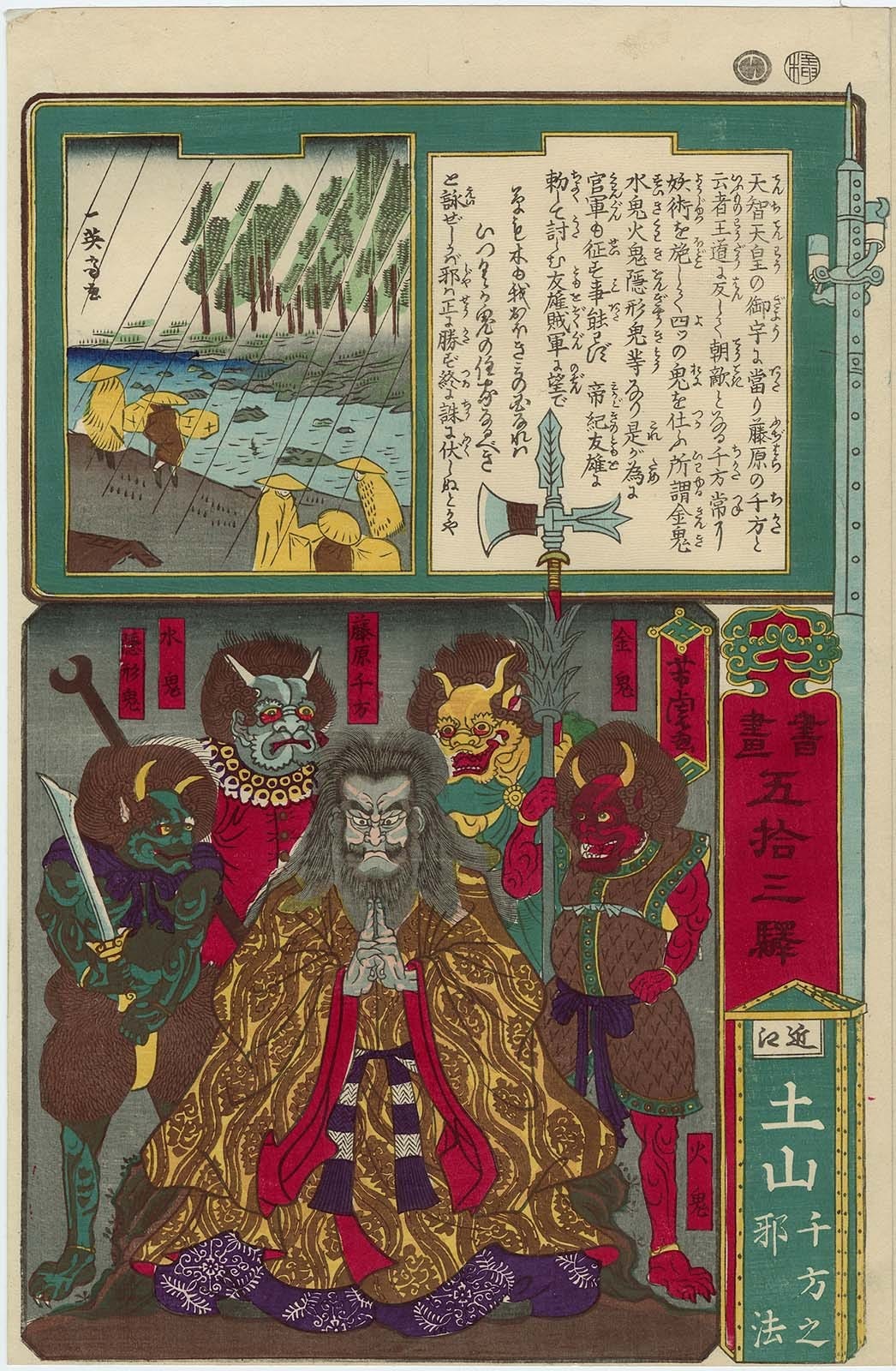

In the reign of the Emperor Tenji [668-671] there was a man named Fujiwara no Chikata, who employed four demons known as Metal Demon [Kinki], Wind Demon [Fūki], Water Demon [Suiki], and Hidden Demon [Ongyōki]. Metal Demon’s body was so tough that arrows fired at it did not penetrate. Wind Demon could summon up a great gale and blow down enemy fortresses. Water Demon could summon floods to inundate enemy bases. The Hidden Demon could become invisible [lit. hide his form] and suddenly grab the enemy.3

So Zoughari’s quoted passage and the actual text of Taiheiki do not match. The Taiheiki says that these were literal demons with supernatural powers; it does not say that they were mortal men with high-level military training. Note that subsequent interpretations of Chikata (not ‘Chikado,’ btw, as Zoughari has it) depicted him in exactly this way, as harnessing the powers of literal demons - as in the 1872 print that’s the splash image for today’s post.

So what is presented as a direct quote from a primary source is nothing of the sort. What Zoughari has given us is either his or someone else’s interpretation - a strained and dubious one, by the way - that this account actually refers to particularly skilled real-life warriors. The ‘they-weren’t-demons-they-were-really-ninja’ interpretation appears to be favored by modern ‘ninja’ historians, since the Iga Ninja Museum has it on their website. It strikes me as a very dubious reading of the text, rather like using Native American legends as evidence of Bigfoot, or claiming that the legend of Santa Claus must really have originated from a group of skilled yet generous burglars who wore red.

We could go round and round debating how far you can use fantastical legends to support historical claims. But that’s not the point I want to focus on here.

The point is that to lead your reader to believe that this modern ‘ninja’ writers’ interpretation of the Taiheiki is in fact what the Taiheiki actually says is inexcusably misleading. It would appear from the lack of any citation to the Taiheiki that Zoughari never bothered to check what the original text says, and simply assumed that the modern interpretation was close enough that it could be presented to his readers in place of the actual source. This, again, points more to incompetence rather than intent to mislead, but it’s still really bad.

And Possibly Others

As you can probably tell, I’ve gone through large parts of Ancient Shadow Warriors very carefully, checking a lot of the citations, and what I have found is dismaying in the extreme. A lot of Zoughari’s citations are incomplete or incorrect in some way, referring to a non-existent edition or publisher of a text, or simply not providing enough information to precisely locate the information being referred to. More worryingly, in somewhere between a third and half of the cases where the citation was complete enough for me to check, the source and page in question do not contain the information that’s supposed to be there. Despite the voluminous end-notes in Ancient Shadow Warriors, then, it’s often unclear what evidence actually underpins Dr. Zoughari’s claims, and I suspect that there may be more cases of mis-represented sources in the book. This is really pretty shocking when you think about it - Zoughari has a PhD from a solid academic institution, yet he doesn’t know how to cite properly? My first-year undergrads pick this up in a week or two, so what’s Zoughari’s excuse?

Given enough time I probably could identify most of these missing or incorrectly ID’d sources - I am, as you have seen, pretty good at this sort of thing - but this is not really a productive use of my time. It isn’t necessary to highlight every single last problem with Ancient Shadow Warriors to prosecute the case that the book is egregiously flawed as a work of history. I believe that I have made that case more than adequately through this and the previous two posts.

So what is to be done? To start with, we need to ask some serious questions of Tuttle Publishing as to how something this bad managed to not only make it past their review systems but to survive into a second edition. In the next post, then, I’ll wrap up the review and try to summarize what this fiasco means for the field of ‘ninja’ studies as a whole.

To get technical and nerdy here: It appears that Zoughari inserted a comment into the endnotes for Chapter 2 at #6 without adjusting the superscript citations in the rest of the chapter. The result is that every superscript citation after that, #7 to #89, is off by one; there isn’t actually a citation #89 to correspond to note #89. This should have been caught by an editor, but all the evidence suggests either that Tuttle made no attempt to edit the book before publication, or the editor was asleep at the wheel.

For what it’s worth, the graphs are wrong here, in yet another of the seemingly interminable sequence of minor errors. Zoughari has got the volume of the Taiheiki right but the Japanese graphs for the section wrong; the actual heading is 日本朝敵事 (‘Concerning Enemies of the Court of Japan’) not 之朝敵之事 (loosely translatable as ‘Concerning the Enemies of the Court of.’)