Tracking Down the Evidence for African Samurai's 'Ninja Assassination'

Where did Lockley and Girard get their lurid account of Yasuke killing a young 'ninja'?

As promised, it’s time for us to take an in-depth look at Lockley and Girard’s 2019 book African Samurai: The True Story of Yasuke, a Legendary Black Warrior in Feudal Japan.

Some of my readers will already be familiar with the controversy surrounding African Samurai just from generally being online. If you’re not, this past Monday I published a short piece at The Sundial, an online publication from the ASU Center for Renaissance and Medieval Studies, which should get you up to speed. The second half of the piece, Part 2, will follow next week, but there was a lot of detail I couldn’t fit into the second Sundial piece for reasons of space. So, this post and the next one will mostly consist of the stuff I couldn’t fit.

The TL:DR - Lockley and Girard have been doing some stuff they really shouldn’t have with their historical materials.

You Come at the King, You Best Not Miss

Probably the best place to start is by looking at one of the more exciting sections in African Samurai, which comes in chapter sixteen of the book. Titled “The Dead are Rising,” the bulk of the chapter tells of an assassination attempt on Oda Nobunaga, lord of the ‘African samurai’ Yasuke, while Nobunaga is traveling through Iga Province in central Japan. The would-be assassins are a group of ‘ninja,’ who open fire on Nobunaga with rifles and then close in to finish off the survivors in hand-to-hand combat. They’re able to get the drop on Yasuke’s party by hiding amid the bodies of the slain. Here’s how African Samurai tells it:

Suddenly the world exploded.

Where Nobunaga’s party had been there was now only smoke drifting in the frosty air. The pong of gunpowder filled the area, burned Yasuke’s eyes. The detonation had been more than gun-fire. Something else. An explosion like five cannon going off at the same time. But there’d been no cannon. Was this the ninja magic people spoke of? The snow was spattered crimson. Limbs of Oda soldiers lay scattered across the forest pathway. Dying men screamed.

And to add to the shock, the dead were rising.

Several Iga bodies between Yasuke and the black fog which now engulfed Nobunaga’s party, had stood. Tossing smoking large-bore guns, they drew their swords. Iga men who’d been hiding among the headless villagers. These were not the walking dead, they were ninja….

Yasuke swiped and missed one man who danced under a horse and onward. Another was not so lucky. Yasuke’s sword took him in the head, cleaving it in two. The Iga ninja, his grey clothing hardly visible in the smog, dropped in the churned, blood-splashed snow…

The Iga boy had been no match for Yasuke’s bulk and power, however much he feinted and twisted. He now lay at the African warrior’s feet, head severed and hanging from a few sinews of flesh. The smoke had now cleared to reveal the carnage hidden beneath. Interspersed by the dead ninja lay seven Oda clansmen.1

This has got everything a reader could wish for - a dramatic ‘ninja’ ambush, desperate hand-to-hand combat, and Yasuke getting a chance to prove himself a badass with some sweet katana moves.

If you’re a cynical bastard like me, though, your first thought is: Where are Lockley and Girard getting this stuff?

Primary Sources Optional

Tracing the exact sources that Lockley and Girard used in African Samurai is not easy. The book does not have precise source citations; instead, there’s a select bibliography of (mostly secondary) sources at the back of the book after each chapter. This is not particularly helpful, because there’s no page numbers given and no obvious indication as to which claim corresponds to which source. If you’re trying to check the evidence for a claim, you potentially have to search through maybe a dozen different books and articles to find the evidence you were looking for - assuming you have access to all of the relevant texts in the first place.

A non-fiction book being squirrelly about its sources is almost never a good sign, and unsurprisingly, it’s more or less standard practice in ‘ninja’ histories, which usually don’t have precise citations and are rarely explicit about the evidence for their claims. Though sometimes hand-waved by saying that ‘popular audiences don’t care about citations’ or something along those lines, my hunch is that this lack of interest in precise citation is mostly done for the convenience of the author. In other words, it’s basically laziness.

A more cynical view, of course, would be that omitting citations works brilliantly as a defense mechanism against serious scrutiny. After all, if nobody can tell what the evidence for your claim is, people’ll have to be very careful about challenging you, lest you whip out the missing evidence (AH-HA!) and prove them wrong. It also works as a hassle barrier, since it takes hours of work just to track down the likely source for one claim. Most academics won’t bother, because their time could more productively be spent writing a journal article or a book chapter.

Fortunately for you guys, I am not “most academics.”

Playing ‘Ninja’ Detective

There’s both a short and a long answer to the question of where Lockley and Girard got their account of the Iga ‘ninja’ ambush. The short answer, I’m fairly certain, is that their immediate source was Stephen Turnbull’s 2003 Ninja: AD 1460-1650, because that work appears a couple of times in African Samurai’s bibliography.2 The relevant passage in Turnbull’s book is as follows:

[T]he most remarkable assassination attempt on Nobunaga is recorded in the Iranki. Three ninja each took aim at Nobunaga with large-calibre firearms when he was inspecting the ruinous state of Iga Province that his invasion had brought about. The shots missed their target, but killed seven of Nobunaga’s companions.3

That’s the entirety of Turnbull’s discussion - three sentences. You may notice that there’s no mention of Yasuke being involved, of the melee that supposedly followed the opening shots, or of the detail that the ‘ninja’ hid among the bodies of the dead.4

So that’s the short answer as to where Lockley and Girard got the story: it came from Turnbull. The long answer, though, would be that the primary source is the text known as Iranki, as Turnbull himself notes.

The Iranki is a written account of Oda Nobunaga’s conquest of Iga Province during 1581. The text was probably compiled by an Iga scholar named Kikuoka Nyogen, who lived from 1625 to 1703.5 We don’t know exactly when it was written, though it’s reasonable to suppose it was during the last quarter of the 17th century (1675 to 1700), which would put the compilation of the history about a hundred years after the events it describes.

There are serious questions about the Iranki’s overall reliability, but let’s put those to one side and focus on what it says concerning the ambush.6 For what it’s worth, I think it’s very unlikely that Lockley and Girard read the Iranki itself. In fact, they’d probably be on firmer ground in terms of defending their approach if they admitted to not having read it, as we’ll see.

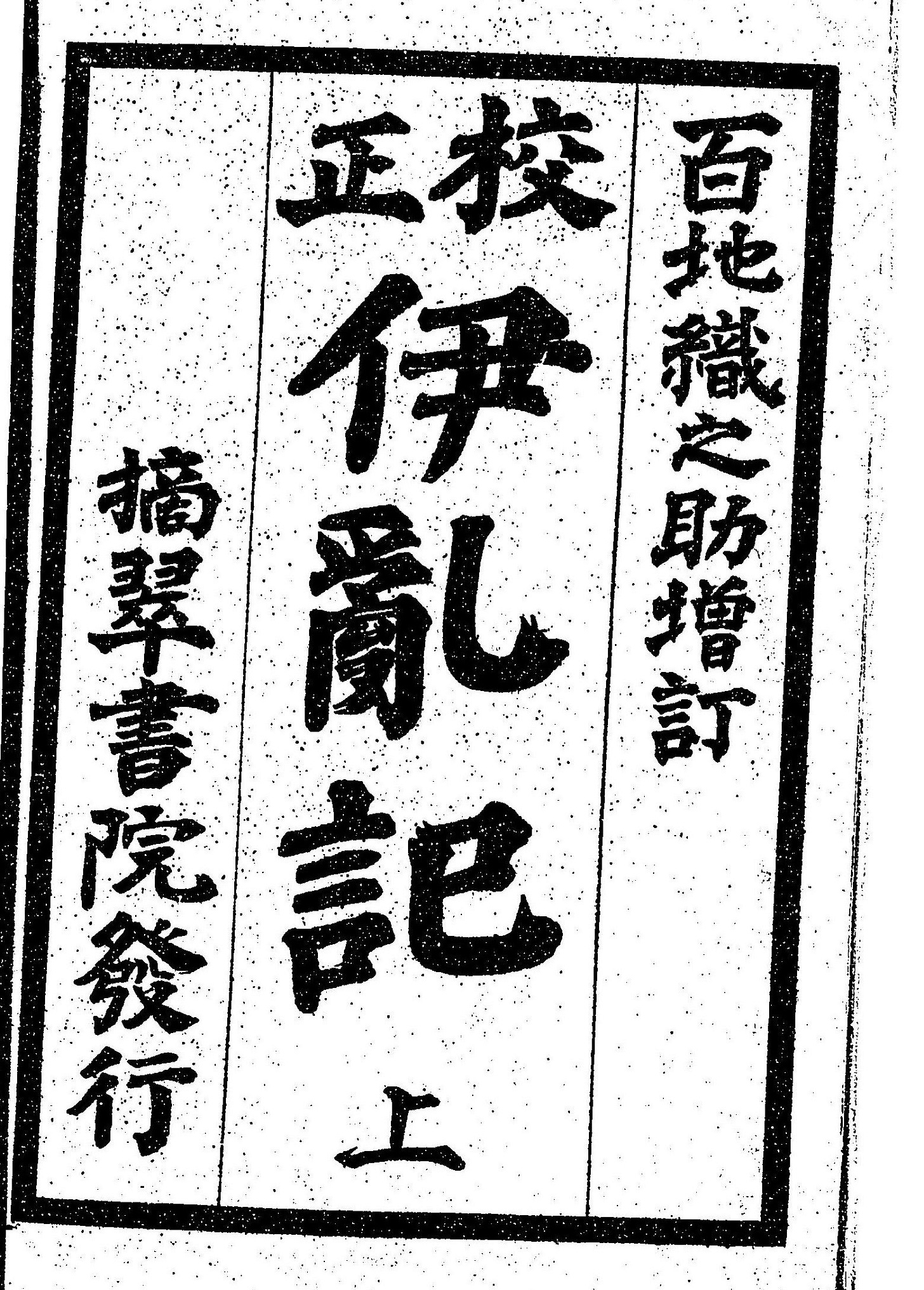

The relevant passage is not too long, so I’ll just translate it in its entirety. I’m using the 1897 edition of the Iranki available through the National Diet Library, if anyone wants to read it for themselves or check my work:

It was at this point that the three men Harada Mokuzō, resident of Tsuchihashi; the Magistrate of Ijiro, worthy man of the village of Ijiro; and Kido, resident of Otowa, made to shoot down Lord Nobunaga with large-bore firearms, as after the end of the fighting in Iga, Lord Nobunaga had come to the province to make a tour of the town of Ueno and was taking a moment to rest at Aekuni Shrine, the most important shrine of the province. Yet, perhaps because the cycles of Heaven were strongly in Nobunaga’s favor, though the three men lined up the barrels of their weapons and let fly with their shots, their aim was not true and they only succeeded in shooting down some seven or eight of Nobunaga’s closest attendants. The three men, having unexpectedly failed to kill their target, pointed toward [the village of] Otowa and fled like birds taking to the wing. Nobunaga’s men took up their bows and arrows and went after the attackers, but being uncertain of the terrain they could not strike the three men down.7

As far as I am aware, this source is basically it; there is no pre-modern source other than Iranki that describes this specific rifle ambush.

So what we’ve done here is to trace African Samurai’s rifle ambush episode back through two textual levels, first to Turnbull and then back to the primary source from which Turnbull himself derived the story. Ahead of the next post, I invite you to consider which parts of Lockley and Girard’s account are supported by the primary source evidence we have available, and which parts seemingly are not.

Lockley and Girard, African Samurai, pp. 232-233.

African Samurai’s bibliography doesn’t have page numbers, but Turnbull’s AD 1460-1650 is listed as a source for Chapters 5 and for Chapters 15 & 16.

Turnbull, Ninja: AD 1460-1650, pp. 32-33.

You might think: maybe these details are in one of Turnbull’s other books, perhaps his 1991 Secret Warrior Cult or his 2017 Unmasking the Myth? Nope. Both books do contain more detailed discussions of the Iga rifle ambush, Secret Warrior Cult on pp. 74-75 and Unmasking the Myth on pp. 70-71, but neither mentions Yasuke, melee combat, or the ‘ninja’ hiding among the dead.

Kikuoka Nyogen 菊岡如幻. His dates and the pronunciation of his personal name are per Nihon jinmei daijiten, accessed in online form through Japan Knowledge.

As Turnbull himself acknowledges in his 2017 Unmasking the Myth, p. 63. This is not just Turnbull; see e.g. Ikeda Hiroshi, who in an article otherwise fairly uncritical about the Iga shinobi acknowledges that “it is risky to cite Iranki without qualification as if it were historical fact” (史実的にそのまま引用すると危険である). Ikeda Hiroshi, “Iga Ninja hen” in Rekishi tokuhon vol. 49 no. 8 (August 2004), p. 56.

Momochi Orinosuke et al., eds., Iranki (Tekisui Shoin, 1897), volume 4 (fascicle 2), p. 5; corresponds to cell 60 in the NDL reader, on the left-hand side of the page.