(Quick housekeeping note: I’m going to be traveling for a little while at the beginning of October and won’t have access to my books, so I’m going to pause my posts for a couple of installments. I expect to resume the normal schedule on Tuesday October 15th).

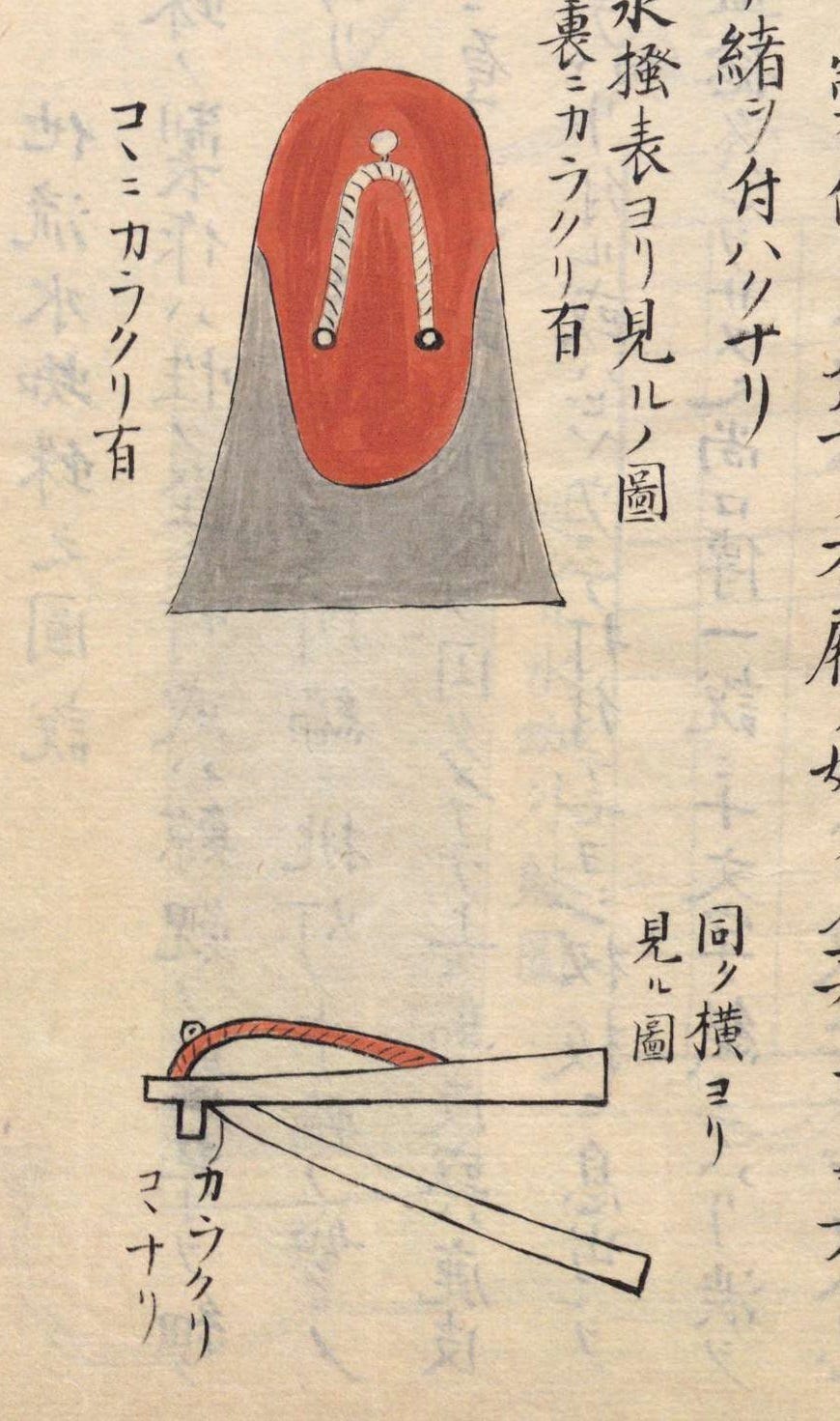

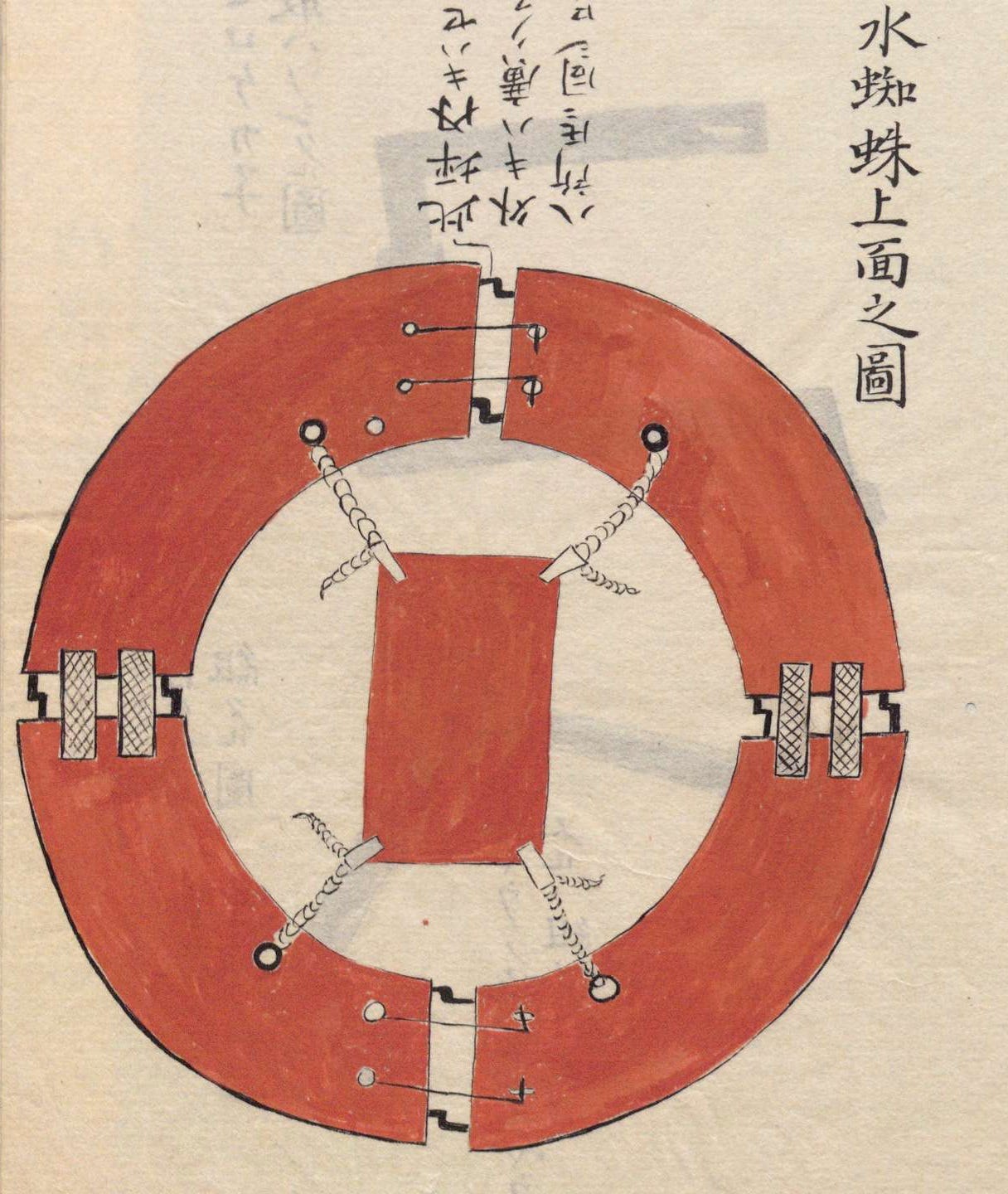

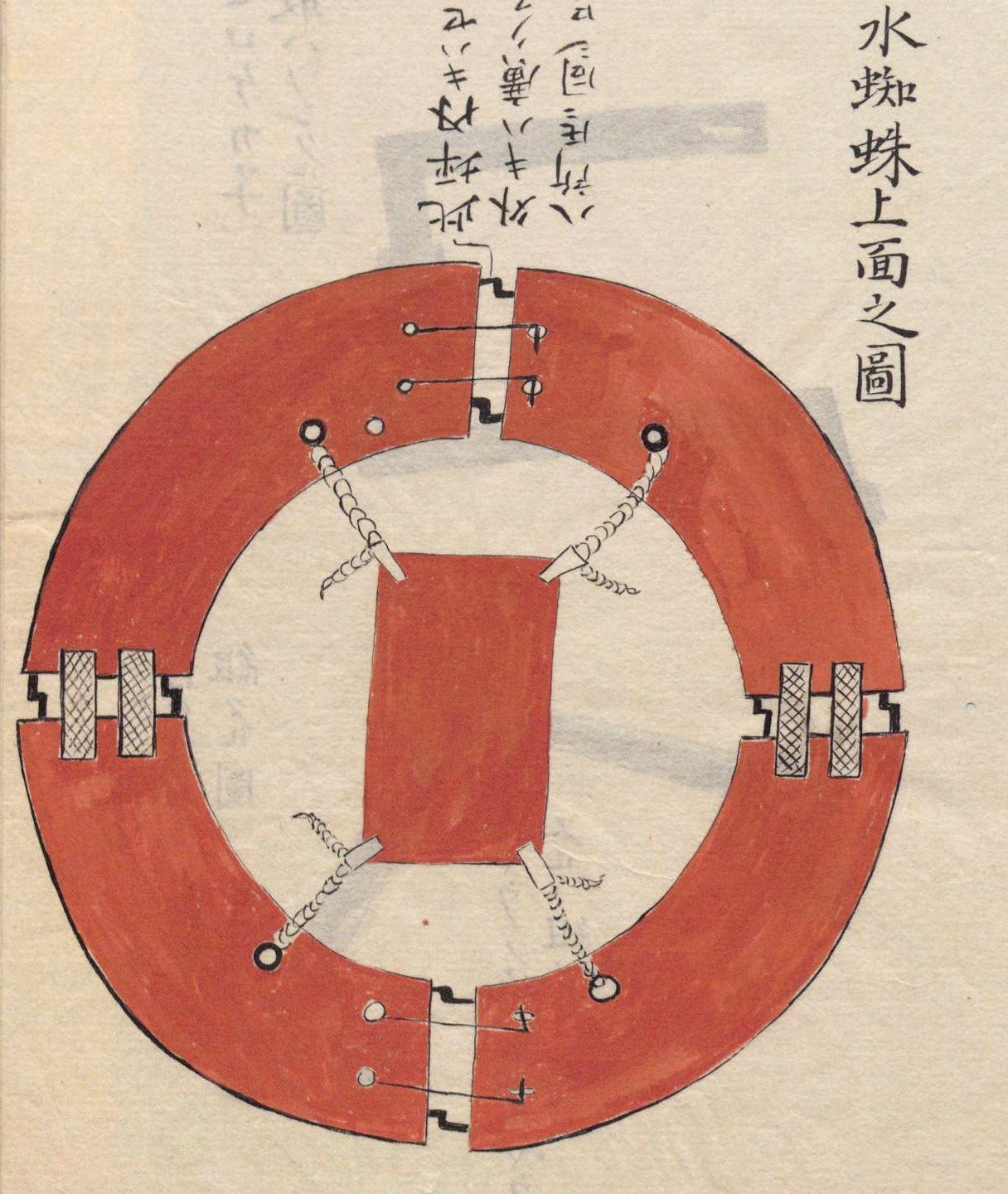

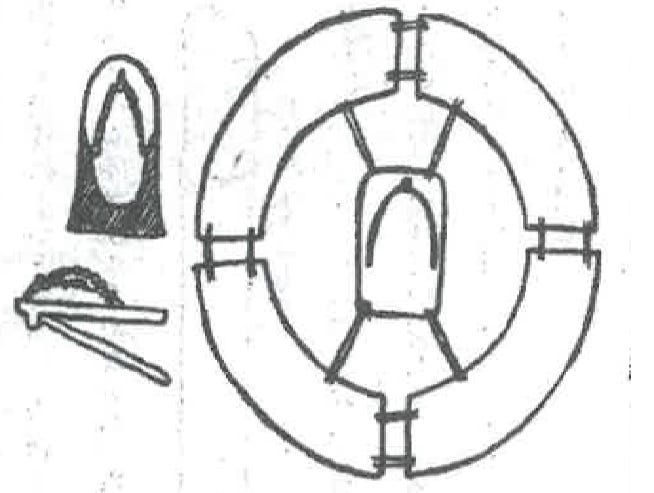

For those who aren’t already familiar, the above is a mizu-gumo, meaning literally ‘water-spider.’ It’s a device featured in the 1676 military manual Bansen shūkai, and it may well be the most famous ‘ninja’ tool of all, not least because it was the subject of a segment on the US TV show Mythbusters in 2007. Mythbusters described the device as allowing a ‘ninja’ to “walk on water,” supposedly by wearing one on each foot. They promptly found that it doesn’t work. At all. You sink, because the device doesn’t offer enough buoyancy or displacement to support the weight of an adult.

But here’s the thing - Bansen shūkai itself doesn’t actually say anything about “walking on water” - in fact, it doesn’t say anything at all about how the device is supposed to be used, beyond including it in the ‘water tools’ section. This leads most readers to suppose, reasonably enough, that the device was intended to be used in crossing wet things - rivers? lakes? swamps? castle moats? - but in the absence of any information as to how it was supposed to work, everyone is free to speculate (and boy, they have).

I’ve chosen to focus on the mizu-gumo thing here for a bit partly because it’s so well-known (and the subject of endless online debates), but also because the discussion surrounding it highlights a few endemic problems in ‘ninja’ ‘scholarship,’ making the discourse quite instructive. I think, also, I can offer a few perspectives on the device that seem obvious to me, but which are generally missing from the discussion as a whole.

So here’s my first point:

There’s No Reason To Believe This Was Ever Used

Almost all of the discussion surrounding the mizu-gumo takes it as read that the device was used by shinobi, and the only question is how. The thing is, though, I’ve seen no compelling evidence to support the contention that the mizu-gumo was ever used in the real world. As far as I know, we have no documentary evidence of its use, and no ‘ninja’ historian has ever given dates and places where the device is known to have been deployed. Debating how the mizu-gumo was used, then, seems pointless if we can’t show that it was.

This skipping over of a foundational question may remind you, incidentally, of our discussion on shuriken a few posts back. Debate about how shinobi used shuriken (to distract? dipped in poison? covered in horse dung?) is pretty widespread online and in various ‘ninja’ histories, as you may know. But debating how shinobi used shuriken is kind of pointless when there’s no evidence that they ever did (or, for that matter, that anyone else ever used star-shaped throwing weapons in anger). You might as well debate diseases of the hoof in unicorns.

Even leaving aside the lack of evidence for use of the mizu-gumo, the device seems at least partly at odds with what we know the historical shinobi did. Admittedly, we don’t know much, but a lot of the mentions of spies in Japanese historical texts suggest that they used disguise or subterfuge to gather information - a classic ruse was for a samurai to pretend to defect to another lord and enter his service, so that he could act as a double agent.1 The number of situations in which a shinobi would have needed to cross water - a river, a moat, a lake, or whatever - would probably have been very small, and most of the time there would have been no reason the shinobi couldn’t use a boat or simply swim.

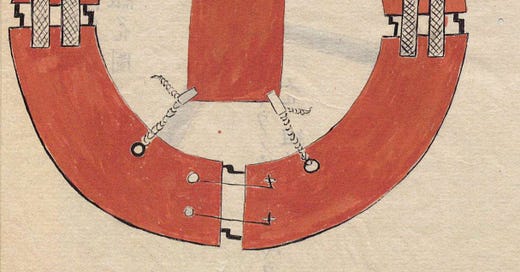

Funnily enough Okuse Heishichirō made this point in 1964, regarding these flippers (mizu-kaki) depicted in Bansen shūkai:

Of these, Okuse writes:

These are supposedly used to swim faster, but I don’t know about that. It doesn’t seem to me that a ninja would need to know how to swim.2

As I mentioned in the previous post, Okuse was - somewhat surprisingly - openly skeptical about the BSSK’s ‘water tools’ and the mizu-gumo in particular. In his 1964 Ninja Techniques: Secret Teachings and Real Examples, he writes:

Mizu-gumo. Made of wood, circular. A folding buoy. One puts one foot on the board in the middle and wears two of them, and supposedly walks on the top of the water; but even if you lined the device with leather or oiled it, the best it could offer would be 2 kg of buoyancy, so it would be impossible for a 50-60kg human placed on top of it to float. The idea is very striking, though.3

The thing is, though, that there’s an image above Okuse’s discussion of the mizu-gumo which appears to be from the Iga-Ueno Ninja Museum, of which he was a founding director. It shows a pair of mizu-gumo along with a plaque that does indeed describe them as “a device for walking on water” (suijō hokōki).4

So it would appear that the idea that the mizu-gumo allowed you to walk on water was out there by at least 1964. It may in fact have been out there even earlier, since in an article in the English-language Japan Magazine from 1957 we have a picture of an unmistakable mizu-gumo with the caption:

A portable water-ski, with the aid of which a ninja is said to have walked on water. 5

Note the qualifier “is said to” - a notable hedge, but one that a casual reader could easily miss.

At least some of the people making assertions about the mizu-gumo in the late 1950s and early 1960s, then, clearly hadn’t tested the device or even thought very seriously about the physics behind its use. We know for a fact that you can’t walk on water using this device - Mythbusters proved that, and Okuse had pointed it out as early as 1964.

This brings me to my second main point:

Nobody Really Knows Anything About This Thing

Much of ‘ninja’ history is about perceived personal authority rather than historical evidence, unfortunately. ‘Ninja’ historians therefore love to make authoritative statements about how the mizu-gumo was actually a flotation device worn around the hips rather than a pair of shoes; or that it was a specialty of shinobi from the Koka region; or that it was actually used to cross mud flats, rice-fields, or marshes rather than deep water, and so on and so on.6

As far as I can tell, little to none of this is based on historical evidence, testing of the device, or on reasoning from known physical principles. So when you hear talking heads on YouTube or wherever confidently assert that ACTUALLY the mizu-gumo was such-and-such, keep in mind that everything they’re saying is basically a guess - they don’t know this for sure.

This point is nowhere better illustrated than with Fujita Seiko. Seiko, as we’ve seen, was one of the main pre-war figures advocating for ninjutsu as being a method of spycraft and physical training (the other was Itō Gingetsu), and his work would later be picked up and developed by figures such as Okuse and Hatsumi Masaaki from the late 1950s onward.7

BSSK itself appears to have been unknown in Japan until the 1930s, and Seiko, who apparently owned a manuscript copy, was one of the people who first publicized it. The mizu-gumo is one of the most striking images in the whole of BSSK, so it’s not surprising that Seiko’s 1938 book What is Ninjutsu? features a reproduction of the device, as well as the flippers from BSSK:

There are a couple of things worth noting here. One is the presence of a strap on the central board of the device, presumably to allow it to be worn in the manner of traditional Japanese footwear such as geta. You’ll notice, if you now look at the original drawing of the device in the BSSK, that the BSSK doesn’t include a strap, so that bit must have been Seiko’s addition:

The caption to Seiko’s rendering is also worth remarking upon, because while the mizu-gumo isn’t mentioned by name, it’s part of a set described as “devices for walking in water.” Note the preposition “in,” not “on,” because the Japanese caption says suichū o aruku, which probably means walking through water (i.e., immersed in it) rather than walking on water (i.e., on top of it, which as we saw above would be suijō).8 What’s more, Seiko’s picture accompanies a discussion about ‘ninja’ swimming and movement in water, so it’s not necessarily clear-cut that Seiko was the one who argued that you could use it to walk on water, at least not in 1938.

(This leads me to wonder when the claim of walking on water was first made. I don’t have an immediate answer to that, though based on the above it must have been some time between 1938 and 1957.)

What we can say, though, is that Seiko’s addition of the strap to the device is clear evidence he thought it was to be worn on the feet. Possibly he thought it was kind of a flipper device to be worn while immersed in water, but since Seiko doesn’t say anything specific in the pages of What is Ninjutsu?, we’re left to guess. If that was indeed what Seiko thought, it’s hard to imagine he had actually tested it or thought very carefully about its use. I can’t see the mizu-gumo working as a flipper, since for one thing, it’s way too big, and for another it has large openings in it, which would allow water to pass through it instead of pushing against it. Effective flipper designs tend to be solid, flat shapes with a little bit of give to them, whether we’re talking about a duck’s webbed feet or a set of diver’s flippers.

My read? I don’t think Seiko had any privileged knowledge about the device at all and was simply guessing. But surely (I hear you cry), surely a fourteenth generation master of Koka-style ninjutsu - as Seiko claimed to be - would know all the greatest secrets of the shinobi? If Stephen Turnbull is to be believed, the device was a specialty of Koka-style ninjutsu, after all, so if anyone would know about the mizu-gumo, he would?

Yeah. Apparently not. Maybe the thirteenth-gen Grand Master forgot to tell him. Or maybe Seiko was out that day. Perhaps he was throwing up after eating rat poison (which he claims to have done in What is Ninjutsu?), or maybe he was horrifically hungover after drinking a near-lethal dose of alcohol (which he also claims to have done in the same book).9

My point, then, is that despite his claims to be a NINJA GRAND MASTER, Seiko seems to have been largely in the dark about the mizu-gumo device, the same as everyone else.

Making a Splash

The way that ‘ninja’ claims usually developed in 20th century Japan was that Itō Gingetsu or Fujita Seiko first aired them between about 1910 and 1940, and Okuse Heishichirō, Hatsumi Masaaki, and all the rest of them then further embellished and publicized those claims after the war, catching the attention of a much broader audience. That’s not quite what happened here, though, because as we see Seiko obviously didn’t know how the device was supposed to be used, while Okuse thought that it couldn’t ever have been used in the first place. So too, in fact, did Hatsumi; in his 1964 kids’ book Ninja and Ninja Skills Illustrated he presents the mizu-gumo as a device for walking on water, as we’ve seen, but adds:

This device often shows up in ninja stories, but it would be very difficult to walk on water using this mizu-gumo. Some people argue that it is doubtful whether or not the ninja of old really crossed water using this.10

So we have an interesting situation here, whereby almost none of the major Japanese ‘ninja’ writers to 1964 or so had actually claimed that the mizu-gumo device really would allow you to walk on water or endorsed that idea. As far as I can see, it was only the Iga-Ueno museum that had made this claim, though there’s clearly further research to be done here.

It was pretty obvious early on, then, that the mizu-gumo wouldn’t work as a device for walking on water. What followed, and what’s arguably the more interesting element of the story, was a series of attempts to make it work - to find a way in which the device shown in BSSK, or at least something roughly resembling it, could allow someone to float in or move through water.

That’s the topic for the next couple of posts. These will be a bit delayed, since as noted above I’m going to be traveling for a bit and will have to pick up when I get back. Keep your powder dry, everyone.

No need to ‘sneak in’ if you can gain entry by deception. This happened at least twice that I know of; during the 1540s, the Uesugi clan sent two men named Honma and Inomata to spy on the Later Hōjō by pretending to pledge their service to a branch clan of the Hōjō. In the second case, in 1547 the warlord Matsudaira Tadatomo 松平忠倫 (?-1547) was assassinated by a warrior named Kakei Shigetada 筧重忠 (?-1588) who had gained entry by pretending to pledge his service. See Kōbunsha, ed., Nihon gaishi vol. 10 p. 439 (Kōbunsha, 1914) and vol. 18 p. 103 (Kōbunsha, 1926).

Okuse, Ninpō: sono hiden to jitsurei, 1964, pp. 258-9. Japanese: 早く泳ぐためだというが、どんなものだろうか。忍者に競泳は必要なさそうに思うが。

Okuse, Ninpō, p. 257. Japanese: 《水蜘蛛》木製、円型。折畳式のブイである。真中の板に片足をのせ、二つをはいて、水上を歩行するとあるが、皮を貼っても、油をぬっても、せいぜい二キロ位の浮力しかないから、五十~六十キロの人間をのせて水上に浮ぶことは、不可能である。但しアイデアは奇抜で面白い。

50-60 kg (110-130 lbs) might seem low for an adult, but Japanese people of the Warring States period are known to have been significantly smaller than their modern counterparts (less meat and very little calcium in the diet, for one), so it’s probably about right.

Japanese: 水上歩行器.

Anon, “Ninja: The Japanese Supermen” Japan Magazine 1957, p. 26.

Cummins argues that the mizu-gumo was actually a flotation device in Minami, trans., The Book of Ninja pp. 328-331, and the translation describes it as a “water-seat,” though the BSSK original doesn’t say this. Turnbull states that the mizu-gumo was a specialty of Koka ‘ninja’ in Ninja: AD 1460-1650, p. 62, while the claim that mizu-gumo were used on marshland was made on Mythbusters, as well as here, here, and probably loads of other places as well.

A quick note - why am I referring to Okuse Heishichirō by his surname, but Fujita Seiko by his first name? The reason is that Seiko was Fujita’s pen-name, and the standard convention in Japanese studies is to refer to someone by their pen-name if they have one. So the novelist Natsume Sōseki (real name Natsume Kinnosuke) is universally Sōseki, while the novelist Tanizaki Jun’ichirō, who wrote under his real name, is Tanizaki. The more you know…

The caption says suichū o aruku ni mochiuru dōgu 水中をあるくに用ふる道具, or ‘tools used to walk in water.’

Yes, he claimed to have done both. See Fujita Seiko, Ninjutsu to wa nani ka - the rat poison is on p. 78 original/63 translation and the alcohol thing on p. 75 original/61 translation.

Seiko claimed to have drunk a bit more than eight shō (approx. 14.4 liters, or about 30 US pints) of sake in a period of four hours. For reference, Japanese sake generally has an alcohol content of between 12 and 15%, so assuming 12% alcohol content that would be about 3.6 pints/2045 ml of pure alcohol over a period of four hours. I’m no doctor, but that seems pretty close to a lethal dose for most adults.

The rat-poison claim is sufficiently bizarre that Eric Shahan, the translator, felt compelled to add a very helpful note reminding readers not to eat rat poison. Good to see someone looking out for the health of ‘ninja’ enthusiasts.

As you may have guessed, my view of Seiko is that he was an attention-seeking fabulist, and it’s beyond me why anyone takes his historical claims seriously, but there you are.

Hatsumi, Ninja, ninpō gahō (first pub. 1964), p. 69. Japanese: 忍者ものには、よく登場するが、この水グモをはいて、水上を歩くのは、ずい分むずかしい。昔の忍者がほんどうに、これを使って水の上を渡ったかどうかが、疑わしいという説もある。